Source: The Conversation – USA – By Michele Heisler, Professor of Internal Medicine and Health Behavior and Health Equity, University of Michigan

Images and videos from Minneapolis, Chicago and other U.S. cities show masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol agents in military-style gear pointing weapons at people protesting or observing immigration enforcement actions. These are not typical firearms; they are riot control agents, and they emit cascades of projectiles or plumes of smoke.

In other scenes unfolding in cities across the country, officers launch metal canisters that explode loudly and scatter blinding flashes of light. The people targeted are shown screaming, disoriented and in some cases bleeding after being struck at close range. Those enveloped by smoke frequently cough and gasp for air.

What exactly are these weapons? What do they do to the human body? Are there rules governing their use? And what are their short- and long-term health effects?

As physician-researchers who have investigated the health consequences of human rights violations for decades, including misuse of so-called less lethal weapons in multiple countries, including the United States, we have studied how these tools are deployed and the harms that can result.

What are less lethal weapons?

U.S. law enforcement and federal agents deploy four main categories of crowd-control weapons: chemical irritants, kinetic impact projectiles known as KIPs, disorientation devices and electronic control weapons.

These weapons have been dubbed “less lethal” compared with live ammunition. But “less lethal” does not mean harmless. They can cause pain, fear and physiological stress and can result in serious injury or death.

AP Photo/Adam Gray

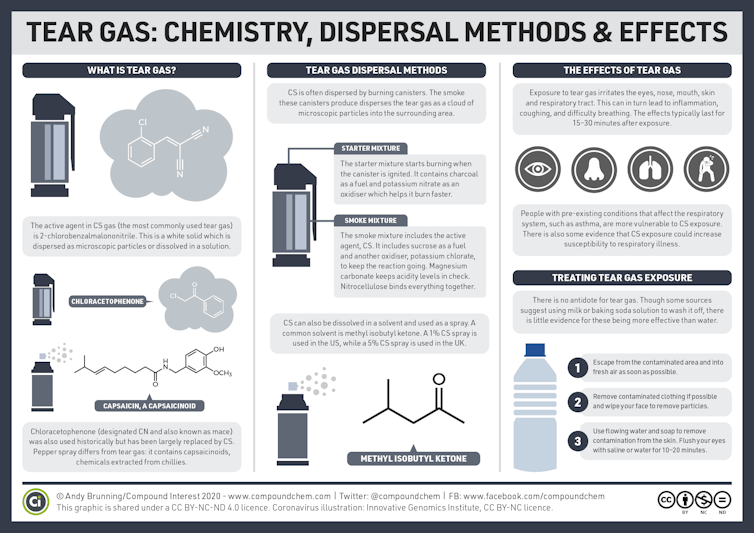

Chemical irritants, commonly called tear gas, cause intense pain and irritation of the eyes, skin and upper respiratory tract. They trigger coughing, breathing difficulty, disorientation, vomiting and panic. Delivered through sprays, pellets or canisters, they are inherently indiscriminate, affecting anyone in the area.

The most widely used agents in tear gas include chlorobenzylidene malononitrile, CS for short, and oleoresin capsicum, or OC, also called pepper spray. OC contains capsaicin, which is the compound that gives chiles their burning heat, at concentrations thousands of times stronger than those found in natural peppers. A synthetic version known as PAVA is also sometimes used. The amount, composition and concentration released can vary widely by manufacturer and country and remain largely unregulated. The spray can eject forcefully, reaching up to 20 feet depending on the canister design.

Andy Brunning/Compound Interest 2020, CC BY-NC-ND

Kinetic impact projectiles transfer energy from a moving object into the body. Often called rubber bullets, they may be made of rubber, plastic, metal, foam, wood or composite materials. Some are fired as single projectiles, while others are dispersed in multiple pellets. Injury risk depends on the projectile’s size, speed, material, direction and firing distance.

Flash-bang grenades, or stun grenades, are designed to disorient through a combination of deafening noise, blinding light, heat, fragmentation and pressure. Some devices produce sound levels above 170 decibels – far louder than most gunshots.

Electronic conduction devices, such as Tasers, have historically been used in individual arrests, but they are increasingly used in protest policing. Metal barbs from the device lodge in the skin and deliver high-voltage electrical current, causing intense pain and temporary loss of muscle control.

More recently, electrified shields and devices attached to an officer’s body or equipment – previously used inside prisons – have appeared at protests in some countries.

How are less lethal weapons supposed to be used?

In 2020 the United Nations issued detailed guidance on the use of less lethal weapons in law enforcement. In 2023 we worked with Physicians for Human Rights and the International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations to conduct updated analyses of these weapons.

The U.N. basic principles on the use of force and firearms specify that force should be used only as a last resort, and it should be proportionate to the threat. Officers using force should protect bystanders and vulnerable populations, such as children and older adults, and stop once the threat has ended.

Similar principles appear in use-of-force policies adopted by most U.S. police departments, though adherence is uneven. The Department of Homeland Security and specifically ICE have older published guidance. Recent ICE actions appear to breach that already vague language.

A 2021 Government Accountability Office report found that most ICE agents do not receive specialized training in the safe and appropriate use of crowd-control weapons, and training appears to be more limited now.

According to the U.N. guidelines, before deploying such weapons, well-trained officers are expected to assess whether a genuine threat exists, communicate with demonstration leadership when possible, consider alternative options and provide clear warnings. If officers use crowd-control weapons, they should be deployed to minimize injury and avoid indiscriminate harm.

Allison Dinner/AFP via Getty Images

For proper deployment, the U.N. use of force guidelines stipulate that officers should not fire weapons directly at individuals, and they should avoid the head and face. They should communicate prior to deploying, use only the minimum amount necessary and maintain safe exit routes.

In practice, these safeguards can be difficult to implement in fast-moving, crowded environments

Potential health harms

Crowd-control weapons can cause severe and sometimes permanent injuries. Chemical irritants affect the eyes, skin and lungs first, causing scratches to the surface of the eye, painful skin reactions, breathing difficulties and acute psychological distress. Some people develop longer-term post-traumatic stress disorder.

Our global review of the medical literature documented more than 100,000 injuries from chemical irritants between 2016 and 2021, along with at least 14 deaths, all due to blunt trauma from canisters. Higher concentrations or prolonged exposure increase the risk of serious and permanent injuries, including open sores on the surface of the eye, chemical burns and chronic respiratory disease.

Kinetic impact projectiles can cause both blunt and penetrating injuries, with eye injuries among the most severe. Direct impact often results in permanent blindness and, in rare cases, penetration of the brain through the eye socket.

Blunt head trauma from these projectiles can cause concussions, internal bleeding, skull fractures and lasting neurological damage. Projectiles striking the chest, abdomen or genitalia can injure vital organs. Risk is highest when KIPs contain metal components, are fired at close range or disperse multiple projectiles.

Our global 2017 systematic review identified nearly 2,000 people injured by KIPs over 25 years, including 53 deaths and hundreds of permanent disabilities. Subsequent reviews documented thousands more injuries worldwide, many resulting in permanent disability or death.

Flash-bang grenades also pose significant risks. Investigative reporting and medical analyses have documented dozens of severe injuries and deaths linked to their use in the United States. These devices have caused deep burns, hearing loss and blast-related trauma, particularly when deployed in enclosed spaces or thrown directly at individuals. When fired toward a person, these devices can also act as kinetic projectiles, compounding the risk of serious injury.

Electronic conduction devices can cause dangerous heart rhythm problems and electrocution injuries. They also can rip the skin when barbs strike sensitive areas, such as the eyes or genitalia.

In practice, the harm these “less lethal” weapons can cause depends less on what they’re called than on how, where and against whom they’re used. In the absence of clearer limits and oversight, people exercising their right to protest face real risks of injury.

From a medical perspective, people exposed to crowd-control weapons should move to fresh air, rinse exposed skin and eyes with clean water, and remove contaminated clothing as soon as possible.

Anyone struck by a projectile or exposed to a flash-bang should seek medical evaluation, even if they don’t have immediately obvious injuries. Internal injuries, eye damage, hearing loss or brain injury may not be apparent at first. Persistent eye pain, vision changes, breathing difficulty, chest symptoms, severe pain, or confusion warrant prompt medical care, particularly for children, older adults and people with underlying health conditions.

![]()

Michele Heisler is affiliated with Physicians for Human Rights, a non-partisan nongovernmental health and human rights organization that leverages medical, scientific, and public health evidence/research to document the health effects of human rights violations.

She currently has research funding from the NIDDK, NHLBI, American Diabetes Association and the Wellcome Trust but not for any research related to the topic of less-lethal weapons.

Rohini J Haar serves as a medical expert and consultant at Physicians for Human Rights, a non-partisan nongovernmental health and human rights organization that leverages medical, scientific, and public health evidence/research to document the health effects of human rights violations. She is not engaged in any partisan political activities as a volunteer or member.

– ref. ‘Less lethal’ crowd-control weapons still cause harm – 2 physicians explain what they are and their health effects – https://theconversation.com/less-lethal-crowd-control-weapons-still-cause-harm-2-physicians-explain-what-they-are-and-their-health-effects-274809