Source: The Conversation – UK – By Mark Sutton, Honorary Professor in the School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh

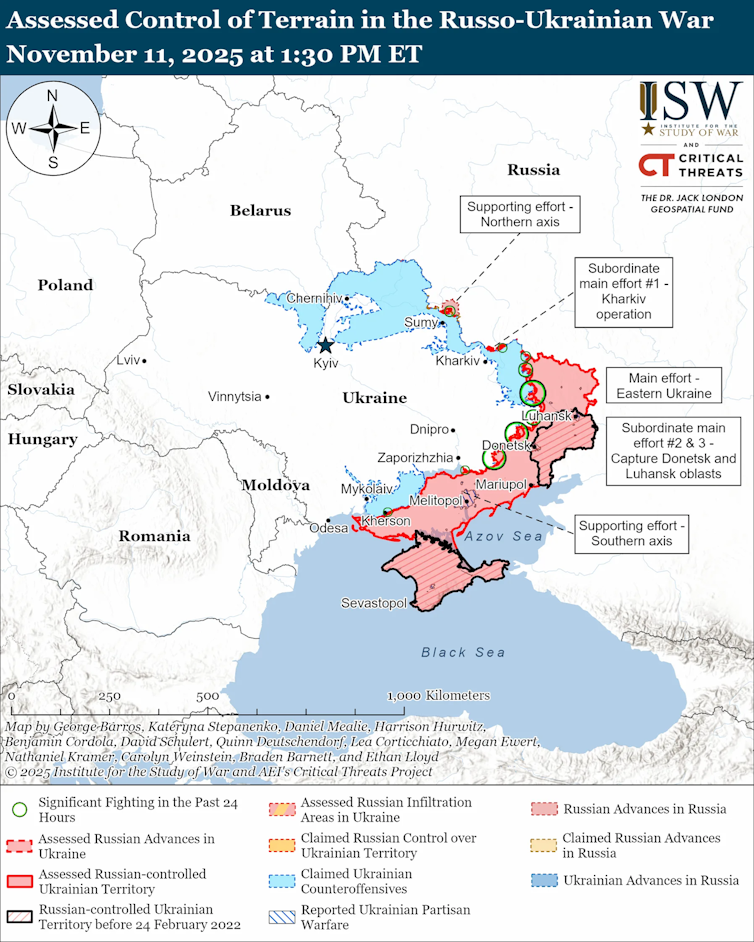

For decades, Ukraine was known as the breadbasket of the world. Before the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, it ranked among the top global producers and exporters of sunflower oil, maize and wheat. These helped feed more than 400 million people worldwide.

But beyond the news about grain blockades lies a deeper, slower-moving crisis: the depletion of the very nutrients that make Ukraine’s fertile black soil so productive.

While the ongoing war has focused global attention on Ukraine’s food supply chains, far less is known about the sustainability of the agricultural systems that underpin them.

Ukraine’s soil may no longer be able to sustain the country’s role as one of the major food producers without urgent action. And this could have consequences that stretch far beyond its borders.

In our research, we have examined nutrient management in Ukrainian agriculture over the past 40 years and found a dramatic reversal of nutrient levels.

During the Soviet era, Ukraine’s farmland was excessively fertilised. Nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium were applied at levels far beyond what crops could absorb. This led to pollution of the air and water.

But since independence in 1991, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Fertiliser use, especially phosphorus and potassium, plummeted as imports fell, livestock numbers declined (reducing manure availability) and supply chains collapsed.

By 2021, just before the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian soil was already showing signs of strain. Farmers were adding much less phosphorus and potassium than the crops were taking up, around 40–50% less phosphorus and 25% less potassium, and the soil’s organic matter had dropped by almost 9% since independence.

In many regions, farmers applied too much nitrogen, but often too little phosphorus and potassium to maintain long-term fertility. Moreover, although livestock numbers have declined significantly over the past decades, our analysis shows that about 90% of the manure still produced is wasted. This is equivalent to roughly US$2.2 billion (£1.6 billion) in fertiliser value each year.

These nutrient imbalances are not just a national issue. They threaten Ukraine’s long-term agricultural productivity and, by extension, the global food supply that depends on it.

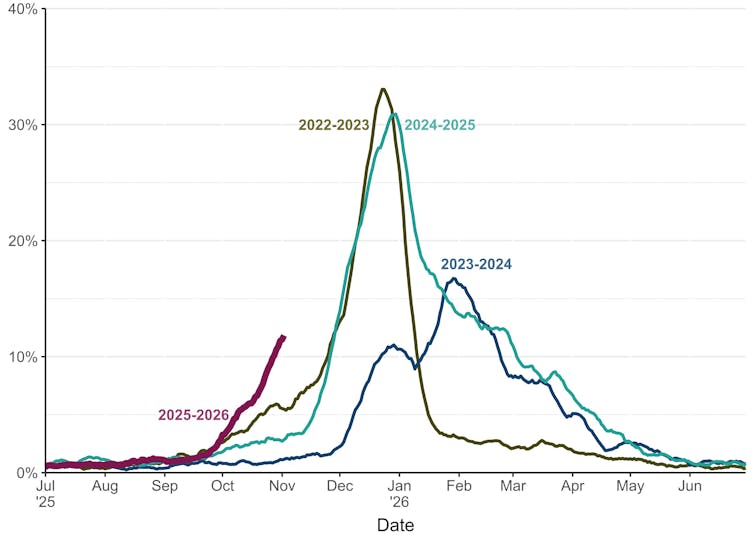

The war has sharply intensified the problem. Russia’s invasion has disrupted fertiliser supply chains and damaged storage facilities. Fertiliser prices have soared. Many farmers deliberately applied less fertiliser in 2022-2023 to reduce financial risks, knowing that their harvests could be destroyed, stolen or left unsold due to blocked export routes.

Our new research shows alarming trends across the country. In 2023, harvested crops took up to 30% more nitrogen, 80% more phosphorus and 70% more potassium from the soil than they received through fertilisation, soil microbes and from the air (including what comes down in rain and what settles onto the ground from the air).

If these trends continue, Ukraine’s famously fertile soil could face lasting degradation, threatening the country’s capacity to recover and supply global food markets once peace returns.

Rebuilding soil fertility

Some solutions exist and many are feasible even during wartime. Our research team has developed a plan for Ukrainian farmers that could quickly make a difference. These measures could substantially improve nutrient use efficiency and reduce wasted nutrients, keeping farms productive and profitable, while reducing soil degradation and environmental pollution.

These proposed solutions include:

-

Precision fertilisation – applying fertilisers at the right time, place and amount to match crop needs efficiently

-

Enhanced manure use – setting up local systems to collect surplus manure and redistribute it to other farms, reducing dependence on (imported) synthetic fertilisers

-

Improved fertiliser use – applying enhanced-efficiency fertilisers that release nutrients slowly, reducing losses to air and water

-

Planting legumes (such as peas or soybeans) – including these in crop rotations, improves soil health while adding nitrogen naturally

Some of these actions require investment, such as better facilities for storage, treatment and better application of manure to fields, but many can be rolled out, at least partially, without too much extra funding.

Ukraine’s recovery fund, backed by the World Bank to help Ukraine after the war ends, includes support for agriculture, and this could play a key role here.

Why it matters beyond Ukraine

Ukraine’s nutrient crisis is a warning for the world. Intensive, unbalanced farming, whether through overuse, under use or misuse of fertilisers, is unsustainable. Nutrient mismanagement contributes to both food insecurity and environmental pollution.

Our research is part of the forthcoming International Nitrogen Assessment, which highlights the need for effective global nitrogen management and showcases practical options to maximise the multiple benefits of better nitrogen use – improved food security, climate resilience, and water and air quality.

In the rush to ensure cheap food and stable exports, we must not overlook the foundations of long-term agricultural productivity: healthy, fertile soils.

Supporting Ukraine’s farmers offers a chance not only to rebuild a nation but also to change global agriculture to help create a more resilient, sustainable future.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Prof. Mark Sutton works for the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, based at its Edinburgh Research Station. He is an honorary professor at the University of Edinburgh, School of Geosciences. He receives funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through its Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), the UK Department for Environment and Rural Affairs (Defra), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF). He is Director of the International Nitrogen Management System (INMS) funded by GEF/UNEP, and of the GCRF South Asian Nitrogen Hub. He is co-chair of the UNECE Task Force on Reactive Nitrogen (TFRN) and of the Global Partnership on Nutrient Management (GPNM) which is convened by UNEP.

Sergiy Medinets receives funding from UKRI, Defra, DAERA, British Academy, UNEP, GEF, UNDP and EU

– ref. Ukraine’s farms once fed billions but now its soil is starving – https://theconversation.com/ukraines-farms-once-fed-billions-but-now-its-soil-is-starving-269147