Source: The Conversation – UK – By Lucy Hart, PhD Candidate, Environmental Science, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University

When the phaseout of ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) was first agreed in 1987, the world narrowly avoided an environmental catastrophe. However, the replacement of CFCs is causing the pollution of the Earth’s surface with a “forever chemical” that could remain in the environment for centuries.

The chemical trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is a breakdown product of numerous chemicals, including CFC replacement gases used in refrigeration and air conditioning, pharmaceuticals such as gases used in inhalation anaesthesia, pesticides, solvents and other forever chemicals from a class known as per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Concentrations of TFA have been increasing in rainwater, drinking water, soil and plants over the past two decades. Environmental removal of any of the thousands of different PFAS chemicals is extremely challenging because existing removal technology is difficult to scale up.

If emissions aren’t restricted, the projected cost of PFAS removal has been estimated at €100 billion (£86 billion) per year for Europe. Some researchers have labelled TFA as a “planetary boundary threat” which means it could disrupt Earth’s natural systems beyond repair and threaten our survival.

While some PFAS have been linked to numerous cancers and fertility problems, the long-term health effects of TFA on humans and wildlife remains unknown. However, it has been detected in human blood, breast milk and urine, and is being considered for classification as toxic to reproduction by German government agencies.

While understanding of its consequences continues to develop, increasing TFA pollution urgently needs to be addressed.

Read more:

The last ozone-layer damaging chemicals to be phased out are finally falling in the atmosphere

A better understanding of the many TFA sources and their relative contributions to environmental levels is required to inform targeted policy.

Evidence from ice cores can offer clues to help detangle these sources. TFA concentrations in Arctic ice over recent decades match the their increasing use. In 2020, Canadian researchers hypothesised that some CFC replacement gases which are known to break down to produce TFA in the atmosphere could be a major source.

These CFC replacements – known as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) – are commonly used in refrigeration, air conditioning and for making insulating foams. They eventually leak into the atmosphere as gases and can travel vast distances. These CFC replacements break down to form TFA and other gases. TFA can be either dissolved in clouds then washed out of the atmosphere through rain or deposited directly from air onto the Earth’s surface.

Our new study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, quantified the contribution of these CFC replacements and also inhalation anaesthetics to global TFA production. We found that one-third of a million tonnes of TFA (335,500 tonnes) has been deposited to the Earth’s surface from these sources between 2000 and 2022.

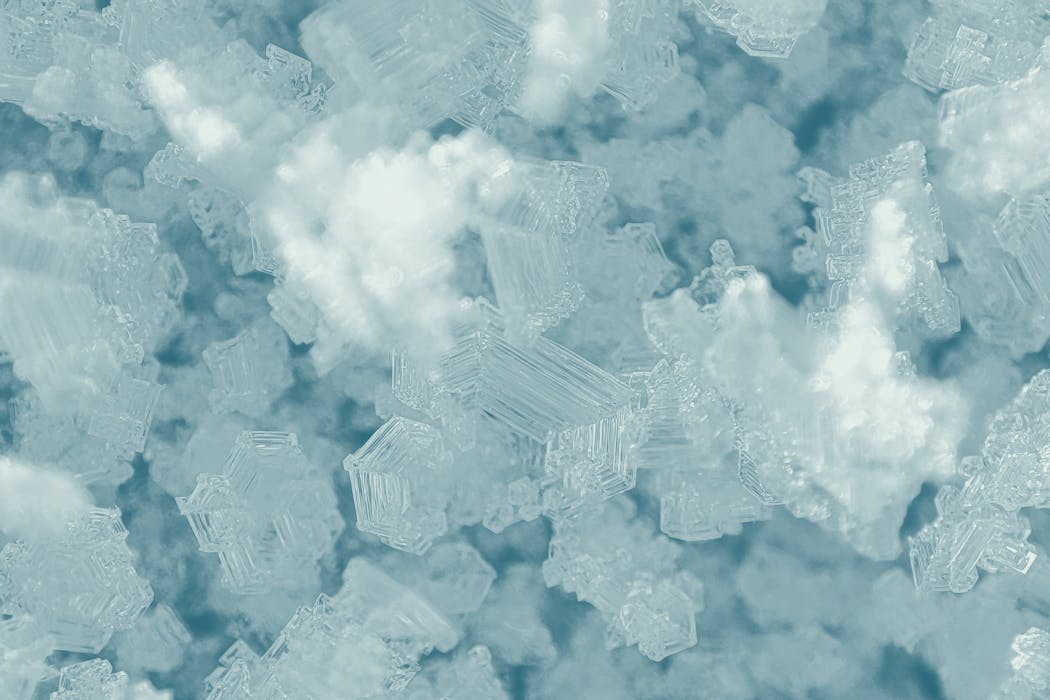

Astrid Gast/Shutterstock

HCFCs and HFCs have now been phased down under various amendments to the 1987 Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer, because they are potent greenhouse gases. Despite this, TFA production increased over the period with the peak production projected to be anywhere between 2025 and 2100.

By comparing the amounts of TFA in our model to Arctic ice core records, we found that these sources can explain virtually all of the TFA deposited in the Arctic. This is particularly concerning because it highlights the ability of TFA pollution to spread around the globe. Emissions from highly populated regions in the northern hemisphere can have a big effect on far-flung regions once considered to be pristine, such as the Arctic.

Read more:

What’s the forever chemical TFA doing in the UK’s rivers?

Peak TFA

However, when we compared our model results to rainwater concentrations closer to emissions regions in developed countries with extensive infrastructure or manufacturing, we found that the sources in our model could not explain all the observed TFA. We questioned whether this missing TFA could be explained by a refrigerant known as HFO-1234yf. This chemical is increasingly used in vehicle air-conditioning because of its low impact on global warming.

While often promoted as a sustainable climate-friendly alternative to HFCs, hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) can produce TFA much more quickly than HFCs (this process takes days for HFOs and years for HFCs). This may mean that the HFOs don’t travel as far in the atmosphere before breaking down, so more TFA gets deposited back on land closer to the regions they are emitted from.

By adding estimated emissions of HFO-1234yf to the model, we were able to considerably explain the gap between the predicted and actual measurements of TFA.

Emissions of HFOs are highly uncertain, so there may be other unknown sources contributing to the TFA observed in rainwater. But with the increasing use of HFOs, TFA will certainly continue to accumulate in the environment. The peak of TFA emissions from these sources will be well into the future if left unregulated now.

Given the risk of its irreversible accumulation in the environment, animals and people, plus a growing understanding of its effects on human health and nature, preventing pollution at source is the safest and healthiest option.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Lucy Hart receives funding from Natural Environment Research Council ECORISC CDT.

Ryan Hossaini receives funding from the Natural Environment Research Council

– ref. CFC replacements cause vast ‘forever chemical’ pollution – new research – https://theconversation.com/cfc-replacements-cause-vast-forever-chemical-pollution-new-research-274776