Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Susan H. Kamei, Adjunct Professor of History and Affiliated Faculty, USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Cultures, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

With a stroke of a presidential pen, the lives of Izumi Taniguchi, Minoru Tajii, Homei Iseyama and Peggy Yorita irreparably changed on Feb. 19, 1942. On that day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which set in motion their wartime incarceration along with other people of Japanese ancestry who were forcibly removed from their homes in parts of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona.

To cope with their fear, anger and loss in the turbulent times, they would have to dig deep into their emotional reservoirs of resolve and ingenuity.

Without bringing charges against them or providing any evidence of disloyalty, the U.S. government detained legal Japanese immigrants and their American-born descendants in desolate inland locations during and after World War II, simply because of their ethnicity. Nearly 127,000 people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated between 1942 and 1947, according to Duncan Ryȗken Williams, director of The Irei Project, which is compiling a comprehensive list of those detained. My grandparents, parents and their families were among them.

As I describe in my book “When Can We Go Back to America? Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II,” they boarded livestock trucks and World War I-era trains guarded by armed U.S. soldiers for destinations that were not disclosed to them. They could only take what they could carry and what they had within themselves.

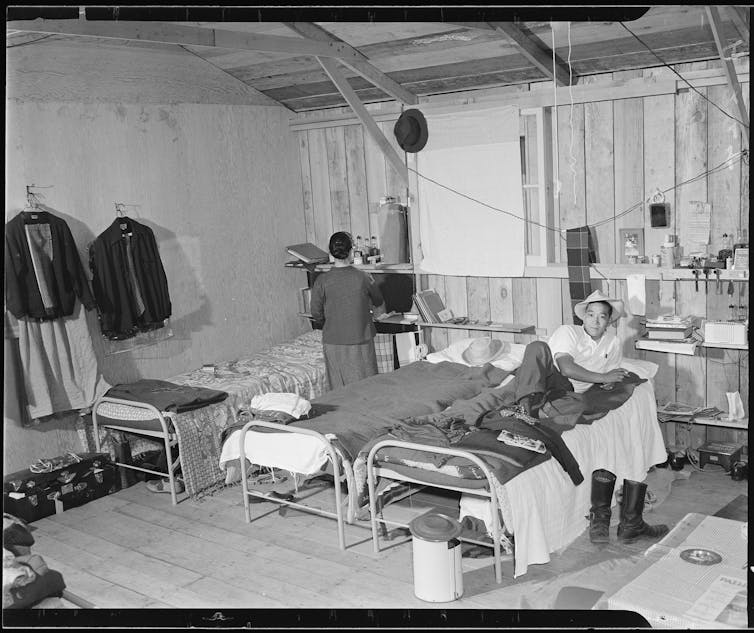

When the Japanese Americans arrived at temporary detention facilities, euphemistically called “assembly centers,” hastily constructed on fairgrounds, racetracks and other government property, they were shocked to be body-searched, fingerprinted and interrogated. Thousands discovered their living quarters were animal pens or horse stalls. The ones considered lucky were assigned to poorly built barracks. The barracks had only cots, bare light bulbs hanging from the ceilings, and pot belly stoves in the corners; the interiors lacked any partitions.

Clem Albers, War Relocation Authority, Department of the Interior via National Archives and Records Administration

Immediately they scavenged wood from vegetable crates and construction debris they found nearby to create privacy within the barracks units and to make furniture and other household furnishings. Displaced from their livelihoods, education and social structure, with nothing to do, they also quickly organized a wide range of activities, including sports, as well as arts and crafts of all kinds. Their resourcefulness born out of necessity converged with the Japanese aesthetic to make functional items beautiful as they sought to make their temporary quarters more livable.

When the prisoners were transferred to long-term detention facilities run by the War Relocation Authority later in 1942, they brought with them what Delphine Hirasuna, an author and descendant of people who had been incarcerated during the war, calls the “art of gaman.” “Gaman” is a Japanese word meaning the dignity and grace to bear the seemingly unbearable. With this philosophy, they created objects of both utility and beauty.

Finding beauty in branches, rocks and shells

At the Gila River and Poston camps located on tribal land in the Mojave Desert, incarcerees found that desert wood could be carved, filed and polished to make partitions, household objects and works of art.

Armed soldiers guarded the barbed-wire perimeters from lookout towers, but as the war wore on, the incarcerees were allowed to venture beyond the camp fences. Izumi Taniguchi, then 16 years old from Contra Costa County, California, recalled getting permission to walk outside the Gila River camp boundaries to while away the time.

He remembered, that some people used the ironwood for sculpting. Minoru Tajii, then 18 years old from El Centro, California, held at the Poston camp, described ironwood as “an oil-rich wood, so when you polish it up it comes out very nice, so we go out and find that and bring it back.”

The Poston “sculptoring department” advertised in the camp newsletter “Poston Chronicle” on Jan. 20, 1943, that “anyone with ironwood wishing to learn how to make figures and notions may bring their materials to the department, 44-13-D, and work under the guidance of sculptoring teachers.”

Gift of the artist’s family via Smithsonian American Art Museum

Homei Iseyama, from Oakland, California, became known for the exquisite teapots, teacups, candy dishes and calligraphy inkwells he carved out of slate stones he found around the Topaz, Utah, camp. Born in 1890, he attended Waseda University in Tokyo before immigrating to the United States in 1914 with dreams of attending art school.

At the Tule Lake camp, located on an ancient lake bed, the incarcerees discovered thick veins of shells that provided material for making art and jewelry. Fusako “Peggy” Nishimura Yorita got very involved in making shell jewelry. As digging for shells became a popular and competitive pastime for the Tule Lake incarcerees, Yorita enlisted her two teenagers and friends to help dig waist-deep holes at sunrise and sift the sand with homemade wire sieves.

Courtesy of the Bain Family Collection via Densho Digital Repository

A 33-year-old single mother, Yorita sold her shell jewelry to make a little money. She also enjoyed the creative endeavor. She recalled: “I was just making new things all the time. And to me, it … was … a wonderful outlet.”

As the incarcerees were allowed to leave the camps, they were given $25 and a one-way bus or train ticket to wherever they were going to rebuild their lives. Many took with them their handcrafted objects, reminders of how they overcame the physical and mental harshness of their detention years.

Courtesy Susan H. Kamei, CC BY-NC-ND

When my mother entrusted to me the fragile small tansu chest that her father made for her in camp out of crate wood, she told me that her father had felt sorry for her that she didn’t have anyplace to store her belongings. To improve the appearance of the wood, my grandfather placed a hotplate on the pieces to deepen the grain. My mother appreciated the care he took to carve traditional Japanese scenes onto the panels with a pen knife. She said the chest represented to her the depth of her father’s love.

Eight decades after Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, researchers are delving into the traumatic intergenerational impact that the incarceration has had on the camp survivors and their descendants. Memorials such as The Irei Project seek to restore dignity to those who suffered unconstitutional injustices. On Feb. 19, known annually as the Day of Remembrance, Americans can honor them by appreciating their “art of gaman,” testaments to their resilient spirit as they found and created beauty in their wartime environments.

![]()

The Mellon Foundation has provided funding to the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, which is one of Susan Kamei’s academic affiliations. Duncan Ryuken Williams is the director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. She is a researcher for The Irei Project and is a member and volunteer of the Japanese American National Museum.

– ref. Held captive in their own country during World War II, Japanese Americans used nature to cope with their unjustified imprisonment – https://theconversation.com/held-captive-in-their-own-country-during-world-war-ii-japanese-americans-used-nature-to-cope-with-their-unjustified-imprisonment-272989