Source: – By Murugan Anandarajan, Professor of Decision Sciences and Management Information Systems, Drexel University

Every year, I tell my students in my business analytics class the same thing: “Don’t just apply for a job. Audition for it.”

This advice seems particularly relevant this year. In today’s turbulent economy, companies are still hiring, but they’re doing it a bit more carefully. More places are offering candidates short-term work experiences like internships and co-op programs in order to evaluate them before making them full-time offers.

This is just one of the findings of the 2025 College Hiring Outlook Report. This annual report tracks trends in the job market and offers valuable insights for both job seekers and employers. It is based on a national survey conducted in September 2024, with responses from 1,322 employers spanning all major industries and company sizes, from small firms to large enterprises. The survey looks at employer perspectives on entry-level hiring trends, skills demand and talent development strategies.

I am a professor of information systems at Drexel University’s LeBow College of Business in Philadelphia, and I co-authored this report along with a team of colleagues at the Center for Career Readiness.

Here’s what we found:

Employers are rethinking talent pipelines

Only 21% of the 1,322 employers we surveyed rated the current college hiring market as “excellent” or “very good,” which is a dramatic drop from 61% in 2023. This indicates that companies are becoming increasingly cautious about how they recruit and select new talent.

While confidence in full-time hiring has declined, employers are not stepping away from hiring altogether. Instead, they’re shifting to paid and unpaid internships, co-ops and contract-to-hire roles as a less risky route to identify talent and “de-risk” full-time hiring.

Employers we surveyed described internships as a cost-effective talent pipeline, and 70% told us they plan to maintain or increase their co-op and intern hiring in 2025. At a time when many companies are tightening their belts, hiring someone who’s already proved themselves saves on onboarding reduces turnover and minimizes potentially costly mishires.

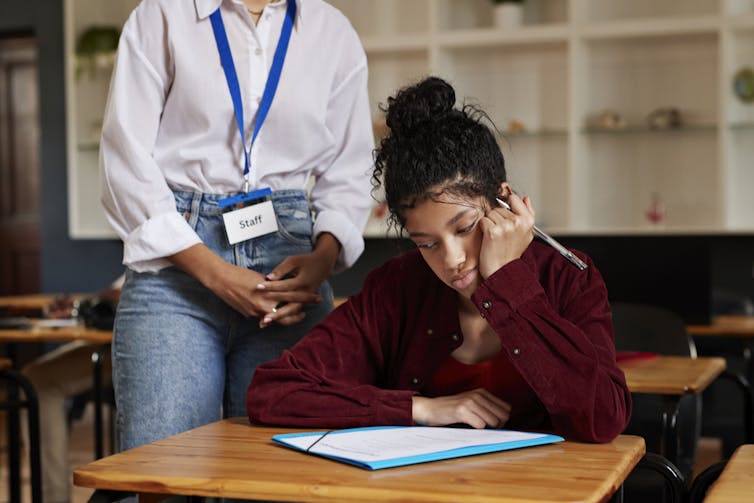

For job seekers, this makes every internship or short-term role more than a foot in the door. It’s an extended audition. Even with the general market looking unstable, interest in co-op and internship programs appears steady, especially among recent graduates facing fewer full-time opportunities.

These programs aren’t just about trying out a job. They let employers see if a candidate shows initiative, good judgment and the ability to work well on a team, which we found are traits employers value even more than technical skills.

What employers want

We found that employers increasingly prioritize self-management skills like adaptability, ethical reasoning and communication over technical skills such as digital literacy and cybersecurity. Employers are paying attention to how candidates behave during internships, how they take feedback, and whether they bring the mindset needed to grow with the company.

This reflects what I have observed in classrooms and in conversations with hiring managers: Credentials matter, but what truly sets candidates apart is how they present themselves and what they contribute to a company.

Based on co-op and internship data we’ve collected at Drexel, however, many students continue to believe that technical proficiency is the key to getting a job.

In my opinion, this disconnect reveals a critical gap in expectations: While students focus on hard skills to differentiate themselves, employers are looking for the human skills that indicate long-term potential, resilience and professionalism. This is especially true in the face of economic uncertainty and the ambiguous, fast-changing nature of today’s workplace.

Technology is changing how hiring happens

Employers also told us that artificial intelligence is now central to how both applicants and employers navigate the hiring process.

Some companies are increasingly using AI-powered platforms to transform their hiring processes. For example, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia uses platforms like HireVue to conduct asynchronous video interviews. HR-focused firms like Phenom and JJ Staffing Services also leverage technologies such as AI-based resume ranking, automated interview scheduling and one-way video assessments.

Not only do these tools speed up the hiring process, but they also reshape how employers and candidates interact. In our survey, large employers said they are increasingly relying on AI tools like resume screeners and one-way video interviews to manage large numbers of job applicants. As a result, the candidate’s presence, clarity in communication and authenticity are being evaluated even before a human recruiter becomes involved.

At the same time, job seekers are using generative AI tools to write cover letters, practice interviews or reformat resumes. These tools can help with preparation, but overreliance on them can backfire. Employers want authenticity, and many employers we surveyed mentioned they notice when applications seem overly robotic.

In my experience as a professor, the key is teaching students to use AI to enhance their effort and not replace it. I encourage them to leverage AI tools but always emphasize that the final output and the impression it makes should reflect their own thinking and professionalism. The bottom line is that hiring is still a human decision, and the personal impression you make matters.

This isn’t just about new grads

While our research focuses on early-career hiring, these findings apply to other audiences as well, such as career changers, returning professionals and even mid-career workers. These workers are increasingly being evaluated on their adaptability, behavior and collaborative ability – not just their experience.

Many companies now offer project-based assignments and trial roles that let them evaluate performance before making a permanent hire.

At the same time, employers are investing in internal reskilling and upskilling programs. Reskilling refers to training workers for entirely new roles, often in response to job changes or automation, while upskilling means helping employees deepen their current skills to stay effective and advance in their existing roles. Our report indicates that approximately 88% of large companies now offer structured upskilling and reskilling programs. For job seekers and workers alike, staying competitive means taking the initiative and demonstrating a commitment to learning and growth.

Show up early, and show up well

So what can students, or anyone entering or reentering the workforce, do to prepare?

-

Start early. Don’t wait until senior year. First- and second-year internships are growing in importance.

-

Sharpen your soft skills. Communication, time management, problem-solving and ethical behavior are top priorities for employers.

-

Understand where work is happening. Over 50% of entry-level jobs are fully in-person. Only 4% are fully remote. Show up ready to engage.

-

Use AI strategically. It’s a useful tool for research and practice, not a shortcut to connection or clarity.

-

Stay curious. Most large employers now offer reskilling or upskilling opportunities – and they expect employees to take initiative.

One of the clearest takeaways from this year’s report is that hiring is no longer a one-time decision. It’s a performance process that often begins before an interview is even scheduled.

Whether you’re still in school, transitioning in your career or returning to the workforce after a break, the same principle applies: Every opportunity is an audition. Treat it like one.

![]()

Murugan Anandarajan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Companies haven’t stopped hiring, but they’re more cautious, according to the 2025 College Hiring Outlook Report – https://theconversation.com/companies-havent-stopped-hiring-but-theyre-more-cautious-according-to-the-2025-college-hiring-outlook-report-257870