Source: The Conversation – UK – By Paul van Hooft, Research Leader, Defence and Security, RAND Europe

The New Start nuclear arms control treaty expires on February 4, opening up the way for a period of great power uncertainty and the possibility of a new arms race.

The US-Russian agreement, negotiated in 2010 and extended in 2021, limited the number of deployed nuclear warheads to 1,550, with roughly 3,500 non-deployed warheads in reserve. It was the last of the arms control agreements that were rooted in the legacy of the cold war negotiations between the US and the Soviet Union, and the era of relative optimism that followed it.

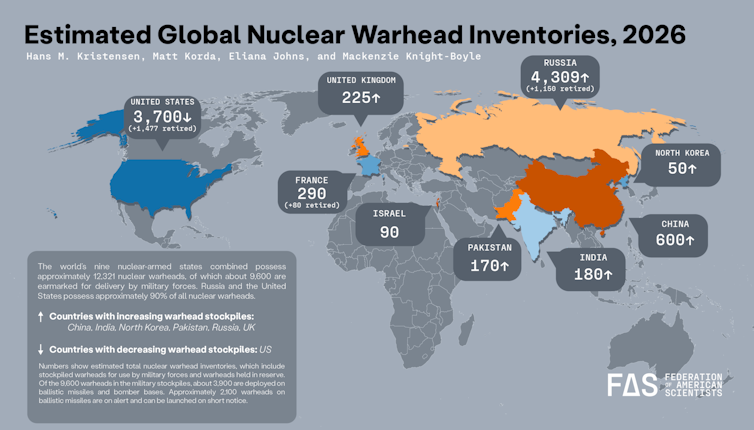

The current US administration has shown little appetite for extending Start on a purely bilateral basis, as it hopes to include China in any new agreement. China’s nuclear arsenal has more than doubled in size in the past five years to an estimated 600 warheads with the expectations of further increases over the next decade.

The emphasis on China is not recent. Even before the latest Trump administration took office in January 2025, a 2023 bipartisan committee concluded that the US nuclear force posture was insufficient for a modern “Two Peer Plus” environment. Two Peer Plus means the US needs to be able to jointly confront two major nuclear-armed powers – Russia and China – while having the capacity to face threats from other lesser adversaries, mainly North Korea.

The Trump administration would prefer a treaty that would address this new reality. However, Chinese officials are reluctant to discuss joining such an agreement. They argue their arsenal is still far smaller than that of either the US or Russia and that it is unfair to ask China to restrain itself.

Allowing New Start to lapse is a negative signal but it is unlikely to immediately trigger a cold war–style arms race. Washington and Moscow seem more confident in their assured second-strike capabilities than they were then, with fewer concerns about a disarming first strike. And, no matter the rhetoric, both will probably want to avoid rocking the boat too much or too soon.

More likely is that the US will invest in further modernising its delivery systems to improve accuracy against mobile targets and penetration against hardened Russian bases and missile silos.

Russia, meanwhile, has recently displayed some exotic new delivery systems, including the Poseidon nuclear torpedo and the Burevestnik nuclear cruise missile.

But it is unclear whether the country could produce these systems at a scale to make a difference. Or even whether such systems truly change anything about the overall US-Russia calculus, given the large numbers of land- and submarine-based ballistic missiles that Russia already has.

Russia may therefore be incentivised to deploy more warheads with existing missile systems This would be faster and cheaper than developing and producing new delivery methods.

End of the peace dividend?

Perhaps more importantly, the consequences of New Start’s expiration extend far beyond gradual shifts in nuclear force posture. Its demise marks the collapse of yet another pillar of the post–cold war international order. With the end of the intermediate nuclear forces (INF) treaty in 2019, the conventional force in Europe treaty in 2023, and others, the arms control architecture is already on its last legs,

The demise of the INF treaty was also partly triggered by Sino-American competition. The US wanted to be less restrained in the Indo-Pacific, where China had built a formidable arsenal of short- and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles.

The broader system of negotiations and institutionalised diplomatic exchanges is equally important. They facilitated understanding of the other’s interests and red lines, not out of sympathy but to allow states to manage the inherent uncertainty and mistrust present in strategic competition.

Federation of American Scientists

The decline of this kind of diplomacy may not have immediately noticeable effects on international security, but it makes misperceptions and misjudgements during peacetime and during crises likelier. Personalised diplomacy is ill suited to managing long-term rivalry between nuclear-armed states. They are less likely to address deeper structural conflicts of interest or build deep knowledge of the other side.

Even if New Start were extended once more, it would not resolve the underlying structural challenges. China’s unlikely participation remains a central obstacle. So does the broader Two Peer Plus problem, where the US perceives the risks of Russia and China together.

At the same time, US strategic priorities have shifted. The Trump administration’s new national security strategy and national defense strategy made clear that Europe and Russia are no longer central concerns, eclipsed by the western hemisphere and the Indo-Pacific.

Read more:

What the US national security strategy tells us about how Trump views the world

Where does this leave Europe?

Europe has limited leverage to prevent the drift away from arms control. French and British nuclear forces are deliberately small and geared toward existential deterrence, leaving little scope for negotiated reductions. If anything, given the growing pressures on these states to take a greater role in European deterrence, the incentive is to expand their nuclear options, not to limit themselves.

Over the long term, Europe’s most viable path may therefore be to first invest significantly in conventional capabilities to generate pressure on Russia and then to consider building up the existing European nuclear arsenals. Such an asymmetric approach to arms control would be difficult. It would depend on Russia reaching exhaustion in its war on Ukraine, leaving it unable and unwilling to compete with both the US and Europe.

The end of New Start will leave the strategic environment more uncertain and thus more dangerous for everyone. It would not trigger an immediate arms race, but it would further erode the norms, transparency and institutionalised dialogue that have helped manage nuclear competition for decades.

It may well further incentivise non-nuclear states to reconsider their non-proliferation commitments, already under pressure due to the uncertainty surrounding the US security guarantees. In a more multipolar nuclear world marked by mistrust, technological rivalry and diverging priorities, deterrence without arms control becomes more brittle, not more stable.

![]()

Paul van Hooft receives funding from RAND Europe to work on deterrence and arms control related issues.

– ref. New Start’s expiration will make the world less safe – even if it doesn’t spark another nuclear arms race – https://theconversation.com/new-starts-expiration-will-make-the-world-less-safe-even-if-it-doesnt-spark-another-nuclear-arms-race-275116