Source: The Conversation – Africa – By Iwa Salami, Professor of Law, University of East London

A notification popped up on my LinkedIn the other day. Africans were doing a traditional celebratory dance at the Africa Stablecoin summit in Johannesburg.

The picture gave me a sinking feeling.

Why? While stablecoins can advance financial inclusion in Africa, could this celebration mark the potential transfer of monetary sovereignty from African economies to the economy issuing the most coveted currency-denominated stablecoin?

Stablecoins are crypto-assets or digital currencies designed to maintain a stable value, typically by being pegged to a reference asset such as a national currency (like US dollars), a commodity (like gold) or a basket of assets.

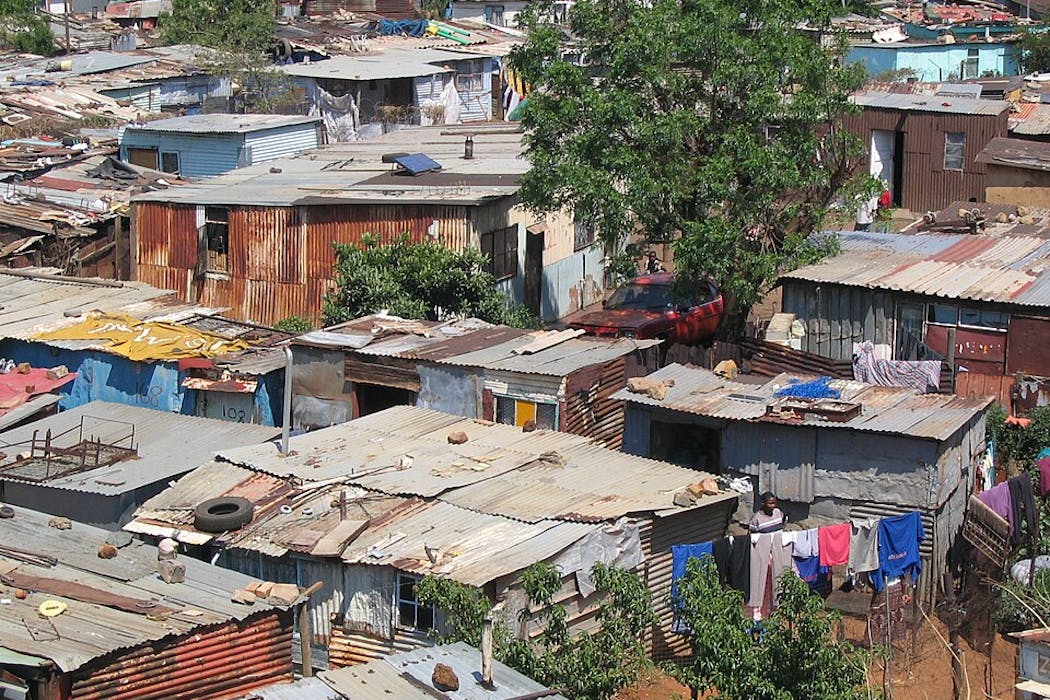

The use of stablecoins in Africa is on the rise, particularly in Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya. This rise is driven by currency volatility, inflation and limited access to stable foreign currency through traditional banking. Those problems prompt some people to adopt US dollar-denominated stablecoins for saving, hedging and remittances.

Part of their appeal is that they can be moved across borders more quickly, cheaply and efficiently than conventional assets. In South Africa, a well developed regulatory and financial infrastructure has increased institutional confidence, expanding stablecoin use beyond retail into business payments, remittances and other business-to-business transactions.

Their stability is usually achieved through reserves, collateral, or algorithmic mechanisms that prevent large price swings.

My book, Financial Technology Law and Regulation in Africa, looked at their operation as a crypto-asset in African states. I raised concerns about their potential impact on emerging economies, including African countries, in 2019 and 2020. A recent International Monetary Fund paper has echoed these concerns.

The journey so far

Stablecoins emerged in 2014 to reduce the volatility of crypto-assets for crypto-holders who wanted to cash out of a high-value crypto-asset before it crashed. Crypto-asset values crash easily because they are highly speculative, sentiment-driven, and can be sold instantly at scale, allowing fear to trigger rapid sell-offs.

The most popular ones are US dollar-denominated USDT and USDC issued by private companies Tether and Circle, respectively. However, stablecoins were unregulated for about 10 to 11 years before the EU Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) regulation in 2024 and the US Genius Act in 2025. During this period, there were no disclosure requirements governing these crypto-assets.

As not all are subject to regulation, criticisms abound regarding the quality and opaque nature of the assets backing them and their robustness to withstand redemption runs or large cash redemption by holders of stablecoins.

These criticisms arise as it is often unclear exactly how liquid, safe, and transparent the assets backing stablecoins are, raising doubts about whether unregulated issuers could meet large, sudden redemption demands without stress. This matters because the stablecoin market is worth approximately US$300 billion, so a loss of confidence could trigger mass redemptions and cause disruption well beyond the crypto-asset sector.

Potential problems

The rise in the use of stablecoins poses a risk of dollarisation, as US dollar-denominated stablecoins account for 99% of the stablecoin market. Dollarisation is the excessive use of the dollar in local African economies. It could be a threat to African states’ monetary sovereignty and drive capital flight from African economies.

To avert this problem, African authorities and central banks would first need to be prepared to impose restrictions or limits on the amounts of these US dollar or foreign-denominated stablecoins that can circulate within their economies at any given time. This is to prevent the threat to monetary sovereignty.

Secondly, African economies should also be prepared to put in place sound policy frameworks through which they can build credibility for their currencies and, therefore, avoid the risk of dollarisation.

Thirdly, they can consider launching their own stablecoins. This can be in the form of a local currency stablecoin or a regional stablecoin. To prevent capital flight from the economies, these stablecoins can be backed by a commodity or a basket of commodities, from Africa’s wealth of natural resources and minerals such as precious stones, gold, diamonds, crude oil and cobalt. To have a global edge, a dollar value can be derived from these commodities.

Since the proposed African backed stablecoin would be a local currency with a US dollar value, it could be used to settle domestic, regional and global transactions without the need for US dollars, whose backing assets are held outside the country and in the US.

Fourthly, they could also consider issuing their own retail central bank digital currency, as this would have exactly the same effect as fiat but in digital form. It would have the same credibility status as fiat, which would need to be built to avoid the risk of dollarisation.

The risks

As US dollar-denominated stablecoins account for 99% of the stablecoins market, the rise of their use in Africa indicates stablecoins have heightened dollarisation.

Dollarisation already exists and is widespread across Africa. It ranges from partial and informal to deep and systemic, depending on country conditions, but stablecoins accelerate and reinforce it. Traditional dollarisation (people and firms informally using US dollars for savings and trade) remains constrained by physical cash, bank access and foreign exchange controls.

Stablecoins make dollar-denominated liquidity instantly accessible on a mobile phone, bypassing banks, foreign exchange restrictions and domestic currency infrastructure. They become “digital dollars”, circulating outside the supervisory perimeter of central banks.

The US Genius Act brings issuers under US regulatory oversight. It guarantees that US dollar-denominated stablecoins will be safe, liquid and institutionally backed, making them more attractive than many African domestic currencies, especially in inflationary environments.

Consequently, what was once an informal hedge becomes a formal, globally credible digital alternative to local currency, accelerating capital flight, weakening deposit creation, and undermining domestic monetary policy.

This has direct monetary sovereignty implications for countries such as Nigeria and Kenya. In Nigeria, persistent foreign exchange shortages and naira volatility have pushed households and small enterprises into Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) as working capital and savings instruments.

Post-Genius Act, these instruments will become more institutionally robust, increasing dependence on US-dollar-based payment and settlement systems located and governed outside the country’s financial system and reducing the Central Bank of Nigeria’s ability to influence liquidity, lending and inflation.

In Kenya, where digital finance is already deeply embedded through M-Pesa, US dollar-stablecoins offer a hedge against the shilling, bypassing local credit creation and weakening the Central Bank of Kenya’s monetary transmission mechanism.

In both cases, the US Genius Act effectively shifts monetary authority away from African central banks and towards US regulators and private issuers – not by design, but through market incentives. Stablecoins thus do not merely mirror existing dollarisation; they legalise it at scale, embedding it into Africa’s digital financial systems.

There is also the risk of capital flight from African economies to the jurisdictions where the denominated stablecoins are backed.

In summary, stablecoins can truly advance financial inclusion in Africa, but heavy reliance on foreign-denominated stablecoins risks deepening dollarisation and weakening monetary sovereignty.

Next steps

To deal with these risks, African economies need stronger policy frameworks to build currency credibility and reduce the risk of dollarisation. This means that the fiscal deficit must be contained – meaning that governments must not spend far more than they earn. Current account balances must be managed, and foreign exchange, bank and corporate sector balances must be closely monitored.

My take on this issue is that central banks should be at the forefront of these developments, and this could also involve issuing their own central bank-issued tokenised money or digital currencies. This can co-exist alongside stablecoins rather than allowing privately issued, foreign-denominated stablecoins to become the dominant digital currency in circulation in a state.

So, while the dance at the stablecoin summit was commendable, I am concerned that only one dimension, looking at the benefits of stablecoins to facilitate payments and financial inclusion, is being put forward.

Policymakers must clearly articulate the implications of foreign-denominated stablecoins and prepare appropriate responses.

![]()

Iwa Salami does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Stablecoins are gaining ground as digital currency in Africa: how to avoid risks – https://theconversation.com/stablecoins-are-gaining-ground-as-digital-currency-in-africa-how-to-avoid-risks-271359