Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Jye Marshall, Lecturer, Fashion Design, School of Design and Architecture, Swinburne University of Technology

Valentino, who died on Monday at 93, leaves a lasting legacy full of celebrities, glamour and, in his words, knowing what women want: “to be beautiful”.

The Italian fashion powerhouse has secured his dream of making a lasting impact, outliving Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent.

Valentino was known for his unique blend between the bold and colourful Italian fashion and the elegant French haute couture – the highest level of craftsmanship in fashion, with exceptional detail and strict professional dressmaking standards.

The blending of these styles to create the signature Valentino silhouette made his style distinctive. Valentino’s style was reserved, and over his career he built upon the haute couture skills he had developed, maintaining his signature style while he led his fashion house for five decades.

But he was certainly not without his own controversial views on beauty for women.

Becoming the designer

Born in Voghera, Italy, in 1932, Valentino Clemente Ludovico began his career early, knowing from a young age he would pursue fashion.

He drew from a young age and studied fashion drawing at Santa Marta Institute of Fashion Drawing in Milan before honing his technical design skills at École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, the fashion trade association, in Paris.

He started his fashion career at two prominent Parisian haute couture houses, first at Jean Dessès before moving to Guy Laroche.

He opened his own fashion house in Italy in 1959.

His early work had a heavy French influence with simple, clean designs and complex silhouettes and construction. His early work had blocked colour and more of a minimalist approach, before his Italian culture really came through later in his collections.

He achieved early success through his connections to the Italian film industry, including dressing Elizabeth Taylor fresh off her appearance in Cleopatra (1963).

Keystone/Getty Images

Valentino joined the world stage on his first showing at the Pritti Palace in Florence in 1962.

His most notable collection during that era was in 1968 with The White Collection, a series of A-line dresses and classic suit jackets. The collection was striking: all in white, while Italy was all about colour.

He quickly grew in international popularity. He was beloved by European celebrities, and an elite group of women who were willing to spend the money – the dresses ran into the thousands of dollars.

In 1963, he travelled to the United States to attract Hollywood stars.

The Valentino woman

Valentino’s wish was to make women beautiful. He certainly attracted the A-list celebrities to do so. The Valentino woman was one who would hold themselves with confidence and a lady-like elegance.

Valentino wanted to see women attract attention with his classic silhouettes and balanced proportions. Valentino dressed women such as Jackie Kennedy, Audrey Hepburn, Julia Roberts, Gwyneth Paltrow and Anne Hathaway.

His aristocratic taste inherited ideas of beauty and old European style, rather than innovating with new trends. His signature style was formal designs that had the ability to quietly intimidate – including the insatiable Valentino red.

Red was a signature colour of his collections. The colour provided confidence and romance, while not distracting away from the beauty of the woman.

French influence

Being French-trained, Valentino was well acquainted with the rules of couture.

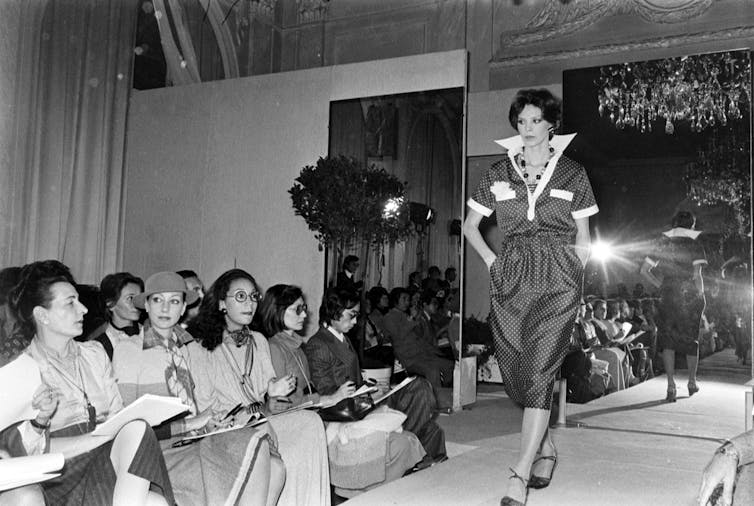

With this expertise, he was one of the first Italian designers to be successful in France as an outsider with the launch of his first Paris collection in 1975. This Paris collection showcased more relaxed silhouettes with many layers, playing towards the casual nature of fashion.

Guy Marineau/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

While his design base was in Rome, many of his collections were shown in Paris over the next four decades. His Italian culture mixed with the technicality of Parisian haute couture made Valentino the designer he was.

Throughout his career, his designs often maintained a classic silhouette bust, matched with a bold Italian colour or texture.

Unlike some designers today, Valentino’s collections didn’t change too dramatically each season. Instead, they continued to maintain the craftsmanship and high couture standards.

“Quintessentially beautiful” is often the description of Valentino’s work – however this devotion to high beauty standards has seen criticism of the industry. In 2007, Valentino defended the trend of very skinny women on runways, saying when “girls are skinny, the dresses are more attractive”.

Critics said his designs reinforce exclusion, gatekeeping fashion from those who don’t conform to traditional beauty standards.

The Valentino runways only recently have started to feature more average sized bodies and expand their definition of beauty.

The $300 million sale of Valentino

The Valentino fashion brand sold for US$300 million in 1998 to Holding di Partecipazioni Industriali, with Valentino still designing until his retirement in 2007.

Valentino sold to increase the size of his brand: he knew without the support of a larger corporation surviving alone would be impossible. Since Valentino’s retirement, the fashion house has continued under other creative directors.

Valentino will leave a lasting legacy as the Italian designer who managed to break through the noise of the French haute couture elite and make a name for himself.

The iconic Valentino red will forever be remembered for its glamour, and will live on with his legacy. A true Roman visionary with unmatched craftsmanship.

![]()

Jye Marshall does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Valentino shaped the runway – and the red carpet – for 60 years – https://theconversation.com/valentino-shaped-the-runway-and-the-red-carpet-for-60-years-273891