Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Amani Braa, Assistant lecturer, Université de Montréal

In 2025, youth-led protests erupted everywhere from Morocco to Nepal, Madagascar and Europe. A generation refused to remain silent in the face of economic precariousness, corruption and eroding democratic norms and institutions.

Although they arose in different contexts, all the protests were met with the same playbook of responses: repression, contempt and suspicion towards youth dismissed as irresponsible.

Mobilization across several continents

In Morocco, the #Gen212 movement, which originated on social media, denounced the high cost of living, police violence, muzzling of civil society and lack of opportunities. This mobilization, which began digitally on platforms such as Discord, quickly spilled over from screens into concrete action taken in several cities across the country.

In Madagascar, young people took to the streets at the end of September in a climate of high pre-election tensions to demand real change before being violently repressed. In Nepal, thousands of young people occupyied public spaces, demanding genuine democracy and an end to the corruption that is undermining the country.

À lire aussi :

Gen Z protests brought about change in Nepal via the powers — and perils — of social media

In Europe, too, youth are mobilizing against authoritarian excesses and persistent inequalities. In Italy, France, and Spain, young people are taking to the streets to protest gender-based violence, unpopular reforms and police repression and to demand recognition of their political rights.

Although the contexts are very different, these mobilizations share the same goal of refusing injustice and demanding that marginalized voices be heard.

Authorities call youth immature and irrational

These movements are often treated as fleeting emotional outbursts, even though they express structured political demands for social justice, freedom, economic security, access to dignity and participation.

Yet the responses by governments have been heading in a totally different direction — towards increased repression. Young protesters are being monitored, arrested, stigmatized and sometimes accused of treason or of being manipulated by foreign powers.

In Morocco, for example, nearly 2,500 young people have been prosecuted, with more than 400 convicted — including 76 minors — since September 2025. The charges include “group rebellion,” “incitement to commit crimes” and participating in armed gatherings. More than 60 prison sentences have been handed down, some of them for up to 15 years.

This mass judicialization of a peaceful movement has been denounced by Amnesty International, which points to excessive uses of force and the increasing criminalization of protest.

In Madagascar, the response was just as brutal: at least 22 deaths, more than 100 injuries and hundreds of arbitrary arrests were recorded during youth demonstrations against corruption and electoral irregularities.

According to the United Nations, security forces used rubber bullets and tear gas to disperse the crowds. The crisis culminated in the flight of President Andry Rajoelina, which confirmed that, far from defusing the conflict, the crackdown revealed institutions’ fragility in the face of politicized youth.

À lire aussi :

Coups in Africa: how democratic failings help shape military takeovers – study

A discourse referring to parental responsibility

The actions of the young people who have been arrested during recent protests are often attributed to lack of parental responsibility.

In Morocco, for example, the Home Office has called on parents to supervise and guide their children. In Indonesia, the Philippines, Peru and Nepal alike, authorities call on parents to supervise, guide or restrain their children, shifting the political conflict into the family sphere.

This trend illustrates what national security researcher Fatima Ahdash calls the “familialization” of politics: instead of addressing the social, economic and ideological causes of protests, governments turn them into a matter of home education, depoliticizing, individualizing and privatizing the protests in the process. Families become the prism through which young people’s political behaviour is interpreted, evaluated and sometimes punished.

This response isn’t new, but it’s taking on unprecedented proportions in a global context of democratic fragility and authoritarian recentring of power marked by the restriction of freedoms, the control of protest and the criminalization of social movements.

States are adopting a defensive stance, treating youth engagement not as a civic resource but as a threat to be neutralized. This hardened stance is symptomatic of a deeper problem: youth are refusing to be satisfied with empty promises and forced compromises, but they face powers unable to recognize the legitimacy of their anger and aspirations..

Silencing criticism

Repression in response to criticism has become a tactic governments use to avoid being questioned. But this strategy is becoming increasingly fragile.

That’s because first, it denies the legitimacy of the anger being expressed. Secondly, it ignores a fundamental reality: that this anger is rooted in collective experiences of social decline, discrimination and political powerlessness. It’s not empty anger. It expresses a demand for social, political and environmental change that institutions are struggling to grasp.

Unlike mobilizations likr the Arab Spring of 2011, the current protests led by Generation Z are horizontal; they are decentralized, have no identifiable leaders, and are rooted in the urgency of the present.

They also originate on social media, organize themselves into autonomous micro-cells, reject structuring ideological narratives, and favour a politics of everyday life — meaning they reject precariousness while calling for immediate dignity and concrete justice.

Their esthetic is fluid, borrowing from digital codes — memes, manga, visual remixes — and their forms circulate through emotional affinities rather than imitation. This makes them elusive to the powers that be, but powerfully viral.

These movements stir up political emotions (anger, but also hope) and create new languages, digital practices and forms of engagement that often lie outside traditional parties.

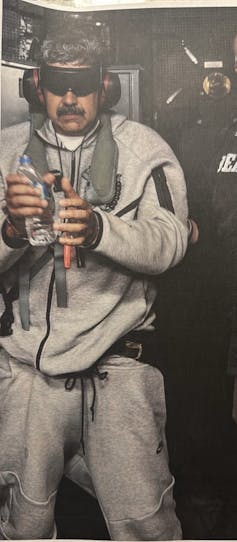

One unifying visual element keeps coming up: the black flag with a skull and crossbones wearing a straw hat, a symbol taken from the manga One Piece. More than just a nod to pop culture, this Jolly Roger embodies a thirst for justice, freedom and rebellion shared by a globalized youth, from Kathmandu to Rome.

In Serbia, for example, a student uprising in early 2025 with no visible leader united thousands of people around a simple slogan: more democracy. The movement spread to other generations, without any party or hierarchy, challenging a government that tried to stifle the protests through force and stigmatization.

Evading censorship

Meanwhile, the young people of Cuba Decide are mobilizing on digital platforms to demand a democratic referendum in the midst of constant surveillance. Thanks to encrypted tools and alliances abroad, they are circumventing censorship and amplifying their voices beyond borders.

While criminalizing young people and their protests may slow their momentum, it doesn’t solve anything. It only undermines the social contract, fuels political disenchantment and reinforces polarization. What’s more, it risks pushing demands for reform to outright refusal of the status quo.

Recent protests remind us of an obvious fact: young people are not “the future,” but political entities in the present. Governments need to hear not just the noise of protest, but the clarity of the demands: justice, dignity, representation and a future.

![]()

Amani Braa received funding from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Sociétés et Culture (FRQ-SC).

– ref. From Kathmandu to Casablanca, a generation under surveillance is rising up – https://theconversation.com/from-kathmandu-to-casablanca-a-generation-under-surveillance-is-rising-up-270624