Source: The Conversation – USA – By Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino

Foreign policy is usually discussed as a matter of national interests – oil flows, borders, treaties, fleets. But there is a problem: “national interest” is an inherently ambiguous phrase. Although it is often presented as an expression of sheer force, its effectiveness ultimately rests on something softer – the manner in which a government performs moral authority and projects credibility to the world.

The style of that performance is part of the substance, not just its packaging. On Jan. 4, 2026, on ABC’s This Week, that style shifted abruptly for the U.S.

Anchor George Stephanopoulos pressed Secretary of State Marco Rubio to explain President Donald Trump’s declaration that “the United States is going to run Venezuela.” Under what authority, Stephanopoulos asked, could such a claim possibly stand?

Rubio dodged the question. He just said that the United States would enact “a quarantine on their oil.” Venezuela’s economy would remain frozen, unable “to move forward until the conditions that are in the national interest of the United States and the interests of the Venezuelan people are met.”

Rubio’s point presumed authority rather than pausing to justify it. It was a diplomacy of dominance – coercion dressed up as concern. The unspoken assumption was pure wishful thinking: that “national interest” would immediately prevail, flowing smoothly in all directions.

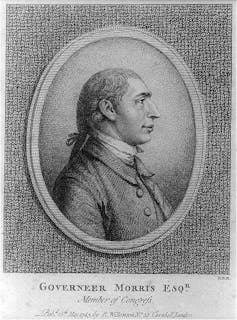

As a historian of the early republic and the author of a biography of George Washington, I’ve been reminded these days of how Washington – amid harsh storms unlike anything the country faces today – forged a vision that treated restraint, not self-justifying unilateralism, as the truest measure of American national interest.

Acknowledging burdens and consequences

In the 1790s, the United States faced a world ruled by corsairs and kings. The Atlantic was not yet an American lake. Spain blocked its western river, the Mississippi. Britain still held forts on U.S. soil. Revolutionary France tried to recruit American passions for European wars. And in North Africa, petty “Regencies,” as Europe politely called them, seized American ships at will.

The young nation was humiliated before it was strong. George Washington understood that humiliation intimately. Independence had freed America from Britain, but not from the world.

“Would to Heaven we had a navy,” he confessed to the Marquis de Lafayette in 1786, longing for ships “to reform those enemies to mankind, or crush them into nonexistence.” But such a fierce wish never became Washington’s foreign policy. Visibility invited peril; peril required composure.

In 1785, two American merchant vessels – the Maria of Boston and the Dauphin of Philadelphia – were captured by Algerian cruisers. Twenty-one sailors were chained, stripped and sold into slavery. Their families begged the government to pay ransom. Negotiators proposed paying tribute, a kind of protection-in-advance payment system. The price kept rising.

President Washington refused to be rushed by either pity or anger. Paying the extravagant sum, he warned his cabinet in 1789, “might establish a precedent which would always operate and be very burthensome if yielded to.”

Precedent mattered to Washington. A republic must measure not only what it can afford, but what it will be forced to feel tomorrow because of what it pays today.

The Trump administration’s approach to Venezuela demonstrates the opposite instinct. It represents a readiness to take unprecedented steps without pausing to acknowledge their burden and consequences.

Washington feared that habit of nearsightedness in foreign affairs precisely because he believed it corrupted empires – and could corrupt republics as well.

Neutrality as ‘emotional discipline’

The storms soon multiplied.

By 1793, Europe was already “pregnant with great events,” Washington wrote to Lafayette. The French Revolution, welcomed at first as a triumph of “The Rights of Man,” slid into terror and general war.

Citizen Genet, the French envoy to the United States, landed in Charleston, South Carolina, and proceeded to enlist American citizens’ help in France’s war with Britain by commissioning privateers in U.S. ports to prey on British ships. Genet did not request permission to do this from Washington.

Gratitude to France – indispensable ally during the Revolution, provider of fleets, soldiers and hard-to-forget loans – clashed with alarm at her new demands. A single misstep could have dragged the United States into another catastrophic conflict.

And yet, Washington responded to Genet not with rashness and bravado but with restraint made public law.

The 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality insisted that the “duty and interest of the United States” required “a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers.” Neutrality was an emotional discipline – the only source of authority.

Friendliness: strategy, not concession

President Washington knew that the road to successful pursuit of national interests was paved with international credibility.

Washington wanted America “to be little heard of in the great world of Politics,” preferring instead “to exchange Commodities & live in peace & amity with all the inhabitants of the earth.”

The first president pitched the republic’s voice toward ordinary people rather than rival powers. He spoke of “inhabitants,” not foreign enemies. He treated restraint – not self-justifying unilateralism – as the truest measure of national interest.

Library of Congress

Even when insulted or thwarted – by Spanish intrigues on the Florida frontier, by British seizures in the Caribbean, by pamphleteers accusing him of being a monarch in disguise – Washington’s tone remained measured.

On March 4, 1797, he would leave the presidency. His final creed was simple and devout: “My policy has been, and will continue … to be upon friendly terms with, but independent of, all the nations of the earth.”

For Washington, friendliness was a strategy, not a concession. The republic would treat other nations with civility precisely in order to remain independent of their appetites and quarrels.

Foreign policy as civic mirror

The statements from the Trump administration about Venezuela revive habits Washington once deplored: sovereignty managed through fear, pressure enforced by economic asphyxiation, domination smoothed over with promises of kindness. In this performance, U.S. interests function as a blank check, and restraint appears obsolete.

Yet foreign policy has never been only a ledger of advantage. It is also a civic mirror: the emotional register of a government that tells citizens what kind of nation is acting in their name, and whether it tries to balance national interest with responsibilities to others.

Washington believed America’s legitimacy abroad depended on patience and respect for the autonomy of others. The current approach to Caracas announces a different imagination: a power that boasts of quarantines, sets conditions – and calls the result partnership.

A republic must still defend its interests. But I believe it should also defend the temperament that made those interests compatible with independence in the first place. Washington’s America learned to stand among stronger powers without demanding to run them.

The question asked on “This Week,” then, is only the beginning.

The deeper question remains whether the United States will continue to perform power with the discipline of a constitutional republic – or surrender that discipline to the easy allure of what only seems to serve national interest, but fails to build credibility or relationships that endure.

![]()

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. George Washington’s foreign policy was built on respect for other nations and patient consideration of future burdens – https://theconversation.com/george-washingtons-foreign-policy-was-built-on-respect-for-other-nations-and-patient-consideration-of-future-burdens-272934