Source: The Conversation – Africa – By Richard G. Cowden, Research Scientist, Harvard University

South Africa is often portrayed in the media as a country struggling with inequality, corruption, crime, infrastructure collapse and public health challenges. But this isn’t the whole story.

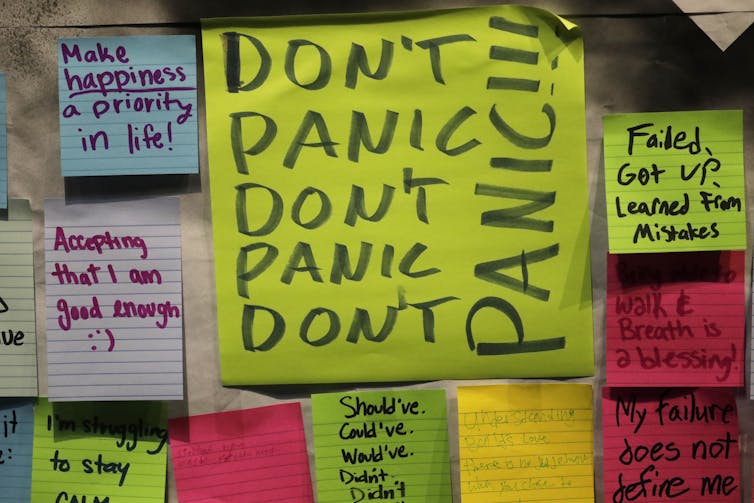

When South Africans are asked to describe their own lives, they often reveal signs that they are flourishing in vital ways. According to the Global Flourishing Study, many South Africans are in fact showing resolve by striving to move forward from the country’s difficult past and maintaining hope for a better future.

Human flourishing is sometimes used to describe an ideal state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good, including the environments and communities they’re part of. The global study was launched in 2021 to better understand human flourishing around the world.

Over 200,000 people in 22 countries from Argentina to Japan participated in the first wave of the Global Flourishing Study. They completed a survey about their background, upbringing, health, well-being, and other areas of life.

Recently, we analysed the data from 2,561 South Africans in the study to drill deeper. We explored how they are doing across nearly 70 health, well-being and related outcomes. The analysis offers the first comprehensive overview of flourishing in South Africa.

So, what does flourishing look like in South Africa right now?

Contrary to a gloomy view of the country, adult South Africans are flourishing in many ways that mirror the broader world. The country even has some notable strengths it could capitalise on. There are also lingering struggles that may be hindering flourishing in South Africa.

These findings show that some flourishing is still possible amid adversity. Insights from South Africa could offer clues about how to support the well-being of people living in places that are going through significant social and structural challenges.

What South Africa has in common with others

Part of our analysis compared South Africa’s average for each indicator of flourishing to the average across all other countries in the study.

For example, consider the question, “In general, how happy or unhappy do you usually feel?” (rated on a scale from 0-10, with 0 being extremely unhappy and 10 being extremely happy). The average response was 6.95 in South Africa and 7.00 across the other countries. This suggests average happiness in South Africa is about the same as in the other countries, taken together.

The findings were similar for more than 30 of the main outcomes, including sense of purpose, social belonging, depression, gratitude, and general health.

Despite deep-seated societal problems, many South Africans report experiences of well-being that are not very different from the rest of the world. This doesn’t mean that the country’s social and structural challenges should be minimised or overlooked. However, it does show that many people can still experience high levels of well-being in circumstances of material fragility and deprivation.

It raises questions for South African leaders, policymakers and citizens to reflect on. For example, what might the flourishing of South Africans look like if these social-structural constraints were loosened or lifted?

South Africa’s strengths

The findings also suggest that South Africans have several strengths. Compared with the combined averages of the other countries, South Africans reported lower pain and suffering, greater inner peace, hope and forgiveness of others, and greater religious or spiritual engagement. On many of these, South Africa was ranked among the top five countries.

This shines a light on the enormous potential for flourishing in South Africa. For instance, many South Africans say they have the capacity to reckon with wounds from the oppressive system of racial segregation that shaped society for decades (through forgiveness).

South Africans tend to stay grounded amid the challenges of daily life (through inner peace), which puts them in a position to transcend adversities. And they generally hold onto the possibility of a brighter future despite enduring social-structural vulnerabilities (through hope).

Perhaps the most inspiring of these findings is forgiveness. This is a strength that appears to have been cultivated through South Africa’s protracted reckoning with the legacy of apartheid. It may reflect a general societal commitment to pursuing peace and healing over discord and bitterness.

Faith may be a foundational source for the strengths seen in South Africa. For many South Africans, religion or spirituality is something they lean on to navigate the struggles they face in one of the most unequal societies in the world.

The challenges

Like many countries in the Global Flourishing Study, South Africa has clear opportunities to strengthen and expand the conditions that support human flourishing.

South Africans also tended to report lower well-being on several outcomes. These included satisfaction with life, meaning in life, place satisfaction, social trust, experiences of discrimination, charitable giving, and several socioeconomic factors such as employment and financial well-being.

Read more:

Which African countries are flourishing? Scientists have a new way of measuring well-being

These point to actionable areas that government, civil society, and private sector leaders can prioritise to improve flourishing in the country. Special attention should be directed toward supporting vulnerable groups that the analysis showed are struggling in many aspects of flourishing, including women, divorced people, and those with lower levels of education.

What this all means

The concept of flourishing invites South Africa to envision the highest ideals for its people and the kind of society those ideals might sustain. This does not mean that everyone will agree on what those ideals are, or how best to achieve them.

But the language of flourishing offers a way to unite different sectors and stakeholders around a shared goal: harnessing South Africa’s strengths while addressing challenges that hold back deeper forms of human flourishing in the country.

![]()

Richard G. Cowden does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. South Africans are flourishing more than you might expect – here’s why – https://theconversation.com/south-africans-are-flourishing-more-than-you-might-expect-heres-why-268695