Source: The Conversation – Africa – By Malyn Newitt, Emeritus Professor in History, King’s College London

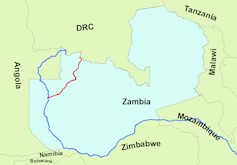

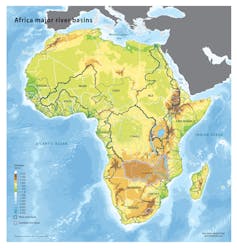

The Zambezi is Africa’s fourth longest river, flowing through six countries: Angola, Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, where it becomes the largest river to flow into the Indian Ocean.

The entire length of the river is referred to as the Zambezi Valley region and it carries with it a rich history of movement, conquest and commerce.

Great Britain colonised Zambia, Botswana and Zimbabwe; Germany colonised Namibia. The beginning and the end of the Zambezi, in Angola and Mozambique, were Portuguese colonies.

Malyn Newitt is a historian of Portuguese colonialism in Africa and has written numerous books on the subject, and one on the Zambezi in particular. We asked him about this history.

When and how did the Portuguese encounter the Zambezi?

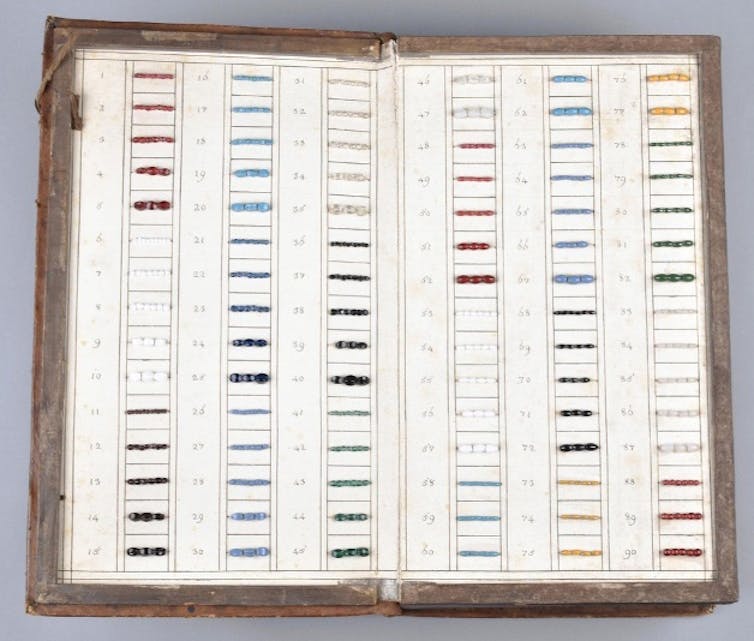

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish permanent relations with the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa. After the explorer Vasco da Gama’s successful return voyage from Europe to India (1497-1499) the Portuguese heard about the gold trade being carried on in the ports of the Zambezi River. By the middle of the 1500s they were trading there, from their bases on the coast of modern Mozambique. From Sofala and Mozambique Island, they sent agents to the gold trading fairs inland.

MellonDor, CC BY-SA

Between 1569 and 1575 a Portuguese military expedition tried to conquer the gold producing regions of what became known as Mashonaland (today part of Zimbabwe). This failed, but permanent settlements were made in the Zambezi valley from which Portuguese control was gradually extended over the river up to the Cahora Bassa gorge in modern Mozambique.

Portuguese adventurers, with their locally recruited private armies, began to control large semi-feudal land holdings known as prazos. These reached their greatest extent in the mid-1600s.

GRID-Arendal, CC BY-NC-SA

During the 1700s and early 1800s the area of Portuguese control was limited to the Zambezi valley. Here the elite of Afro-Portuguese prazo holders traded gold and slaves.

The first half of the 1800s saw drought, the migrations of the Nguni (spurred by Zulu-led wars in southern Africa) and the continuing slave trade. During these disturbed conditions, Afro-Portuguese warlords raised private armies and extended their control up the river. They went as far as Kariba (on the border between modern Zambia and Zimbabwe) and through much of the escarpment country north and south of the river.

This eventually brought them into conflict with Britain, whose agents were expanding their activities from South Africa. It resulted in an 1891 agreement which drew the frontiers in and around the Zambezi valley which still exist today.

Who are the people who live along the river?

The people who have inhabited the length of the Zambezi valley have often been generically referred to as Tonga. For the most part they’ve organised their lives in small, lineage-based settlements. Their economy is based on crop growing and occupations relating to trade and navigation on the river.

Because of the lack of any centralised political organisation, the valley communities were often dominated by the powerful kingdoms on the north and south of the river. This might involve raiding and enslavement or simply paying tribute to the kings. On the upper reaches of the river in Zambia, populations became subject to the large Barotse kingdom in the 1800s.

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA

On the lower river many of the people came under the overlordship of prazos. They worked as carriers, artisans, boatmen and soldiers. Because of the extensive gold and ivory trade, a fine tradition of goldsmith work developed and men became skilled elephant hunters.

Throughout history, valley communities have often been loosely organised around spirit shrines with mediums. These are very influential in providing stability and direction for people’s lives.

How did the Portuguese understand these cultures?

For 400 years the Portuguese controlled the lower reaches of the Zambezi, in Mozambique. They wrote many accounts of the people of the region which show a complex interaction. Portugal’s administration and system of land law controlled matters at the apex of society, but could not control African culture.

Discott, CC BY-NC-SA

The Portuguese were few in number and intermarried to some extent with the local population. This produced a hybrid Afro-Portuguese society in which everyday life was carried on according to African traditional practice. Agriculture, transport, artisan crafts, mining and warfare reflected local traditions.

Although the Portuguese tried to introduce Christianity, it failed to attract many people away from the spirit cults. It became diluted with local religious ideas.

The Portuguese built square, European-style houses in the river ports and on the estates along the river. But most of the population retained the traditional African hut design. Afro-Portuguese were often literate but literacy did not penetrate far and the Portuguese language never replaced the local languages.

How did silver play a role in all this?

Late in the 1500s the Portuguese became obsessed with the idea that there were silver mines in Africa comparable to those discovered by the Spanish in the New World. Considerable effort was made to locate these mines in Angola and in the Zambezi valley.

Read more:

The incredible journey of two princes from Mozambique whose lives were upended by the slave trade

Military expeditions were dispatched and skilled miners were sent from Europe to test the ores that had allegedly been discovered. Attempts to find the mines throughout the 1600s helped to sustain Portuguese interest in the Zambezi settlements. No silver was ever discovered – not surprisingly, as there is no silver in southern Africa.

Can you bring us up to today? What impact has development had on the river?

Until the 1900s the Zambezi defied most attempts at development. The river was difficult to navigate – too shallow in the dry season, too dangerous during the floods. These fluctuations determine the pattern of migrations and agricultural production.

Moreover, as the river passed through a series of gorges which blocked navigation it was only on its upper reaches, beyond the Victoria Falls, on the borders of Zimbabwe and Zambia, that it was able to act as a major highway.

And the river constituted a major obstacle to any contact between people north and south of it. The first bridge was only built in 1905, to carry the railway from South Africa to the copper belt. In the 1930s, British engineers built a second rail bridge across the lower Zambezi. But the first road bridge was only built in 1934, at Chirundu at the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe. This at last linked the areas north and south of the river.

Meanwhile the floods of the Zambezi came to be contained by the building of the Kariba Dam (opened in 1959) and the Cahora Bassa Dam (1974). As a result much of the Zambezi below the Victoria Falls has altered drastically and been turned into a succession of large inland seas.

Diego Delso, CC BY-NC-SA

Large sectors of the population have been forcibly removed and the floods no longer keep sea water from invading the delta. Meanwhile water extraction for irrigation, and increasingly frequent droughts, have endangered the river’s very existence.

The Zambezi has become an example of what happens when the natural resources of a great river have been thoughtlessly over-exploited.

![]()

Malyn Newitt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The history of the Zambezi River is a tale of culture, conquest and commerce – https://theconversation.com/the-history-of-the-zambezi-river-is-a-tale-of-culture-conquest-and-commerce-269217