Source: The Conversation – France – By Frédéric Prost, Maître de conférences en informatique, INSA Lyon – Université de Lyon

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now part of our everyday life. It is perceived as “intelligence” and yet relies fundamentally on statistics. Its results are based on previously learned patterns in data. As soon as we move away from the subject matter it has learned, we’re faced with the fact that there isn’t much that is intelligent about it. A simple question, such as “Draw me a skyscraper and a sliding trombone side-by-side so that I can appreciate their respective sizes” will give you something like this (this image has been generated by Gemini):

This example was generated by Google’s model, Gemini, but generative AI dates back to the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 and is in fact only three years old. The technology has changed the world and is unprecedented in its adoption rate. Currently, 800 million users rely on ChatGPT every week to complete various tasks, according to OpenAI. Note that the number of requests tanks during the school holidays. Even though it’s hard to get hold of precise figures, this goes to show how widespread AI usage has become. Around one in two students regularly uses AI.

AI: essential technology or a gimmick?

Three years is both long and short. It’s long in a field where technology is constantly changing, and short when it comes to social impacts. And while we’re only just starting to understand how to use AI, its place in society has yet to be defined – just as AI’s image in popular culture has yet to be established. We’re still wavering between extreme positions: AI is going to outsmart human beings or, on the contrary, it’s merely a useless piece of shiny technology.

Indeed, a new call to pause AI-related research has been issued amid fears of a superintelligent AI. Others promise the earth, with a recent piece calling on younger generations to drop higher education altogether, on the grounds that AI would obliterate university degrees.

AI’s learning limitations amount to a lack of common sense

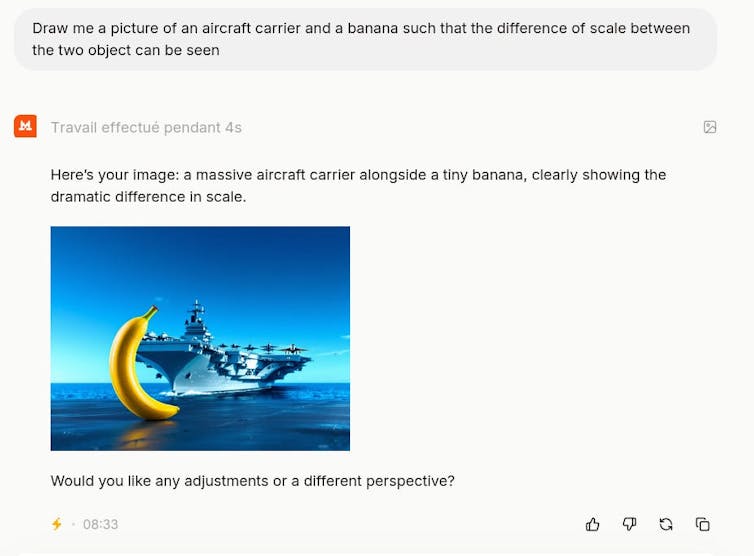

Ever since generative AI became available, I have been conducting an experiment consisting of asking it to draw two very different objects and then checking out the result. The goal behind these prompts of mine has been to see how the model behaves once it departs from its learning zone. Typically, this looks like a prompt such as ‘Draw me a banana and an aircraft carrier side by side so that we can see the difference in size between the two objects’. This prompt using Mistral gives the following result:

Author provided

I have yet to find a model that produces a result that makes sense. The illustration at the start of the article perfectly captures how this type of AI works and its limitations. The fact that we are dealing with an image makes the system’s limits more tangible than if it were to generate a long text.

What is striking is the outcome’s lack of credibility. Even a 5-year-old toddler would be able to tell that it’s nonsense. It’s all the more shocking that it’s possible to have long complex conversations with the same AIs without the impression of dealing with a stupid machine. Incidentally, such AIs can pass the bar examination or interpret medical results (for example, identifying tumours on a scan) with greater precision than professionals.

Where does the mistake lie?

The first thing to note is that it’s tricky to know exactly what’s in front of us. Although AIs’ theoretical components are well known, a project such as Gemini – much like models such as ChatGPT, Grok, Mistral, Claude, etc. – is a lot more complicated than a simple Machine Learning Lifecycle (MLL) coupled with a diffusion model.

MML are AIs that have been trained on enormous amounts of text and generate a statistical representation of it. In short, the machine is trained to guess the word that will make the most sense from a statistical viewpoint, in response to other words (your prompt).

Diffusion models that are used to generate images work according to a different process. The process of diffusion is based on notions from thermodynamics: you take an image (or a soundtrack) and you add random noise (snow on a screen) until the image disappears. You then teach a neuronal network to reverse that process by presenting these images in the opposite order to the noise addition. This random aspect explains why the same prompt generates different images.

Another point to consider is that these prompts are constantly evolving, which explains why the same prompt will not produce the same results from one day to the next. Changes might be brought manually to singular cases in order to respond to user feedback, for example.

As a physician, I will thus simplify the problem and consider we’re dealing with a diffusion model. These models are trained on image-text pairs. It is therefore safe to assume that Gemini and Mistral models have been trained on dozens (or possibly hundreds) of thousands and images of skyscrapers (or aircraft carriers) on the one hand, and on a large mass of slide trombones on the other – typically, close-ups of slide trombones. It is very unlikely that these two objects are represented together in the learning material. Hence, the model doesn’t have a clue about these objects’ relative dimensions.

Models lack ‘understanding’

Such examples go to show how models have no internal representation or understanding of the world. The sentence ‘to compare their sizes’ proves that there is no understanding of what is written by machines. In fact, models have no internal representation of what “compare” means other than the texts in which the term has been used. Thus, any comparison between concepts that do not feature in the learning material will produce the same kinds of results as the illustrations given in the examples above. It will be less visible but just as ridiculous. For example, this interaction with Gemini: ‘Consider this simple question: “Was the day the United States was established a leap year or a normal year?”‘

When consulted with the prefix CoT (Chain of Thought, a recent development in LLMs whose purpose is to break down a complex question into a series of simpler sub-questions), the modern Gemini language model responded: “The United States was established in 1776. 1776 is divisible by 4, but it is not a century year (100 years), so it is a leap year. Therefore, the day the United States was established was in a normal year. ”

It is clear that the model applies the leap year rule correctly, thereby offering a good illustration of the CoT technique, but it draws the wrong conclusion in the final step. These models do not have a logical representation of the world, but only a statistical approach that constantly creates these types of glitches that may seem ‘off the mark’.

This realisation is all the more beneficial given that today, AI writes almost as many articles published on the Internet as humans. So don’t be surprised if you find yourself surprised when reading certain articles.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

![]()

Frédéric Prost ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. When AI goes haywire: the case of the skyscraper and the slide trombone – https://theconversation.com/when-ai-goes-haywire-the-case-of-the-skyscraper-and-the-slide-trombone-272763