Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Evelyn Valdez-Ward, Postdoctoral Fellow in Science Communication, University of Rhode Island

Lived experiences shape how science is conducted. This matters because who gets to speak for science steers which problems are prioritized, how evidence is translated into practice and who ultimately benefits from scientific advances. For researchers whose communities have not historically been represented in science – including many people of color, LGBTQ+ and first-generation scientists – identity is intertwined with how they engage in and share their work.

As researchers who ourselves belong to communities that have been underrepresented in science, we work with scientists from marginalized backgrounds to study how they navigate STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – spaces. What happens when sharing science with the public is treated as relationship-building rather than a one-way transfer of information? We want to understand the role that identity plays in building community in science.

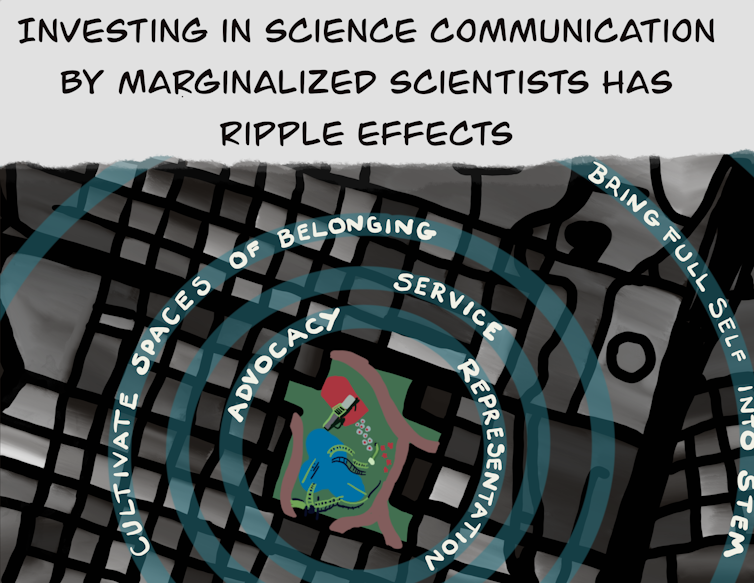

We found that broadening the ways scientists work with the public can bolster trust in science, expand who feels they belong in STEM spaces and ensure that science is working in service of community needs.

STEM spaces as an obstacle course

Science communication involves bridging knowledge gaps between scientists and the broader community. Traditionally, researchers do it through public lectures, media interviews, press releases, social media posts or outreach events designed to explain science in simpler terms. The goals of these activities are often to correct misconceptions, increase scientific literacy and encourage the general public to trust scientific institutions.

However, science communication can look different for researchers from marginalized backgrounds. For these scientists, the ways they engage with the public often focus on identity and belonging. The researchers we interviewed spoke about hosting bilingual workshops with local families, creating comics about climate change with Indigenous youth and starting podcasts where scientists of color share their pathways into STEM.

Instead of disseminating science information through traditional methods that leave little room for dialogue, these researchers seek to bring science back to their communities. This is in part because scientists from historically marginalized backgrounds often face hostile environments in STEM, including discrimination, stereotypes about their competence, isolation and a lack of representation in their fields. Many of the researchers we talked to described feeling pressure to hide aspects of their identities, being seen as the token minority, or having to constantly prove they belong. These experiences reflect well-documented structural barriers in STEM that shape who feels welcome and supported in scientific environments.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND

We wanted to see if a broader definition of science communication that incorporates identity as an asset can expand who feels welcomed in scientific spaces, strengthen trust between scientists and communities, and ensure scientific knowledge is shared in culturally relevant and accessible ways.

Transforming STEM communication

Prior studies have found that scientists tend to prioritize communication focused on conveying information, placing much less emphasis on understanding audiences, building trust or fostering dialogue. Our research, however, suggests that marginalized scientists adopt communication styles that are more inclusive.

Our team set out to create training spaces for researchers from communities that have been historically marginalized in science. Since 2018, we have been facilitating ReclaimingSTEM workshops both in-person and online, where over 700 participants have been encouraged to explore the intersections of their identities and science through interactive modules, small-group activities and community-building discussions.

Expanding what counts as science communication is essential for it to be effective. This is particularly relevant for scientists whose work and identities call for approaches grounded in community connection, cultural relevance and reciprocity. In our workshops, we broadly defined science communication as community engagement about science that could be both formal and informal, including through media, art, music, podcasts and outreach in schools, among others.

While some participants mentioned using traditional science communication approaches – like making topics concise and clear, as well as avoiding jargon – most used communication styles and methods that are more audience-centered, identity-focused and emotion-driven.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND

Some participants drew on their audience’s cultural backgrounds when sharing their research. One participant described explaining biological pattern formation by connecting it to familiar artistic traditions in her community, such as the geometric and floral designs used in henna. Using imagery that her audience recognized helped make the scientific concepts more relatable and encouraged deeper engagement.

Rather than portray science as something neutral or emotionless, participants infused empathy and feeling into their community engagement. For example, one scientist shared with us that his experiences of exclusion as a multiracial gay man shaped how he approached his interactions. These feelings helped him be more patient, understanding and attentive when others struggled to grasp scientific ideas. By drawing on his own sense of not belonging, he aimed to create an environment where people could connect emotionally to his research and feel supported in the learning process.

Participants found it important to incorporate their identities into their communication styles. For some, this meant not assimilating into the dominant norms of science spaces and instead authentically expressing their identities to be a role model to others. For example, one participant explained that openly identifying as disabled helped normalize that experience for others.

Many felt a deep sense of responsibility to have their science engagement be of service to their communities. One scientist who identified as a Black woman said she often thinks about how her research may affect people of color, and how to communicate her findings in ways that everyone can understand and benefit from.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND

Making STEM more inclusive

While the participants of our workshop had a variety of goals when it came to science communication, a common thread was their desire to build a sense of belonging in STEM.

We found that marginalized scientists often draw on their lived experiences and community connections when teaching and speaking about their research. Other researchers have also found that these more inclusive approaches to science communication can help build trust, create emotional resonance, improve accessibility and foster a stronger sense of belonging among community members.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND

Centering the perspectives and identities of marginalized researchers would make science communication training programs more inclusive and responsive to community needs. For example, some participants described tailoring their science outreach to audiences with limited English proficiency, particularly within immigrant communities. Others emphasized communicating science in culturally relevant ways to ensure information is accessible to people in their home communities. Several also expressed a desire to create welcoming and inclusive spaces where their communities could see themselves represented and supported in STEM.

One scientist who identified as a disabled woman shared that accessibility and inclusivity shape her language and the information she communicates. Rather than talking about her research, she said, her goal has been more about sharing the so-called hidden curriculum for success: the unwritten norms, strategies and knowledge key to secure opportunities, and thrive in STEM.

Identity for science communication

Identity is central to how scientists navigate STEM spaces and how they communicate science to the audiences and communities they serve.

For many scientists from marginalized backgrounds, the goal of science communication is to advocate, serve and create change in their communities. The participants in our study called for a more inclusive vision of science communication: one grounded in identity, storytelling, community and justice. In the hands of marginalized scientists, science communication becomes a tool for resistance, healing and transformation. These shifts foster belonging, challenge dominant norms and reimagine STEM as a space where everyone can thrive.

Helping scientists bring their whole selves into how they choose to communicate can strengthen trust, improve accessibility and foster belonging. We believe redesigning science communication to reflect the full diversity of those doing science can help build a more just and inclusive scientific future.

![]()

Evelyn Valdez-Ward is executive director of ReclaimingSTEM Institute.

Nic Bennett is a volunteer board member of Reclaiming STEM and People’s Science Network.

Robert N. Ulrich is the Associate Director of the ReclaimingSTEM Institute.

– ref. Science is best communicated through identity and culture – how researchers are ensuring STEM serves their communities – https://theconversation.com/science-is-best-communicated-through-identity-and-culture-how-researchers-are-ensuring-stem-serves-their-communities-246475