Source: The Conversation – UK – By Rebecca Wynne-Walsh, Lecturer in Film, English and Creative Arts, Edge Hill University

Sourcing family friendly frightening fiction can be a bit challenging. That said, while straightforward horror texts rarely serve family audiences, the gothic is a mode of storytelling that has a long history of delighting and disgusting parents and children alike.

Naturally, there is intellectual and stylistic value to both classic horror and the gothic. However, while horror interacts more directly with fear, the gothic favours observing the tension surrounding the source of fear.

Read more:

Scary stories for kids: these tales of terror made me a hit at sleepovers as a pre-teen

The stereotypical gothic heroine is not only trapped in the haunted house, she desires to understand it. Children’s books which use the gothic mode of storytelling encourage a similar investigative impulse in children. This is the modus operandi of the Scooby Doo gang, for example: research, exploration and answer-seeking rather than simply succumbing to fear.

Some iconic examples of children’s gothic literature include Neil Gaiman’s Coraline (2002), Roald Dahl’s The Witches (1983), The Spiderwick Chronicles (Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black, 2003 to 2009) and The Saga of Darren Shan (Darren Shan, 2000 to 2004).

This article is part of a series of expert recommendations of spooky stories – on screen and in print – for brave young souls. From the surprisingly dark depths of Watership Down to Tim Burton’s delightfully eerie kid-friendly films, there’s a whole haunted world out there just waiting for kids to explore. Dare to dive in here.

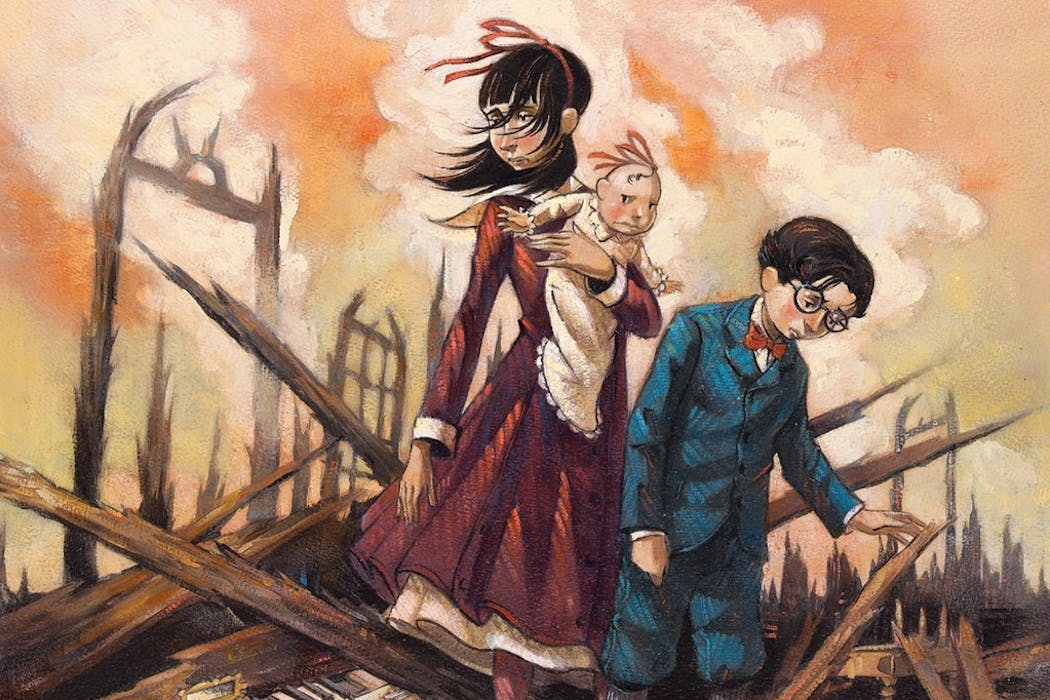

While these are all excellent tales, the spooky story which impacted me most as a child, and still does as an adult, is Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (1999 to 2006). This 13-book series follows three orphaned siblings, Violet, Klaus and Sunny Baudelaire as they are forced to navigate the homes of various (increasingly odd and occasionally villainous) guardians. All the while they try evade capture at the hand of evil Count Olaf who seeks their family fortune, and solve the mystery of what the VFD (Volunteer Fire Department) organisation is – the answer to which might hold the key their parents’ mysterious past.

I was five years old when I received a copy of the first book in the series, aptly titled, The Bad Beginning. That first foray into the dark world of the Baudelaires meant that for the next few years the days I got to go to the bookshop to get the next book were some of the most exciting I experienced.

Aside from being devilishly delightful tales full of mysteries, adventure, danger, songs and a surprising amount of food recipes, these books never shied away from the harsher elements of real life. Among many important lessons, Snicket also taught me that horseradish and wasabi are in the same family, that first impressions of new people aren’t always accurate and that grief may never be understood but can be managed.

As he writes in the second book, The Reptile Room:

[Grief] is like walking up the stairs to your bedroom in the dark, and thinking there is one more stair than there is. Your foot falls down, through the air, and there is a sickly moment of dark surprise as you try and readjust the way you thought of things.

During many of the most challenging parts of my childhood (and now my adulthood), these books offered me agency, riddles to solve, new words to learn, puzzles to put together and complex histories to understand. This is the core joy of these books – Snicket treats his intended readers (children) like people, instead of talking down to them.

The quirky and interactive elements of these books are a major factor in their enduring popularity. In an era of ever decreasing attention spans, Snicket offers an interactive reading experience in which no two chapters, and even no two pages are the same.

In one of the books, the Baudelaire children fall down a broken elevator shaft, a plot point illustrated literally by the three pitch black pages which “narrate” their descent. Another book sees the children receive a coded message, this chapter must be read in front of a mirror to decipher the backwards text. And most, if not all the books, incorporate poetry, songs, plays and paintings – which the Baudelaire orphans, and the readers, must use to decipher the mysteries surrounding the titular unfortunate events.

From the outset the reader is presented with total agency, invited to “shut the book” in a manner which directly encourages child autonomy. Nonetheless, children and adults alike have continued to engage with this franchise in all of its forms. Whether that be the original books, the 2004 feature film, the Netflix series released in 2017, the audiobooks narrated by Tim Curry, the concept album based on the books by The Gothic Archies or the ever updated Lemony Snicket website with multiple extra materials.

In short, the spooky gothic fun never has to end. As someone who has read these books annually since their original release, I can confidently attest to this as I continue to try and solve the eternal mystery of the VFD and the reason why Snicket’s villains are so damn villainous.

If you have not yet had the chance to enter the wild, woeful and wonderous world of the Baudelaire children and the mysteries surrounding their series of unfortunate events, I encourage readers of all ages to ignore Snicket’s suggestion to shut the books. Indeed, look to these tales, in the words of Snicket, to find a “small, safe place in a troubling world”.

The Series of Unfortunate Events is suitable for children aged 8 to 14.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Rebecca Wynne-Walsh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Scary stories for kids: A Series of Unfortunate Events taught me that grief can’t be understood but can be managed – https://theconversation.com/scary-stories-for-kids-a-series-of-unfortunate-events-taught-me-that-grief-cant-be-understood-but-can-be-managed-267786