Source: The Conversation – UK – By Rachel Delman, Heritage Partnerships Coordinator, University of Oxford

Hawks are taking cinematic flight. In two recent literary adaptations, they are entwined with the lives and emotions of their respective protagonists – Agnes Shakespeare (née Hathaway) and Helen Macdonald.

Birds of prey and their symbolism are explored in Hamnet, Chloé Zhao’s adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, and H is for Hawk, based on Macdonald’s 2014 memoir. In these films, hawks become complex and multifaceted figures, articulating gendered relationships to grief, nature, humanity and selfhood.

Hamnet is set in the Elizabethan period, and H is for Hawk in the modern day. However, the relationship between women and birds of prey has an even longer history. My research shows that in the medieval period, too, that relationship was multilayered. Far more than fashionable accessories, hawks offered women both real and symbolic means to express gender, power and status within a male-dominated world.

The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC

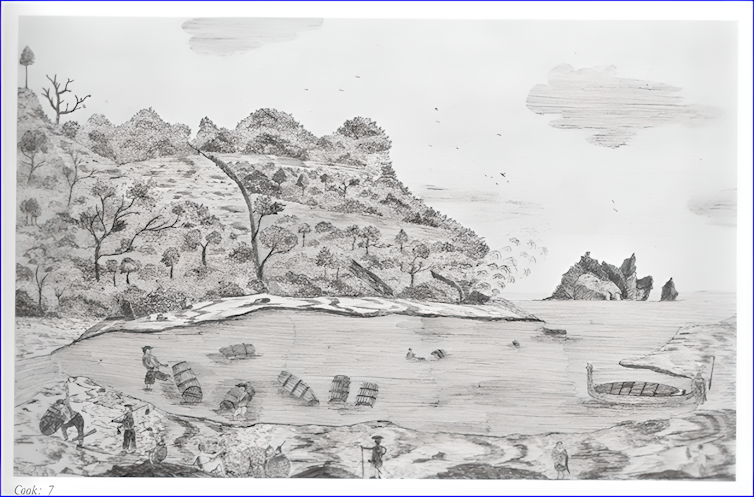

In the middle ages, the process of training hawks, with its delicate dance of control and release, was popularly associated with the game of courtship between men and women.

Falconry’s romantic connotations are emphasised in art, objects and literature from the time. Images of men and women hunting together with birds of prey feature across a wide range of medieval material culture, from tapestries for castle walls to decorative cases used to contain and protect hand-held mirrors.

The largest of four fifteenth-century tapestries, known collectively as the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, takes falconry as its subject. Lovers are depicted strolling arm-in-arm as their birds hunt prey.

On a smaller scale, two fourteenth-century mirror cases from the collections of the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art show scenes of lovers riding on horseback, each holding falcons. The mirrors may have been gifted as love tokens. Literary texts are also filled with references to women with, and even as, hawks.

The trope of the woman as a hawk needing to be tamed and controlled, however, was not a straightforward one of female submission. Falconry and its symbolism offered elite medieval women mastery and autonomy.

Defining themselves

Where high-status medieval women had the opportunity to represent themselves through visual culture, they often chose to include birds of prey. This is most obviously seen in seals, which were used by a wide range of medieval people to authenticate legally binding documents. Seals represented the sealer’s endorsement, identity and status.

The iconography of seals, and the matrices or moulds used to create them, provides important evidence of how women of status wished to be perceived and remembered. Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, the youngest daughter of King Edward I and Eleanor of Castile, chose the most popular motif among 13th-century women as the matrix for her personal (privy) seal. It shows a woman standing upright, her body tilted towards an obedient bird of prey in her left hand.

In another seal-matrix from the same century, Elizabeth, Lady of Sevorc is shown in a more energetic pose. She rides side-saddle, a falcon in one hand and a large eagle’s claw in the other.

Through their seals, medieval women showed their mastery over their birds of prey and affairs, and their belonging to a fashionable and powerful female collective.

British Library

Beyond imagery, records show that queens and noblewomen created and managed parks and hunting grounds. They also hawked together, trained birds of prey, and even gave them as gifts.

Smaller birds, such as merlins, were considered appropriate for women. In the film adaption of H is for Hawk, Claire Foy’s Helen refuses to settle for a merlin, dismissing it as a “lady’s bird”. It seems that medieval women similarly refused to be limited by the options conduct manuals offered them.

Henry VIII’s paternal grandmother, Margaret Beaufort, had many birds of prey. These included merlins and lannerets as well as larger species such as goshawks and lanners.

The deer park Beaufort created at her palace at Collyweston in Northamptonshire, with its terraces, ponds and water meadows, was ideally suited to falconry. Her daughter-in-law, Queen Elizabeth of York, who had her own room at the palace, hunted with goshawks.

In some cases, women appear to have been recognised as authorities on falconry-related matters. The Taymouth Hours, an illuminated 14th century book likely produced for a queenly reader, shows women with billowing headdresses hunting mallards with large birds of prey. The women adopt authoritative stances, demonstrating their skill, command and control over the birds.

In the following century, Dame Juliana de Berners, a prioress from Sopwell Priory, is thought to have authored at least part of the Boke of St Albans, which contains treatises on hunting and hawking.

British Library

Research by English Heritage has identified that women could even make a living from their expertise in training hawks. In the mid-13th century, a woman named Ymayna was the keeper of the Earl of Richmond’s hawks and hounds at Richmond Castle. In exchange for her expertise, she and her family were permitted to hold land nearby.

Ymayna stands out as a woman in a male-dominated profession, but her example suggests that there were probably other women like her, whose names are unidentified or absent from the historical record.

Women falconers may have been among the owners and users of knives, the handles of which survive in museum collections across Europe. An exquisitely carved example from the 14th century, now displayed in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, takes the form of a noble lady with a tiny bird of prey clutched close to her heart.

Literary texts reveal that falconry offered opportunities for female socialisation and bonding. In the Middle English poem Sir Orfeo, Orfeo spies a collective of 60 women on horseback, each with a hawk in hand.

British Library

In Hamnet, Agnes tells her husband William Shakespeare that her falconry glove was a gift from her mother. Medieval and early-modern women certainly gave gifts to one another, including gloves. My research, however, suggests that birds of prey were more commonly gifted between women and men.

Margaret Beaufort gave and received birds of prey to and from male relatives and associates, including her young grandson, the future Henry VIII. Birds of prey were considered suitable gifts for special occasions and life milestones. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, gave her nephew, Henry Courtenay, three falcons to mark his elevation to the title of Marquess of Exeter in 1525.

That powerful women landowners participated in rituals of gift exchange with men suggests falconry was not a straightforwardly feminine expression of power and status. Through their ownership of parks and the giving and receiving of birds of prey as gifts, women also used the culture of falconry to show their belonging to a masculine world of hunting and lordly largesse.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

![]()

Rachel Delman received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (2013-2016) and the Leverhulme Trust (2019-2022).

– ref. Medieval women used falconry to subvert gender norms – https://theconversation.com/medieval-women-used-falconry-to-subvert-gender-norms-274374