Source: The Conversation – UK – By Claire O’Callaghan, Senior Lecturer in English, Loughborough University

Wuthering Heights initially baffled readers who dismissed it as “a strange book”.

Earlier readers found it was “wild” and “confused”, portraying a “semi-savage love”. Yet, in 1850, the poet and critic Sydney Dobell recognised its originality and power, praising the novel’s distinctly poetic quality. To Dobell, “the thinking out” of many of the passages was “the masterpiece of a poet, rather than the hybrid creation of a novelist”.

Fittingly, before Heathcliff and Cathy haunted the moors, Emily Brontë was crafting her magic in verse preoccupied with death, steeped in grief and brimming with elemental passion and the spectral. Such motifs form the beating heart and singular atmosphere of Wuthering Heights, but without her gothic poetry, her beloved novel may not have existed. And, while this novel defines her reputation today, in her lifetime she was first and foremost a poet.

Among all her poems, Remembrance (1845) stands out as a direct ancestor of Wuthering Heights. The speaker mourns a lover lost for “15 wild Decembers”. It is full of imagery of frozen graves and icy bodies “cold in the earth” foreshadowing Cathy’s burial. The snow also anticipates the wintry desolation that frames Wuthering Heights.

In Written in Aspin Castle (1842-43), Lord Alfred’s spectral roaming in his family home (Aspin Castle) is not unlike the return of ghostly little Cathy to her childhood home in Wuthering Heights. In fact, Aspin’s “spectral windows” anticipate the window on which Mr Lockwood’s sleep is disturbed by what he assumes is a branch knocking on it.

“I must stop it, nevertheless!” I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch: instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand!

Windows as gothic portals clearly fascinated Emily, a fascination vividly captured in a drawing she produced in 1828 at just ten years old.

And in The Prisoner (A Fragment) (1845-46), the captive heroine – also like Mr Lockwood in Wuthering Heights – is tormented by nightly visitations in her “dungeon crypt” where a spiritual messenger figured as the wind summons “visions” that “kill me with desire”, which is much like Heathcliff’s anguish.

Cold in the earth

It is, however, Remembrance’s central question if “time’s all-severing wave” has broken their bond that directly foreshadows Cathy’s haunting challenge to Heathcliff: “Will you forget me – will you be happy when I am in the earth?” Cathy torments Heathcliff at length on this point, asking if “20 years hence” he will say, “that’s the grave of Catherine Earnshaw. I loved her long ago, and was wretched to lose her; but it is past.”

Yet, while the poem’s speaker finds a way to live alongside the painful memory of love lost, Heathcliff cannot adapt. Death for him is a psychological catastrophe, and he remains trapped in grief, unable to exist “without [his] life” – Cathy.

Remembrance was born in the imaginative world of Gondal, a poetic fantasy realm that Emily created with her sister Anne in childhood and continued to write about through adulthood. Set on an island in the North Pacific, Gondal was a landscape of political intrigue and destructive passions ruled by formidable women, such as the enigmatic A.G.A. – a figure deeply bound to the forces of nature, much like Heathcliff.

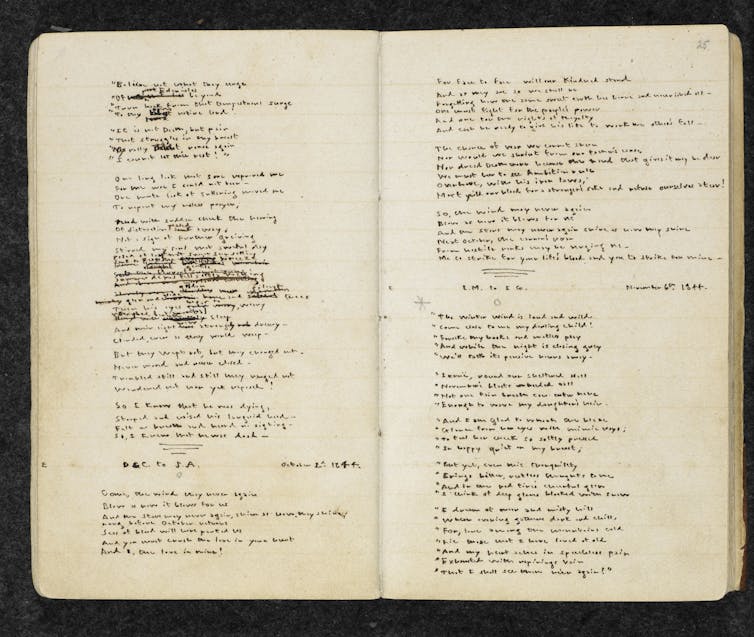

Gondal’s terrain gave Emily the freedom to explore the themes that later erupt in Wuthering Heights. And long before being revised for publication as Remembrance in 1846, the first iteration can be seen in a poem set in Gondal written in 1845. The speaker in this earlier work is the female character R. Alcona who is addressing her dead lover, Julius Brenzaida. Only fragments of Emily’s Gondal saga survive, but R. Alcona is thought to be Rosina of Alcona, a powerful figure, and Julius the Prince (later emperor) of Gondal.

Wikimedia

In another poem addressing Rosina as his “despot queen”, Julius casts Rosina as the tyrant of his soul. Blaming her for his spiritual imprisonment, he laments being ensnared by her “haughty beauty”, finding her eyes “shine/But not with such fond fire as mine”. The anguish and accusation he directs at Rosina echo the tortured reproach of Heathcliff to Cathy in Wuthering Heights, especially when he tells Cathy that she has shattered her own heart “and in breaking it, you have broken mine”.

Secret notebooks

Emily’s poetic journey began in secret. Her sister, Charlotte Brontë wrote in the Biography of Ellis and Acton Bell of how in 1845, she “accidentally alighted” on a private notebook of verse in her sister’s hand. What she discovered astonished her: these were “not common effusions”, she reflected, but poems that possessed “a peculiar music” – “wild, melancholy, and elevating”.

Though Emily was furious at the intrusion on her privacy, Charlotte insisted the poems deserved a readership. From that fraught moment came a plan for joint publication, and in 1846, Emily published 21 poems in a joint collection with her sisters. Writing under the nom de plume “Ellis Bell”, the volume Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell sold only two copies, according to Charlotte, on its first printing.

A few perceptive critics, however, singled out the “spirit” of Emily’s verse, sensing an extraordinary poetic “power” that might one day “reach heights not here attempted”. While Poems brought neither riches nor security, it achieved something else: it paved the way for the sisters to produce and publish their now canonical novels a year later – Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre.

Wuthering Heights stands apart from other Victorian novels precisely because it was crafted by a poet who never ceased thinking in verse. Its windswept moors, restless spirits, and love that defies death were first imagined in poetry, where snow falls endlessly over the “cold earth” and love endures beyond the grave. This poetic apprenticeship laid the foundation for Emily Brontë’s timeless gothic novel that continues to captivate hearts and minds worldwide.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Claire O’Callaghan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How Wuthering Heights was shaped by Emily Brontë’s gothic poetry – https://theconversation.com/how-wuthering-heights-was-shaped-by-emily-brontes-gothic-poetry-275948