Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Masha Remskar, Psychologist and Postdoctoral Researcher in Behavioral Science, Arizona State University

Most people know roughly what kind of lifestyle they should be living to stay healthy.

Think regular exercise, a balanced diet and sufficient sleep. Yet, despite all the hacks, trackers and motivational quotes, many of us still struggle to stick with our health goals.

Meanwhile, people worldwide are experiencing more lifestyle-associated chronic disease than ever before.

But what if the missing piece in your health journey wasn’t more discipline – but more stillness?

Research shows that mindfulness meditation can help facilitate this pursuit of health goals through stillness, and that getting started is easier than you might think – no Buddhist monk robes or silent retreats required.

Given how ubiquitous and accessible mindfulness resources are these days, I have been surprised to see mindfulness discussed and studied only as a mental health tool, stopping short of exploring its usefulness for a whole range of lifestyle choices.

I am a psychologist and behavioral scientist researching ways to help people live healthier lives, especially by moving more and regulating stress more efficiently.

My team’s work and that of other researchers suggests that mindfulness could play a pivotal role in paving the way for a healthier society, one mindful breath at a time.

Mindfulness unpacked

Mindfulness has become a buzzword of late, with initiatives now present in schools, boardrooms and even among first responders. But what is it, really?

Mindfulness refers to the practice or instance of paying careful attention to one’s present-moment experience – such as their thoughts, breath, bodily sensations and the environment – and doing so nonjudgmentally. Its origins are in Buddhist traditions, where it plays a crucial role in connecting communities and promoting selflessness.

Over the past 50 years, however, mindfulness-based practice has been Westernized into structured therapeutic programs and stress-management tools, which have been widely studied for their benefits to mental and physical health.

Research has shown that mindfulness offers wide-ranging benefits to the mind, the body and productivity.

Mindfulness-based programs, both in person and digitally delivered, can effectively treat depression and anxiety, protect from burnout, improve sleep and reduce pain.

The impacts extend beyond subjective experience too. Studies find that experienced meditators – that is, people who have been meditating for at least one year – have lower markers of inflammation, which means that their bodies are better able to fight off infections and regulate stress. They also showed improved cognitive abilities and even altered brain structure.

But I find the potential for mindfulness to support a healthy lifestyle most exciting of all.

Maria Korneeva/Moment via Getty Images

How can mindfulness help you build healthy habits?

My team’s research suggests that mindfulness equips people with the psychological skills required to successfully change behavior. Knowing what to do to achieve healthy habits is rarely what stands in people’s way. But knowing how to stay motivated and keep showing up in the face of everyday obstacles such as lack of time, illness or competing priorities is the most common reason people fall off the wagon – and therefore need the most support. This is where mindfulness comes in.

Multiple studies have found that people who meditate regularly for at least two months become more inherently motivated to look after their health, which is a hallmark of those who adhere to a balanced diet and exercise regularly.

A 2024 study with over 1,200 participants that I led found more positive attitudes toward healthy habits and stronger intentions to put them into practice in meditators who practiced mindfulness for 10 minutes daily alongside a mobile app, compared with nonmeditators. This may happen because mindfulness encourages self-reflection and helps people feel more in tune with their bodies, making it easier to remember why being healthier is important to us.

Another key way mindfulness helps keep momentum with healthy habits is by restructuring one’s response to pain, discomfort and failure. This is not to say that meditators feel no pain, nor that pain during exercise is encouraged – it is not!

Mild discomfort, however, is a very common experience of novice exercisers. For example, you may feel out of breath or muscle fatigue when initially taking up a new activity, which is when people are most likely to give up. Mindfulness teaches you to notice these sensations but see them as transient and with minimal judgment, making them less disruptive to habit-building.

Putting mindfulness into practice

A classic mindfulness exercise includes observing the breath and counting inhales up to 10 at a time. This is surprisingly difficult to do without getting distracted, and a core part of the exercise is noticing the distraction and returning to the counting. In other words, mindfulness involves the practice of failure in small, inconsequential ways, making real-world perceived failure – such as a missed exercise session or a one-off indulgent meal – feel more manageable. This strengthens your ability to stay consistent in pursuit of health goals.

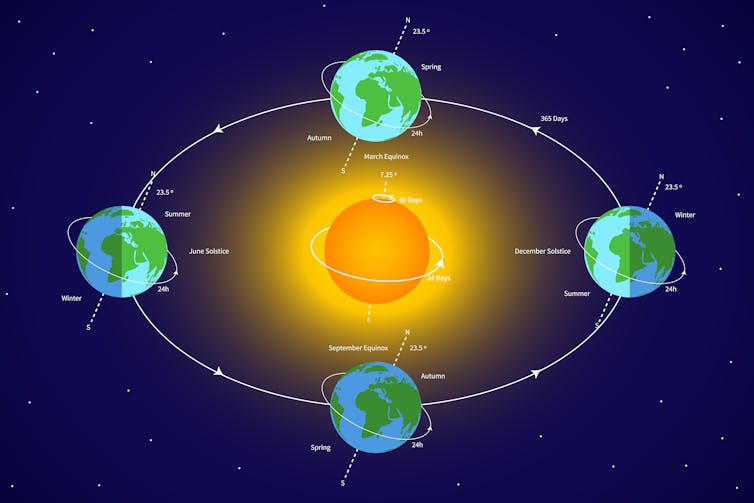

Finally, paying mindful attention to our bodies and the environment makes us more observant, resulting in a more varied and enjoyable exercising or eating experience. Participants in another study we conducted reported noticing the seasons changing, a greater connection to their surroundings and being better able to detect their own progress when exercising mindfully. This made them more likely to keep going in their habits.

Luckily, there are plenty of tools available to get started with mindfulness practice these days, many of them free. Mobile applications, such as Headspace or Calm, are popular and effective starting points, providing audio-guided sessions to follow along. Some are as short as five minutes. Research suggests that doing a mindfulness session first thing in the morning is the easiest to maintain, and after a month or so you may start to see the skills from your meditative practice reverberating beyond the sessions themselves.

Based on our research on mindfulness and exercise, I collaborated with the nonprofit Medito Foundation to create the first mindfulness program dedicated to moving more. When we tested the program in a research study, participants who meditated alongside these sessions for one month reported doing much more exercise than before the study and having stronger intentions to keep moving compared with participants who did not meditate. Increasingly, the mobile applications mentioned above are offering mindful movement meditations too.

If the idea of a seated practice does not sound appealing, you can instead choose an activity to dedicate your full attention to. This can be your next walk outdoors, where you notice as much about your experience and surroundings as possible. Feeling your feet on the ground and the sensations on your skin are a great place to start.

For people with even less time available, short bursts of mindfulness can be incorporated into even the busiest of routines. Try taking a few mindful, nondistracted breaths while your coffee is brewing, during a restroom break or while riding the elevator. It may just be the grounding moment you need to feel and perform better for the rest of the day.

![]()

Masha Remskar previously received funding from UK Research & Innovation’s Economic and Social Research Council, and served as Head of Science at the Medito Foundation. The Medito Foundation is a non-profit that does not benefit financially from users downloading and using its mobile app.

– ref. Mindfulness won’t burn calories, but it might help you stick with your health goals – https://theconversation.com/mindfulness-wont-burn-calories-but-it-might-help-you-stick-with-your-health-goals-260482