Source: The Conversation – UK – By Nic Sanders, Senior Lecturer in Management and Marketing, University of Westminster

Shopping for clothes online is a risky business. How do you know if that top will be a good fit, or those shoes will definitely be the right colour? One popular solution to this predicament is to order lots of tops and lots of shoes, try them on at home, and send back all the ones you don’t want – often at no cost.

But that tactic can be expensive for the fashion retailer, which needs to pay for all those deliveries and returns. And now Asos, which sends millions of shipments every month, has started banning some customers for over-returning items – prompting something of a backlash.

The response by the retail giant, which says it wants to maintain a “commitment to offering free returns to all customers across all core markets”, also raises questions about the sustainability of the online fashion business model which Asos helped to create.

Many online retailers rely on the emotional highs of shopping. The excitement of placing an order, the anticipation of delivery, and the dopamine hit of unpacking a purchase is central to its popular customer experience.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Online shopping generally has thrived on impulsive buying, with the option of returning items treated as a normal part of the process. Of course, even in the days before online shopping there would be customers who routinely returned items.

But by digitising and simplifying the process, the likes of Asos have helped this to happen on a massive scale. Shoppers have become completely used to ordering multiple sizes or styles with the express intention of returning most of the items they receive. Their homes effectively become fitting rooms.

And those customers could reasonably argue that online retailers often use digital strategies which encourage multi-item purchases.

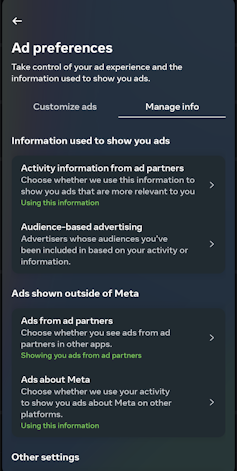

Some sites remind shoppers of recently viewed products and provide suggestions of similar items, for example. There may be are prompts and nudges towards clothes which are frequently bought together.

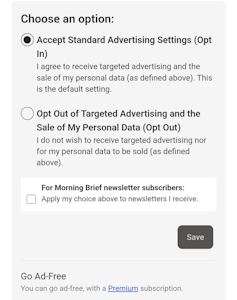

Items are then sometimes temporarily reserved in a shopper’s basket for 60 minutes, creating a sense of urgency. Targeted emails and limited time offers drive bulging shopping baskets, encouraging more risk purchases and returns.

Yet returned items carry a significant cost. They may be unfit for resale and ultimately disposed of, which beyond the financial burden, has an environmental price.

In addition to creating landfill, each delivery and return has a carbon footprint. And although many younger consumers express support for sustainable practices, their buying behaviour continues to prioritise price and convenience.

But free returns have become part of the online fashion industry landscape. Research suggests that customers are simply more likely to buy something if returns are free.

And today’s tricky financial climate, marked by inflation and rising living costs will surely have made consumers even more cautious. Many will be reluctant to buy items that incur delivery and return costs.

Shopping around

Frustrations can then arise from unclear return policies, often buried in lengthy terms and conditions documents. Some of those banned by Asos say they were confused about the rules.

Automated customer service systems offering generic responses may then leave shoppers with no clear way to challenge these decisions.

Perhaps the wider issue here is that online shopping cannot fully replicate the benefits of shopping in store. In physical shops, customers can try on items before deciding.

But online, this can’t happen, so returns become fundamental to the decision-making process. For cost-conscious shoppers, avoiding unnecessary spending is essential. But if returns policies become harder to access, they may turn to other retailers which offer more certainty.

A08/Shutterstock

For example, retailers such as Zara and H&M, with a business model which mixes online convenience with a high street (or shopping mall) presence, offer the option to order online and then return in person.

This hybrid (or “omni-channel”) model appears to be driving consumers to physical shops for a blended experience which provides convenience and helps reduce return costs.

For Asos, doing something similar would require major investment (in bricks and mortar) and increased operational costs – so is perhaps an unlikely solution for the company.

But to balance sustainability, cost and customer satisfaction, Asos could explore other options. These might include clearer, more visible communication regarding “fair use” policies and their consequences. It could aim for more human interactions and better dialogue with customers it plans to ban.

Offering physical retail locations or return collection points to simplify the process and reduce the environmental impact and costs will provide customer flexibility. Overall, these areas will help create a better customer service experience.

Ultimately, Asos and other similar online clothing retailers must evolve. With changing consumer expectations, a challenging economic climate and rising operational costs, the model that defined these retailers’ early success cannot remain unchanged.

If they make adjustments, they may emerge stronger. If they do not, they risk sparking a customer exodus that would be hard to reverse.

![]()

Nic Sanders does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why Asos should be wary of banning customers returning unwanted goods – https://theconversation.com/why-asos-should-be-wary-of-banning-customers-returning-unwanted-goods-259952