Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Elizabeth Kusi Appiah, PhD Candidate, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta

Racism has long disrupted relationships, deepened social divisions and hindered collective action on global challenges. While modern societies strive to be just and advocate against social injustices, many still turn away from engaging in conversations surrounding racism, health inequities and racial tensions.

Yet these issues significantly impact health — including the care Black people receive and their health outcomes. Research shows that racism has many long-term effects on health, and is linked to both poorer mental and physical health overall.

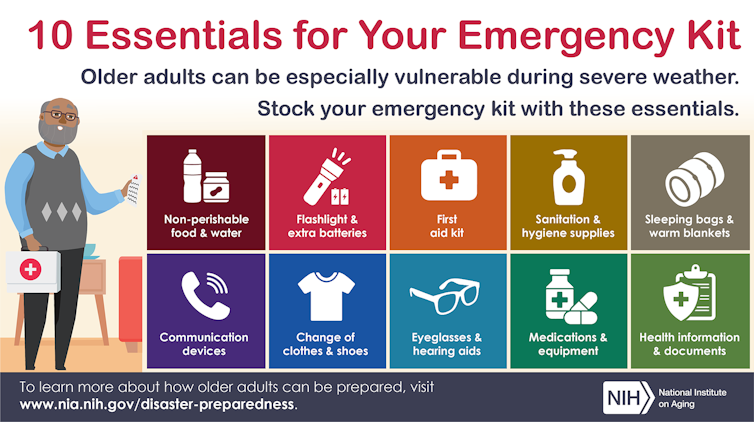

Black History Month is an opportunity to reflect critically on the impact of racism in health care and how to address it. As researchers focused on Black women’s acute and critical care experiences, our recent review draws lessons from studies on Black women’s health-care experiences in high-income countries to propose an approach for addressing racism.

The review included 10 studies conducted in the United States between 1987 and 2024. We found that Black women’s experiences in health care continue to be marked by reports of structural racism, microaggressions and persistent mistrust of the care system and care providers. Such experiences reduced the chances for shared decision-making, early detection of health issues, adherence to treatments, pain management and person-centred care.

We revealed that the enduring legacy of racism in medicine contributes to suboptimal communication and poor-quality care for Black women. Some of the women did not receive appropriate followup for diagnostic tests or see a specialist because their physician dismissed their concerns. Most of the women felt invisible because their providers disregarded their concerns. As a result, they felt discouraged from seeking care.

For instance, in one of the studies included in our review, a woman described her experiences of arriving at the emergency department for care. She said:

“As a Black woman I was told that it was a female problem, instead of my heart….The head doctor took a look at me and said, she doesn’t have a heart problem, this is absolutely no heart problem, it’s some kind of female problem. It was in my head.”

Another described feeling dismissed by doctors due to the way she described her pain, stating:

“I called it a wrecking ball pain. That’s what I was experiencing … Then my doctor, who likes to joke about everything, would say ‘Oh! Here’s the lady with the wrecking ball disease.’”

This left the patient feeling like a medical novelty — rather than being seen as a person worthy of respect and care.

Our discussions also identified how some Black adult patients responded to racial tensions and unjust conditions in their care.

When feeling disregarded by clinicians, some people purposefully limited what they shared. Others changed how they spoke to clinicians to fit white-dominated medical culture. Some even disengaged from the care decision-making process entirely — while others chose to advocate for themselves.

Further, if the physician appeared dismissive or disrespectful, some people ignored their medical advice as they felt the doctor didn’t have their best interests at heart. Others became hyper-vigilant against injustices and were likely to interpret subsequent care encounters based on past experiences.

Impact of racism on health care work

Health-care staff are compassionate people who want to provide the best care for patients. But they may not always be sure how to avoid getting it wrong.

Research indicates that nurses worry about getting it wrong and coming across as disrespectful when caring for people from different cultural backgrounds. Likewise, many nurses fear being labelled as racist, as they say it implies they’re a terrible person. Yet many are unwilling to accept personal responsibility for their actions — or inactions — if such a label is given to them.

There’s also a lack of clarity among nurses regarding what constitutes racist practices. This causes them anxiety. Some find it upsetting to think that their actions have been perceived as racist when that wasn’t their intention. Others are hesitant to express their genuine opinions on issues of this nature due to the fear of being called racist.

A separate study on nurse-patient relationships found that racism hinders nurses’ ability to meet a patient’s care needs and threatens patients’ and nurses’ dignity in the care system. Racism from patients also increases nurses’ stress and causes emotional trauma.

Racism in health-care settings continues to have a detrimental effect on the care patients are receiving. It’s clear institutions need to do more to ensure patients aren’t being harmed when receiving care.

Inclusive and nurturing communities

We believe that building inclusive and nurturing communities that counter racism and celebrate our interdependence is how we can move forward and address racism in health care.

Inclusive and nurturing communities equip people to have difficult conversations about race — whether that’s in health care, the classroom, universities, workplaces and neighbourhoods.

This type of community teaches people the importance of listening and engaging authentically and open-mindedly, and of learning about racism through the experiences of others. It doesn’t see people who engage in racist practices as inherently racist — but as people who need more support in recognizing and addressing racism.

In such spaces, every person bears a social responsibility to combat racism in their own ways — whether by fostering conversations about racism in their homes, workplaces or shared community spaces.

We’re hoping to conduct research investigating how such spaces can be built — and how this framework can be used in health-care settings to address the racism patients experience there.

We’re all part of the bigger picture. When we create safe and brave spaces for thinking, analyzing and talking about racial tensions, we’re inviting everyone to authentically participate in problem-solving.

Research shows trust is essential in building strong and productive human relations. So in order to build inclusive and nurturing communities, we need to invest time and effort into restoring the broken trust of racialized communities through accountability, transparency, consistency and genuine efforts to address systemic racism.

![]()

Elizabeth Kusi Appiah is affiliated with the GROWW national mentorship program.

Elisavet Papathanasoglou receives funding from Women & Children health Research Institute (WHCRI).

– ref. Black women’s health-care experiences remain marked by structural racism — here’s how institutions should move forward – https://theconversation.com/black-womens-health-care-experiences-remain-marked-by-structural-racism-heres-how-institutions-should-move-forward-250337