Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Gareth J. Fraser, Associate Professor of Evolutionary Developmental Biology, University of Florida

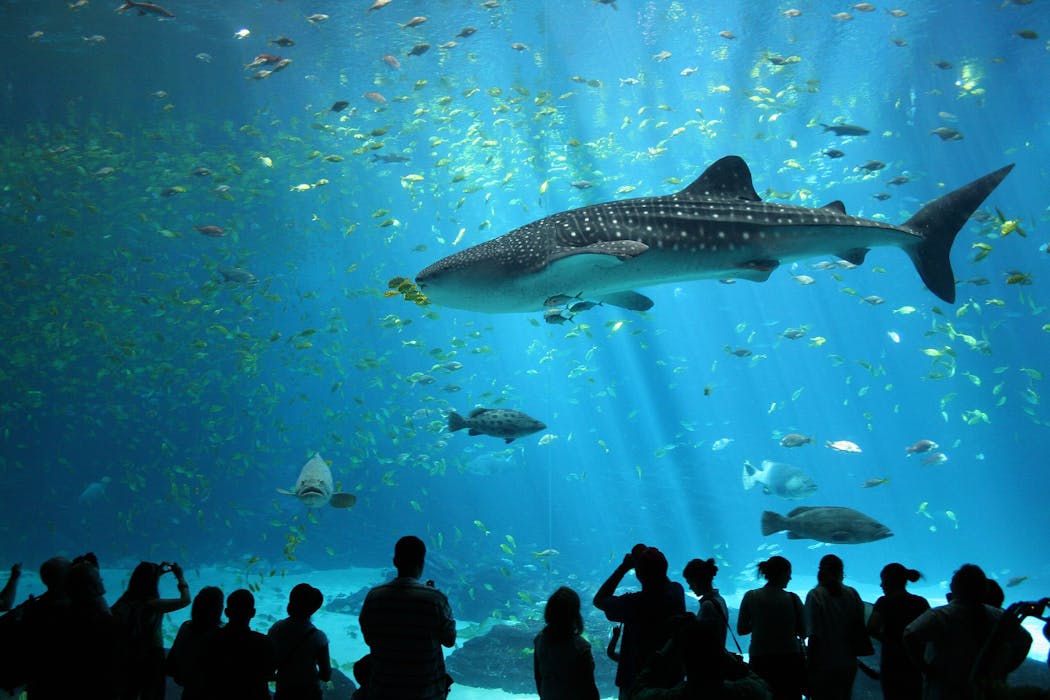

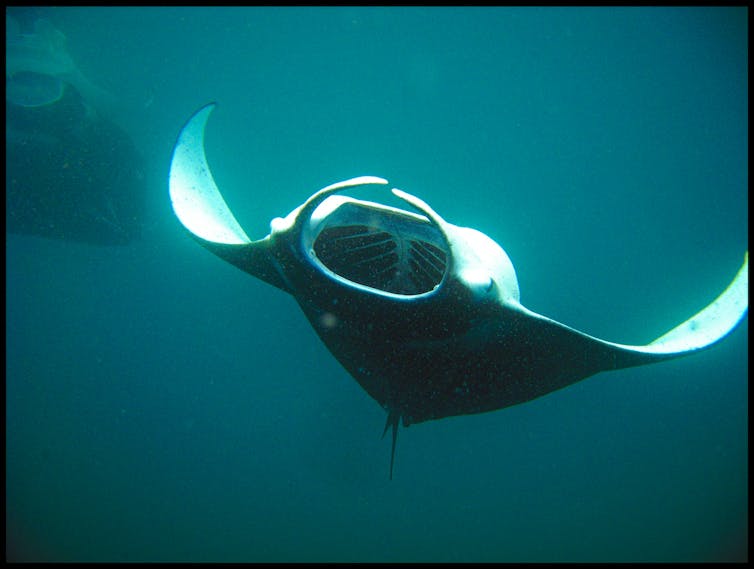

The world’s oceans are home to an exquisite variety of sharks and rays, from the largest fishes in the sea – the majestic whale shark and manta rays – to the luminescent but rarely seen deep-water lantern shark and guitarfishes.

The oceans were once teeming with these extraordinary and ancient species, which evolved close to half a billion years ago. However, the past half-century has posed one of the greatest tests yet to their survival. Overfishing, habitat loss and international trade have cut their numbers, putting many species on a path toward extinction within our lifetimes.

Scientists estimate that 100 million (yes, million) sharks and rays are killed each year for food, liver oil and other trade.

The volume of loss is devastatingly unsustainable. Overfishing has sent oceanic shark and ray populations plummeting by about 70% globally since the 1970s.

Jon Hanson/Flickr, CC BY-SA

That’s why countries around the world agreed in December 2025 to add more than 70 shark and ray species to an international wildlife trade treaty’s list for full or partial protection.

It’s an important move that, as a biologist who studies sharks and rays, I believe is long overdue.

Humans put shark species at risk of extinction

Sharks have had a rough ride since the 1970s, when overfishing, habitat loss and international trade in fins, oil and other body parts of these enigmatic sea dwellers began to affect their sensitive populations. The 1975 movie “Jaws” and its portrayal of a great white shark as a mindless killing machine didn’t help people’s perceptions.

One reason shark populations are so vulnerable to overfishing, and less capable of recovering, is the late timing of their sexual maturity and their low numbers of offspring. If sharks and rays don’t survive long enough, the species can’t reproduce enough new members to remain stable.

Losing these species is a global problem because they are vital for a healthy ocean, in large part because they help keep their prey in check.

Endangered and threatened species listings, such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List, can help draw attention to sharks and rays that are at risk. But because their populations span international borders, with migratory routes around the globe, sharks and rays need international protection, not just local efforts.

That’s why the international trade agreements set out by the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, are vital. The convention attempts to create global restrictions that prevent trade of protected species to give them a chance to survive.

New protections for sharks and rays

In early December 2025, the CITES Conference of the Parties, made up of representatives from 184 countries, voted to initiate or expand protection against trade for many species. The votes included adding more than 70 shark and ray species to the CITES lists for full or restricted protection.

The newly listed or upgraded species include some of the most charismatic shark and ray species.

The whale shark, one of only three filter-feeding sharks and the largest fish in the ocean, and the manta and devil rays have joined the list that offers the strictest restrictions on trade, called Appendix I. Whale sharks are at risk from overfishing as well as being struck by ships. Because they feed at the surface, chasing zooplankton blooms, these ocean giants can be hit by ships, especially now that these animals are considered a tourism must-see.

Gordon Flood/Flickr, CC BY

Whale sharks now join this most restrictive list with more well-known, cuddlier mammals such as the giant panda and the blue whale, and they will receive the same international trade protections.

The member countries of CITES agree to the terms of the treaty, so they are legally bound to implement its directives to suspend trade. For the tightest restrictions, under Appendix I, import and export permits are required and allowed only in exceptional circumstances. Appendix II species, which aren’t yet threatened but could become threatened without protections, require export permits. However, the treaty terms are essentially a framework for each member government to then implement legislation under national laws.

Another shark joining the Appendix I list is the oceanic whitetip shark, an elegant, long-finned ocean roamer that has been fished to near extinction. Populations of this once common oceanic shark are down 80% to 95% in the Pacific since the mid-1990s, mostly due to the increase in commercial fishing.

NOAA Fisheries

Previously the only sharks or rays listed on Appendix I were sawfish, a group of rays with a long, sawlike projection surrounded by daggerlike teeth. They were already listed as critically endangered by the IUCN’s Red List, which assesses the status of threatened and endangered species, but it was up to governments to propose protections through CITES.

Other sharks gaining partial protections for the first time include deep-sea gulper sharks, which have been prized for their liver oil used for cosmetics. Gulper shark populations have been decimated by unsustainable fishing practices. They will now be protected under Appendix II.

D Ross Robertson/Smithsonian via Wikimedia Commons

Appendix II listings, while not as strong as Appendix I, can help populations recover. Great white shark populations, for example, have recovered since the 1990s around the U.S. after being added to the Appendix II list in 2005, though other populations in the northwest Atlantic and South Pacific are still considered locally endangered.

Tope and smooth-hound sharks were also added to the Appendix II list in 2025 for protection from the trade of their meat and fins.

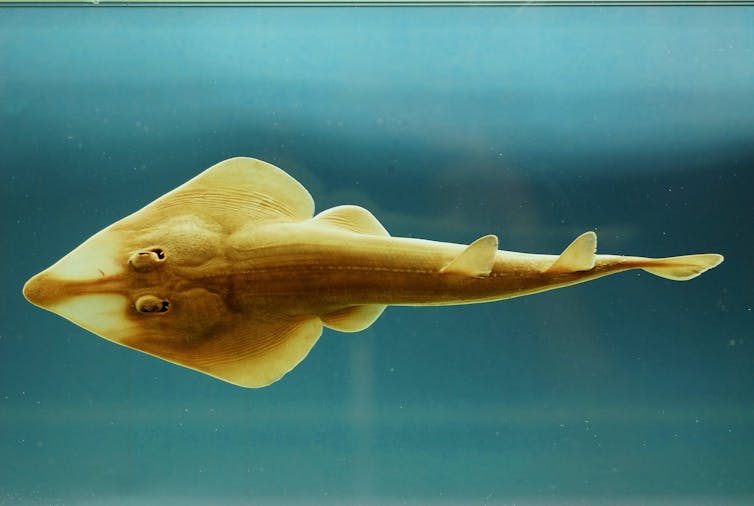

Several species of guitarfishes and wedgefishes, odd-shaped rays that look like they have a mix of shark and ray features and have been harmed by local and commercial fishing, finning and trade, were assigned a CITES “zero-quota” designation to temporarily curtail all trade in their species until their populations recover.

SEFSC Pascagoula Laboratory; Collection of Brandi Noble/Flickr, CC BY

These global protections raise awareness of species, prevent trade and overexploitation and can help prevent species from going extinct.

Drawing attention to rarely seen species

Globally, there are about 550 species of shark today and around 600 species of rays (or batoids), the flat-bodied shark relatives.

Many of these species suffer from their anonymity: Most people are unfamiliar with them, and efforts to protect these more obscure, less cuddly ocean inhabitants struggle to draw attention.

So, how do we convince people to care enough to help protect animals they do not know exist? And can we implement global protections when most shark-human interactions are geographically limited and often support livelihoods of local communities?

Increasing people’s awareness of ocean species at risk, including sharing knowledge about why their numbers are falling and the vital roles they play in their ecosystem, can help.

The new protections for sharks and rays under CITES also offer hope that more global regulations protecting these and other shark and rays species will follow.

![]()

Gareth J. Fraser is an Associate Professor at the University of Florida, and receives funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF).

– ref. Sharks and rays get a major win with new international trade limits for over 70 species – https://theconversation.com/sharks-and-rays-get-a-major-win-with-new-international-trade-limits-for-over-70-species-271386