Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Meaghan O’Donnell, Professor and Head, Research, Phoenix Australia, Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, The University of Melbourne

In their day-to-day work, first responders – including police, firefighters, paramedics and lifesavers – often witness terrible things happening to other people, and may be in danger themselves.

For some people, this can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which usually involves intrusive memories and flashbacks, negative thoughts and emotions, feeling constantly on guard, and avoiding things that remind them of the trauma.

But our research – which tested a mobile app focused on building resilience with firefighters – shows PTSD isn’t inevitable. We found depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms were less likely when firefighters used a mental health program that was self-led, specifically addressed trauma and focused on teaching practical skills.

First responders’ mental health

First responders report high rates of psychiatric disorders and often have symptoms of depression (such as persistent feelings of sadness), anxiety (such as nervousness or restlessness) and post-traumatic stress (including distressing flashbacks).

Sometimes symptoms aren’t severe enough for a diagnosis.

But left untreated,these “sub-clinical” symptoms can escalate into PTSD, which can severely impact day-to-day life. So targeting symptoms early is important.

However, stigma – as well as concerns about confidentiality and career implications – can prevent first responders from seeking help.

What we already knew about building resilience

For the past decade, we have been testing a program designed to give people exposed to traumatic events the skills to manage their distress and foster their own recovery.

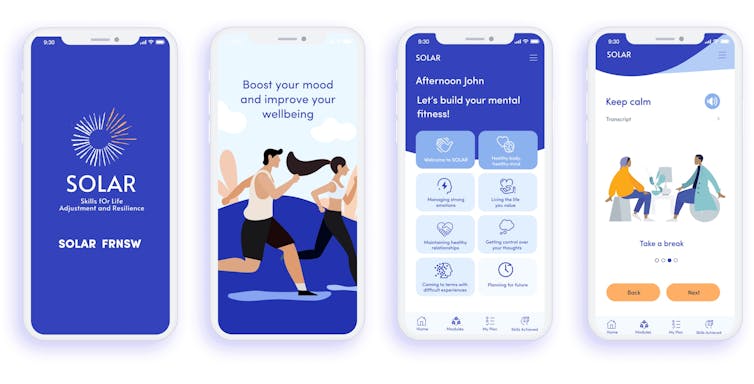

The “Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience” (SOLAR) program is:

- skills-based – it teaches people specific strategies and tools to improve their mental health

- trauma-informed, meaning it has been designed for people who have been exposed to trauma, and avoids re-traumatisation

- and has a psychosocial focus, focusing on what people can do in their relationships, behaviour and thinking to improve their mental health.

Participants complete modules focused on:

- the connection between physical health and mental health

- staying socially connected

- managing strong emotions

- engaging and re-engaging in meaningful activities

- coming to terms with traumatic events

- managing worry and rumination.

The SOLAR program trains coaches to deliver these modules in their communities. Importantly, these coaches don’t necessarily have specific mental health training, such as Australian Red Cross volunteers, community nurses and case workers.

What our new research did

The evidence shows the SOLAR program is effective at improving wellbeing and reducing depression, post-traumatic stress and anxiety symptoms.

But working with firefighters in New South Wales, they told us they wanted a self-led program they could complete confidentially, independently of their employer, and in their own time – a mobile app. So we wanted to test if the program would still be effective delivered this way.

A total of 163 firefighters took part in our recent randomised control trial, either using the app we co-designed with them, or a mood monitoring app.

A mood monitoring app tracks daily emotions to help understand patterns in how someone is feeling. There is evidence to show it can be useful for some people in reducing symptoms.

But this kind of app doesn’t teach a person practical skills that can be applied to different situations. And it does not specifically address stressful or traumatic experiences. So we wanted to test if taking a skills approach made a significant difference.

Spark Digital

What we found

Eight weeks after they started using one of the two apps, we followed up with the firefighters.

The study found those who used the SOLAR app had significantly lower symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress, compared to those in the mood monitoring group.

We followed up with participants again three months after their post-treatment assessment.

We found:

- depression was much lower in the group who learned practical skills about trauma, compared to those who used the mood monitoring app, and

- anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms had reduced significantly for both groups since starting their program (but there was no real difference between them).

What does this mean?

Both apps improved mental health.

But the results show using the SOLAR app, which focused on building skills and specifically addressing trauma, reduced mental symptoms more quickly. It was especially useful for tackling depression longer term.

Firefighters also told us they liked the app. This is important – an app is only effective when people use it.

Around half of the firefighters started using it completed all the modules. This is much higher than usual for mental health apps. Typically, only around 3% of those who start using a mental health app complete them.

The more modules a firefighter completed, the more their mental health improved.

The takeaway

It’s common for firefighters and other first responders to struggle with mental health symptoms. Our study demonstrates the importance of intervening early and teaching practical skills for resilience, so that those symptoms don’t develop into a disorder such as PTSD.

A program that is self-led, confidential and evidence-based can help protect the mental health of first responders while they do the work they love, protecting us.

![]()

Meaghan O’Donnell (Phoenix Australia) receives funding from government funding bodies such as National Health and Medical Research Council, and Department of Veterans’ Affairs, and philanthropic bodies such as Wellcome Trust Fund (UK), Latrobe Health Foundation, and Ramsay Health Foundation. Funding for this study in this Conversation article was from icare, NSW.

Tracey Varker (Phoenix Australia) receives funding from government funding bodies such as Department of Veterans’ Affairs, and philanthropic foundations such as Latrobe Health Services Foundation. Funding for the study described in this Conversation article was from icare NSW.

– ref. Firefighters face repeat trauma. We learned how to reduce their risk of PTSD – https://theconversation.com/firefighters-face-repeat-trauma-we-learned-how-to-reduce-their-risk-of-ptsd-269283