Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Nicholas Marcelli, PhD Candidate in English Literature and Creative Writing, Queen’s University, Ontario

In an age of inequality and exploitation, a 1906 novel that exposed hazardous working conditions and unsanitary practices in Chicago’s meat-packing plants at the turn of the 20th century still pops up in discussions about unjust labour.

A 2025 Current Affairs story about health problems for workers in poultry and pork processing plants reported on by the U.S. Department of Agriculture suggests “we never left Upton Sinclair’s Jungle”.

A 2024 book, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry explains how the Department of Labor’s discovery, in 2022, that “a contractor hired … to clean slaughterhouses employed over a hundred children in ‘hazardous occupations’ seems as if it came “straight out of ‘The Jungle.’”

What is it about Upton Sinclair’s 120-year-old novel that endures?

Read more:

Radicals in the Democratic Party, from Upton Sinclair to Bernie Sanders

Novel’s origins

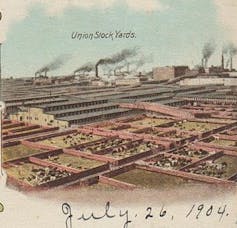

In 1904, Sinclair was commissioned by an editor of the socialist newspaper the Appeal to Reason to write a novel about wage slavery. Sinclair reveals in his autobiography that he chose the Chicago stockyards as its setting because of a recent failed strike led by the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America.

Beginning in October 1904, Sinclair lived for seven weeks among those he described as the “wage slaves of the Beef Trust” and went undercover in the plants by posing as an employee. He began writing on Christmas Day 1904, and three months later, the book was complete.

The Jungle appeared serially in the Appeal to Reason from February to November 1905 before being published as a full-length novel by Doubleday, Page & Co. in February 1906.

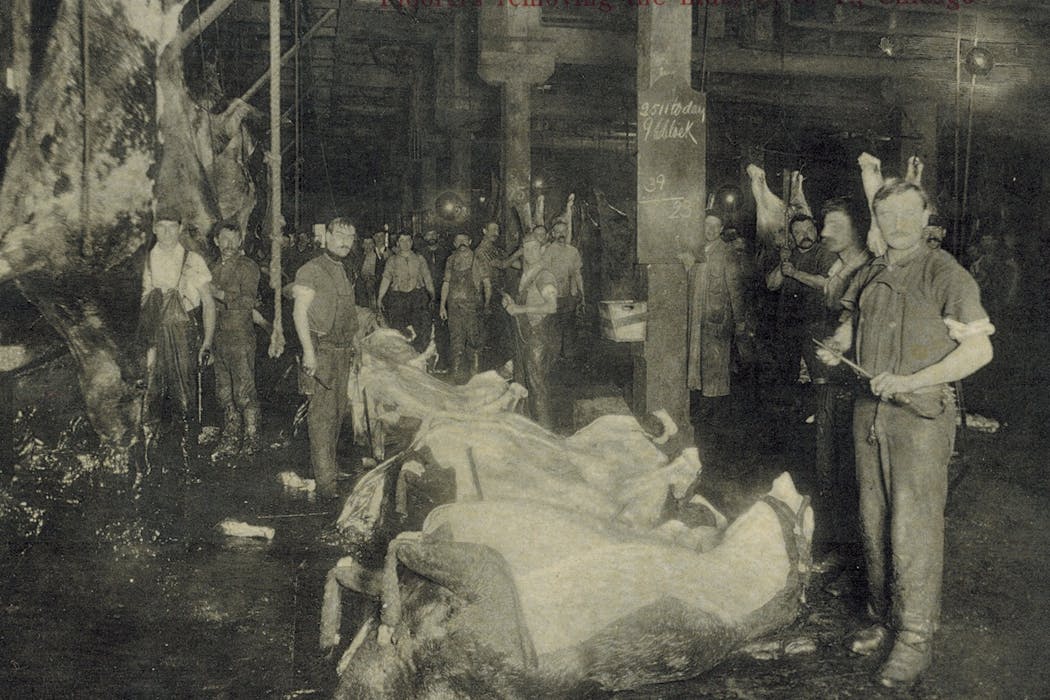

Harrowing conditions

(Jason Woodhouse/Flickr), CC BY

The book tells the story of Jurgis Rudkus, who is drawn to the stockyards by the promise of wealth after immigrating with his family from Lithuania to Chicago’s Packingtown neighbourhood. When family members, including the children, find work in the plants, they experience harrowing conditions.

As tragedy befalls them, the novel becomes a condemnation of early 20th-century capitalism, ultimately celebrating the virtues of socialism.

Although Sinclair’s novel is not without its flaws — for example, an unnamed critic in the March 3, 1906 edition of The New York Times wrote Sinclair’s “art is too obvious, his devices too trite” and “there is nothing spontaneous in the book save his imaginative descriptions of human misery” — the book portrayed vivid scenes.

Notably, The Jungle depicted child labourers, primarily Stanislovas Lukoszaite, a 14-year-old member of the family who is sent to work in a lard-canning factory.

Novel’s reception

While The Jungle was a novel, it simultaneously continues to be regarded as one of the most significant pieces of muckraking journalism —

pre-First World War writing concerned with exposing hardships or corruption and promoting social and political reform.

In journalism historian Bruce J. Evensen’s book, Journalism and the American Experience, he describes how Sinclair had hoped that when the novel was published, “it would expose the deplorable working conditions of killing and cutting gangs. Instead, it was his frightful description of food processing that provoked public outrage.”

This misplaced attention famously led Sinclair to declare in his autobiography: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

All but one of Sinclair’s claims were proven true in a special investigation into the Chicago stockyards conducted in June 1906 at the request of President Theodore Roosevelt. Investigators confirmed the unsanitary working conditions in the meat-packing plants, but made no reference to child labourers.

In author Jack London’s review of The Jungle for Wilshire’s Magazine, he called the book “the ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ of wage slavery,” a reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, first serialized in an abolitionist newspaper.

Read more:

How ‘Uncle Tom’ still impacts racial politics

London described how Sinclair “painted a horrifying picture of the industry, which still haunts the American imagination.”

Depictions of child labourers

(Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection/Wikimedia), CC BY

I contend that the endurance of The Jungle in the current popular imagination stems from its representation of children’s work in the meat-packing industry, particularly at a time, as Sinclair writes in the novel, when packers “worked all but the babies.”

Children were seen as essential because, as described by a character in the novel, Grandmother Majauszkiene, “there was always some new machine, by which the packers could get as much work out of a child as they had been able to get out of a man, and for a third of the pay.”

When Sinclair was writing, there may have been anywhere between 700 and 1,600 children under 16 years old working in the plants. Economist Edith Abbott, drawing from the 1905 Census of Manufacturers, writes that out of 74,134 employees nationwide, 974, or two per cent, were children.

Scant statistics around working children

In my doctoral research, I have found there are few statistics on the number of children working in meat-packing plants during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, either due to the lack of reporting or efforts by employers and families to avoid child labour laws. This view is reaffirmed by Sinclair’s contemporary, Algie Martin Simons, in his 1906 pamphlet, “Packingtown.”

(Wikimedia)

Because of the scant statistics and lack of accurate reporting or testimony from child workers in the meatpacking plants of the early 20th century, The Jungle, as a literary work, is an important piece of evidence that children worked in these plants at all.

Today, advocacy groups like the Economic Policy Institute and The Child Labor Coalition and journalists who include Alice Driver and Hannah Dreier have been documenting the ongoing, simultaneous rise in child labour law violations. There has been a decrease in labour law protections — not just in meatpacking and agriculture, but in industries throughout the U.S.

The continuous necessity of reporting on child labour law violations reaffirms the view that we never left The Jungle.

‘The Jungle’ continues to resonate

Ultimately, while The Jungle has maintained a 120-year legacy as a buzzword for child labour and exploitative labour practices more broadly — in addition to its exposé of early 20th century meatpacking — my interest in the text stems from Sinclair’s work as author and mediator who represents exploitative labour to the public.

How does he, as someone who only lived in Packingtown for seven weeks, portray the workers and the community they belong to, or depict the abuse of workers? What issues are raised around fact-based reporting and fictionalization?

The same questions, of course, are relevant for all reporting and narratives, especially about exploited and marginalized groups.

![]()

Nicholas Marcelli has received an Ontario Graduate Scholarship from Queen’s University and the Province of Ontario to fund his doctoral research.

– ref. ‘The Jungle’ at 120: How a 1906 novel continues to surface in discussions about unjust labour – https://theconversation.com/the-jungle-at-120-how-a-1906-novel-continues-to-surface-in-discussions-about-unjust-labour-265234