Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Rodney Coates, Professor of Critical Race and Ethnic Studies, Miami University

Few issues in the U.S. today are as controversial as diversity, equity and inclusion – commonly referred to as DEI.

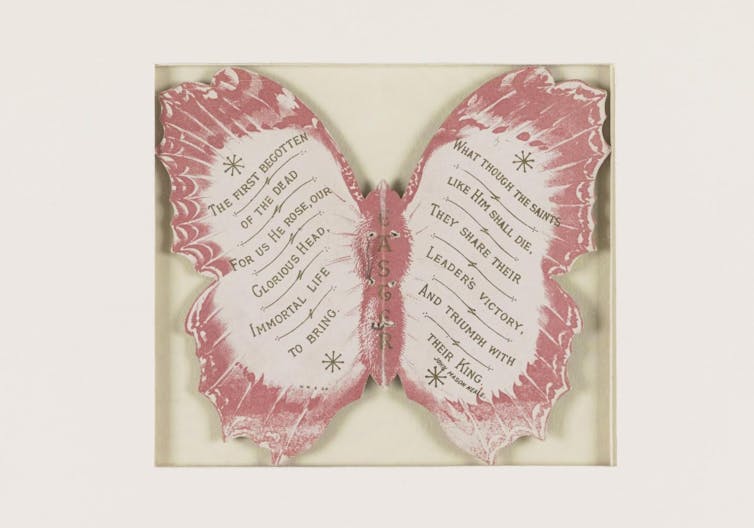

Although the term didn’t come into common usage until the 21st century, DEI is best understood as the latest stage in a long American project. Its egalitarian principles are seen in America’s founding documents, and its roots lie in landmark 20th-century efforts such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and affirmative action policies, as well as movements for racial justice, gender equity, disability rights, veterans and immigrants.

These movements sought to expand who gets to participate in economic, educational and civic life. DEI programs, in many ways, are their legacy.

Critics argue that DEI is antidemocratic, that it fosters ideological conformity and that it leads to discriminatory initiatives, which they say disadvantage white people and undermine meritocracy. Those defending DEI argue just the opposite: that it encourages critical thinking and promotes democracy − and that attacks on DEI amount to a retreat from long-standing civil rights law.

Yet missing from much of the debate is a crucial question: What are the tangible costs and benefits of DEI? Who benefits, who doesn’t, and what are the broader effects on society and the economy?

As a sociologist, I believe any productive conversation about DEI should be rooted in evidence, not ideology. So let’s look at the research.

Who gains from DEI?

In the corporate world, DEI initiatives are intended to promote diversity, and research consistently shows that diversity is good for business. Companies with more diverse teams tend to perform better across several key metrics, including revenue, profitability and worker satisfaction.

Businesses with diverse workforces also have an edge in innovation, recruitment and competitiveness, research shows. The general trend holds for many types of diversity, including age, race and ethnicity, and gender.

A focus on diversity can also offer profit opportunities for businesses seeking new markets. Two-thirds of American consumers consider diversity when making their shopping choices, a 2021 survey found. So-called “inclusive consumers” tend to be female, younger and more ethnically and racially diverse. Ignoring their values can be costly: When Target backed away from its DEI efforts, the resulting backlash contributed to a sales decline.

But DEI goes beyond corporate policy. At its core, it’s about expanding access to opportunities for groups historically excluded from full participation in American life. From this broader perspective, many 20th-century reforms can be seen as part of the DEI arc.

Consider higher education. Many elite U.S. universities refused to admit women until well into the 1960s and 1970s. Columbia, the last Ivy League university to go co-ed, started admitting women in 1982. Since the advent of affirmative action, women haven’t just closed the gender gap in higher education – they outpace men in college completion across all racial groups. DEI policies have particularly benefited women, especially white women, by expanding workforce access.

Similarly, the push to desegregate American universities was followed by an explosion in the number of Black college students – a number that has increased by 125% since the 1970s, twice the national rate. With college gates open to more people than ever, overall enrollment at U.S. colleges has quadrupled since 1965. While there are many reasons for this, expanding opportunity no doubt plays a role. And a better-educated population has had significant implications for productivity and economic growth.

The 1965 Immigration Act also exemplifies DEI’s impact. It abolished racial and national quotas, enabling the immigration of more diverse populations, including from Asia, Africa, southern and eastern Europe and Latin America. Many of these immigrants were highly educated, and their presence has boosted U.S. productivity and innovation.

Ultimately, the U.S. economy is more profitable and productive as a result of immigrants.

What does DEI cost?

While DEI generates returns for many businesses and institutions, it does come with costs. In 2020, corporate America spent an estimated US$7.5 billion on DEI programs. And in 2023, the federal government spent more than $100 million on DEI, including $38.7 million by the Department of Health and Human Services and another $86.5 million by the Department of Defense.

The government will no doubt be spending less on DEI in 2025. One of President Donald Trump’s first acts in his second term was to sign an executive order banning DEI practices in federal agencies – one of several anti-DEI executive orders currently facing legal challenges. More than 30 states have also introduced or enacted bills to limit or entirely restrict DEI in recent years. Central to many of these policies is the belief that diversity lowers standards, replacing meritocracy with mediocrity.

But a large body of research disputes this claim. For example, a 2023 McKinsey & Company report found that companies with higher levels of gender and ethnic diversity will likely financially outperform those with the least diversity by at least 39%. Similarly, concerns that DEI in science and technology education leads to lowering standards aren’t backed up by scholarship. Instead, scholars are increasingly pointing out that disparities in performance are linked to built-in biases in courses themselves.

That said, legal concerns about DEI are rising. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Department of Justice have recently warned employers that some DEI programs may violate Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Anecdotal evidence suggests that reverse discrimination claims, particularly from white men, are increasing, and legal experts expect the Supreme Court to lower the burden of proof needed by complainants for such cases.

The issue remains legally unsettled. But while the cases work their way through the courts, women and people of color will continue to shoulder much of the unpaid volunteer work that powers corporate DEI initiatives. This pattern raises important equity concerns within DEI itself.

What lies ahead for DEI?

People’s fears of DEI are partly rooted in demographic anxiety. Since the U.S. Census Bureau projected in 2008 that non-Hispanic white people would become a minority in the U.S by the year 2042, nationwide news coverage has amplified white fears of displacement.

Research indicates many white men experience this change as a crisis of identity and masculinity, particularly amid economic shifts such as the decline of blue-collar work. This perception aligns with research showing that white Americans are more likely to believe DEI policies disadvantage white men than white women.

At the same time, in spite of DEI initiatives, women and people of color are most likely to be underemployed and living in poverty regardless of how much education they attain. The gender wage gap remains stark: In 2023, women working full time earned a median weekly salary of $1,005 compared with $1,202 for men − just 83.6% of what men earned. Over a 40-year career, that adds up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost earnings. For Black and Latina women, the disparities are even worse, with one source estimating lifetime losses at $976,800 and $1.2 million, respectively.

Racism, too, carries an economic toll. A 2020 analysis from Citi found that systemic racism has cost the U.S. economy $16 trillion since 2000. The same analysis found that addressing these disparities could have boosted Black wages by $2.7 trillion, added up to $113 billion in lifetime earnings through higher college enrollment, and generated $13 trillion in business revenue, creating 6.1 million jobs annually.

In a moment of backlash and uncertainty, I believe DEI remains a vital if imperfect tool in the American experiment of inclusion. Rather than abandon it, the challenge now, from my perspective, is how to refine it: grounding efforts not in slogans or fear, but in fairness and evidence.

![]()

Rodney Coates does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Beyond the backlash: What evidence shows about the economic impact of DEI – https://theconversation.com/beyond-the-backlash-what-evidence-shows-about-the-economic-impact-of-dei-252143