Source: The Conversation – in French – By Marion Di Ciaccio, Chair de Professeur Junior IRD, Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD)

L’éducation par les pairs – délivrée par des personnes issues d’une même communauté – est un pilier de la lutte contre le VIH, en particulier dans les pays à ressources limitées. Les réductions drastiques de l’aide publique au développement menées par l’administration Trump, comme par les principaux pays européens donateurs, mettent à mal cette stratégie de santé communautaire qui a pourtant fait ses preuves.

S’appuyer sur des individus au sein d’une communauté donnée pour informer et sensibiliser leurs pairs, afin de promouvoir des comportements de prévention, leur accès à une prise en charge et/ou leur maintien dans les soins, c’est le principe d’une stratégie de santé communautaire baptisée pair éducation ou éducation par les pairs.

L’éducation par les pairs est apparue dans les années 1970 dans les pays anglo-saxons, notamment dans le champ de la santé mentale et de la lutte contre les inégalités sociales de santé des minorités ethniques et raciales. Dans la lutte contre le VIH, la pair éducation est devenue une stratégie incontournable, notamment dans les pays à ressources limitées.

Volontariat, motivation, partage des vécus

La spécificité de la pair éducation est de s’appuyer sur une dynamique de relation d’égal à égal. Les pairs éducatrices ou éducateurs (PE) partagent des pratiques, des vécus, des identités et des réalités communes avec une population donnée et sont recruté·e·s sur la base du volontariat et de leur motivation pour travailler auprès d’elle.

Les PE sont formé·e·s afin de leur permettre d’acquérir de nouvelles compétences sur la gestion du VIH et sur la connaissance des systèmes de santé afin de renforcer leurs savoirs et leurs expertises.

Les PE peuvent ainsi promouvoir des pratiques et des comportements favorables à la santé physique et mentale auprès de leurs pairs, en tenant compte des réalités dans lesquelles ils et elles vivent.

Qui sont les pairs éducatrices et éducateurs dans le VIH ?

Les pairs éducatrices ou éducateurs (PE) sont le plus souvent issu·e·s des organisations communautaires de lutte contre le VIH et/ou contre les discriminations. Leur mobilisation répond au besoin de sensibiliser et d’accompagner des catégories spécifiquement vulnérabilisées de la population qui supportent le double fardeau de la stigmatisation liée au VIH et de la discrimination sociale.

Les vulnérabilités psychologiques, sociales, économiques, cliniques et de genre chez les adolescentes et adolescents infecté·e·s par le VIH ont été largement démontrées et sont souvent similaires quelle que soit l’histoire de la contamination par le VIH, périnatale ou plus récente. Les PE qui les accompagnent sont donc des jeunes (15-24 ans) vivant avec le VIH qui contribuent à la continuité d’une offre de soins et de support adaptée aux besoins spécifiques des filles et des garçons, entre les services de pédiatrie et de médecine adulte.

Les PE proviennent également de groupes considérés par l’Onusida comme les « populations clés du VIH » : les hommes ayant des rapports sexuels avec des hommes, les travailleuses et travailleurs du sexe ou encore les consommateurs de drogues injectables. En effet, ces groupes ont des besoins psychosociaux spécifiques (liés à leurs conditions de vie et aux discriminations subies) que les structures publiques de santé ne sont généralement pas en mesure de prendre en charge.

Ainsi, les PE sont principalement des personnes (à partir de 15 ans) vivant avec le VIH ou fortement exposées au risque d’infection. Parce qu’elles ou ils ont une histoire ou des pratiques communes, les PE sont les mieux placés pour accompagner ces groupes vulnérabilisés dans un parcours de prévention ou de soins.

Pourquoi la pair éducation est cruciale dans la lutte contre le VIH

La lutte contre le VIH est jalonnée depuis ses débuts par la participation inédite de mouvements communautaires pour l’accès aux traitements et à la prévention. Les personnes concernées (vivant avec) et affectées (groupes principalement concernés par le VIH) ont rapidement su imposer le concept du « Rien pour nous sans nous » dans la recherche et la lutte contre le VIH, imposant une nouvelle façon de faire de la recherche et de proposer des services de santé.

Dans ce contexte, les PE effectuent un travail de proximité qui permet :

-

i) d’améliorer le bien-être physique et mental des personnes,

-

ii) de connecter les populations vulnérabilisées/clés et les services de prise en charge du VIH et

Depuis plus de deux décennies, l’engagement de jeunes PE auprès des adolescentes et adolescents est déterminant dans la prise en charge du VIH. Ils interviennent, par exemple, pour soutenir leur observance aux traitements, pour favoriser leur rétention dans les soins et leur bien-être psychosocial, pour les accompagner après l’annonce de leur sérologie VIH, pour les soutenir dans le partage de leur sérologie avec leur entourage et lutter contre l’autostigmatisation ainsi que l’isolement, ou encore pour renforcer leurs connaissances en santé et concernant le VIH en particulier.

Une revue systématique de la littérature scientifique publiée, ainsi qu’une méta-analyse de toutes les études identifiées dans cette revue, montre que la pair éducation a également des bénéfices directs sur la prévention du VIH auprès des populations clés, et notamment sur le recours au dépistage du VIH, l’utilisation du préservatif, la diminution du partage du matériel de consommation de drogues et la diminution des rapports sexuels non protégés.

Les PE apportent aussi une plus-value importante aux programmes de PrEP (prophylaxie préexposition de l’infection VIH, un traitement préventif oral contre l’infection au VIH). En effet, il a été démontré au sein d’une cohorte en Afrique de l’Ouest que les hommes ayant des relations sexuelles avec des hommes qui étaient en contact avec des PE prenaient mieux la PrEP que les autres.

À lire aussi :

Médicaments antirétroviraux injectables contre le VIH : une évaluation impossible en Afrique de l’Ouest ?

Une étude qualitative menée au Mali montre également que les PE jouent un rôle crucial pour le maintien dans les soins des personnes vivant avec le VIH grâce, à la fois, au soutien psychosocial qu’ils leur apportent mais également grâce à leur soutien dans l’accès aux traitements.

La pair éducation est donc cruciale non seulement au niveau individuel pour améliorer la santé et la qualité de vie des groupes clés et vulnérabilisés, mais également au niveau global pour contrôler l’épidémie de VIH.

Dans le cadre de projets de recherche, les PE sont également des acteurs clés qui, en collaborant avec les équipes de recherche, permettent d’identifier des problématiques émergentes dans leurs communautés, de faciliter le contact avec des populations plus difficiles d’accès, d’adapter les méthodologies et les pratiques de recherches à leurs réalités, ainsi qu’à mieux interpréter les données issues des projets.

Quel impact de la réduction de l’aide publique au développement ?

L’expertise et la contribution précieuse à la lutte contre le VIH des PE n’est bien souvent reconnue et valorisée qu’à travers des financements issus de l’aide au développement, de programmes de mises en œuvre de prestations de santé communautaire innovantes, ou encore de projets de recherche communautaire et interventionnelle. Cette configuration précarise encore davantage leur position et la pérennité des services qu’ils apportent aux personnes qu’ils accompagnent, pourtant avec succès.

Depuis début 2025, le financement de l’aide publique au développement connaît de nombreux bouleversements. L’événement le plus notable est l’arrêt et/ou la réduction brutale des financements américains (par l’intermédiaire des programmes PEPFAR et USAID, notamment). L’aide publique au développement européen connaît également de fortes diminutions. En effet, les principaux pays donateurs (la France, l’Allemagne, le Royaume-Uni et les Pays-Bas) annoncent des baisses conséquentes des budgets alloués.

Ces diminutions drastiques des financements peuvent remettre en question les progrès de la lutte contre le VIH dans les pays des Suds avec un risque accru de recrudescence de l’épidémie et d’augmentation des inégalités sociales d’accès aux soins.

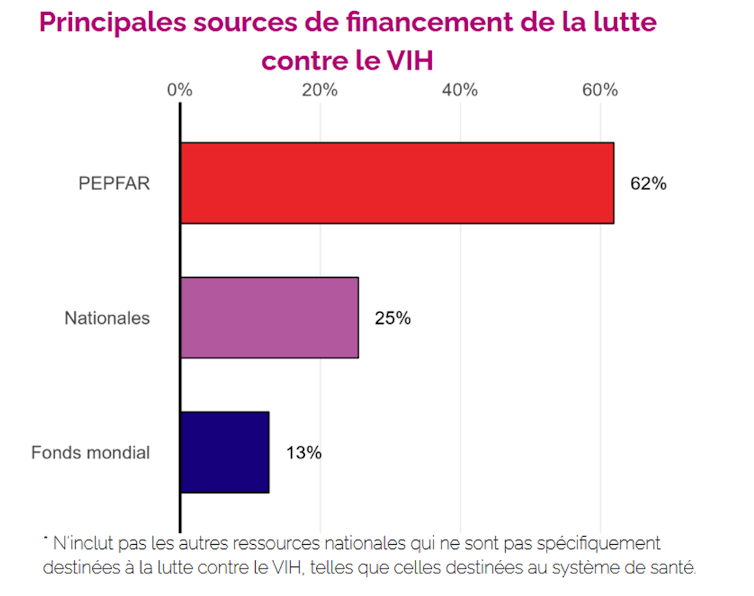

Les financements américains représentent une part considérable des ressources dédiées à la prévention, au dépistage, à l’accès aux traitements antirétroviraux et au renforcement des systèmes de santé locaux pouvant aller jusqu’à 60 % des financements de la lutte contre le VIH dans certains pays comme la Côte d’Ivoire (figure ci-dessous), le Cameroun ou encore le Burundi.

Exemple de la Côte d’Ivoire

PEPFAR pour « President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief » correspond au plan d’aide des États-Unis consacré à la lutte contre le VIH à l’international/Source des données présentées dans le graphique : Data Et cetera & Coalition PLUS, Fourni par l’auteur

Dans ces pays, les données collectées montrent que ce sont les programmes de prévention à destination des populations clés qui sont les plus touchés par les coupes budgétaires, incluant le financement des postes des PE (actuellement, uniquement dans le réseau d’organisations communautaires de Coalition PLUS – un réseau international d’associations engagées dans la lutte contre le VIH sida –, plus de 1 000 PE ne sont plus financés).

Le gel des financements a déjà eu des conséquences irréversibles sur la lutte contre le VIH. Les estimations montrent que la réduction de ces aides internationales pourrait entraîner de 4,43 millions à 10,75 millions de nouvelles infections par le VIH et de 0,77 millions à 2,93 millions de décès liés au VIH entre 2025 et 2030 dans les pays bénéficiaires de ces aides.

![]()

Marion Di Ciaccio est une ancienne salariée du pôle recherche communautaire de Coalition PLUS, une union internationale d’organisations communautaires de lutte contre le VIH.

Cécile Cames et Mathilde Perray ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur poste universitaire.

– ref. L’éducation par les pairs dans la lutte contre le VIH menacée par les réductions de l’aide publique au développement – https://theconversation.com/leducation-par-les-pairs-dans-la-lutte-contre-le-vih-menacee-par-les-reductions-de-laide-publique-au-developpement-264528