Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Kerry E. Ratigan, Associate Professor of Political Science, Amherst College

China’s public response to the U.S. capture of Nicolás Maduro played out in a fairly predictable way, with condemnation of a “brazen” act of force against a sovereign nation and accusation of Washington acting like a “world judge.”

But behind closed doors, Beijing’s leaders are likely weighing the more nuanced implications of the raid: How will it affect China policy in Latin America? Can Beijing use the incident to burnish its image as an alternative global power? And what does the United States’ apparent disregard of international laws mean should China wish to make similar assertive moves in its own backyard?

As a scholar focusing on China’s global presence, I believe that these questions fit into a wider dilemma that President Xi Jinping faces in balancing two core Chinese tenets: the country’s long-standing commitment to noninterference in the domestic politics of other countries and its desire to strengthen strategic alliances and increase its presence in countries that, like Venezuela, provide it with crucial resources.

China’s LatAm ambitions

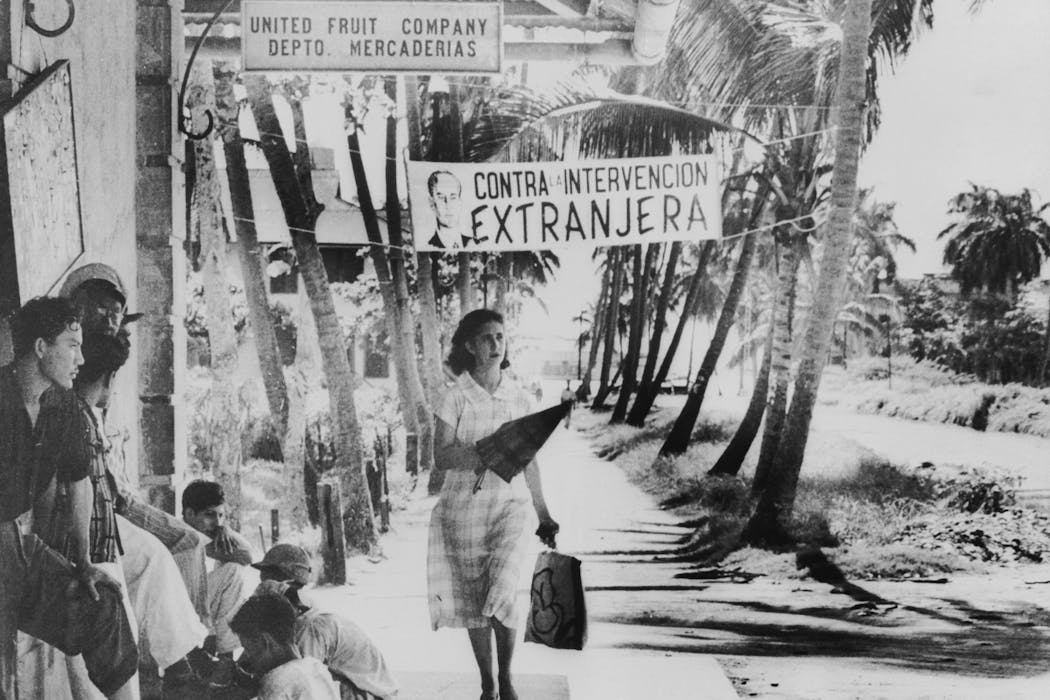

In recent years, China has become a more active and assertive player in international relations. And nowhere is this more true than in Latin America, where it has established deeper ties with countries like Venezuela.

China and Latin American countries have a mutually beneficial economic relationship. China needs natural resources, such as copper and lithium, that are abundant in Latin America, while China has been a ready source of infrastructure development.

For example, China has a strong presence in Peruvian mining, and the Chinese state-owned enterprise COSCO recently opened the high-tech Port of Chancay in Peru.

Hidalgo Calatayud Espinoza/picture alliance via Getty Images

And Chinese companies have been instrumental in upgrading public transportation to electric and hybrid systems across the region, such as the new metro line in Bogotá, Colombia.

China has become the second-largest trading partner across Latin America, behind the United States. For South America, it is the largest.

China’s relationship with Venezuela, as with other Latin American countries, took shape in the early 2000s. By 2013, China had lent Venezuela more energy finance than anywhere else in the world.

Even as mismanagement of Venezuela’s state-owned oil company and the country’s increasing slide into autocracy became apparent, China doubled down on lending. Throughout this process, China become the recipient of the vast majority of Venezuelan oil.

Accordingly, ties to the now-ousted Maduro remained strong to the end. Indeed, the last public act of Maduro before being snatched away from his bedroom by U.S. Delta Force commandos was reportedly a post on social media about his country’s strong bond with China.

But other than rhetoric and condemnations at the United Nations and elsewhere, Beijing can do little to directly counter the U.S. action.

Most likely, China will continue to condemn such policies, while quickly building up ties with Maduro’s successor and negotiating with Washington. China’s foreign ministry was at pains to stress commitment to Venezuela “no matter how the political situation may evolve,” following a Jan. 9 meeting between Beijing’s ambassador to Venezuela and Maduro’s successor, Delcy Rodriguez.

Jesus Vargas/Getty Images

More than anything, China will likely seek continued economic engagement with Venezuela. In 2024, Venezuela exported 642,000 barrels of oil per day to China — about three-quarters of the country’s production.

How the U.S. will now address Venezuelan oil — and by extension China’s ties to it — is not yet clear. President Donald Trump has pushed to redirect Venezuelan oil exports away from China and to the U.S, but he might not want to further escalate U.S.-China tensions.“

Broader than Venezuela

Even if Trump were to deprive China of Venezuelan oil, it is unlikely to change the trajectory of Beijing’s Latin America policy. After all, Venezuelan oil still only makes up 4% to 5% of China’s imported crude.

Indeed, China’s Latin America policy has not been discriminatory with regard to the political leanings of nations, even if Venezuela were to change course. China has well-established economic relations with almost every country in Latin America. For example, Argentina’s MAGA-aligned leader Javier Milei has courted China while in office and confirmed no intention to break ties now.

Nonetheless, Beijing is mindful of Trump’s reassertion of an aggressive Monroe Doctrine approach to the United States’ southern neighbors.

Unlike its own assertive military actions in its near waters, China has not meaningfully engaged in overt military or political influence in Latin America nations, in line with its noninterference stance.

And aside from China’s limited military support to allied nations through arms sales and joint-training exercises, some observers have been quick to note that China’s inaction following the U.S. attack on Venezuela exposes the hollowness of any security arrangement with Beijing.

Some may caution that Chinese projects like the Port of Chancay in Peru could be used for military purposes, or that Chinese control of utilities like electricity, as in Peru and Chile, presents a security threat to the host country and possibly to U.S. interests.

But for all of the Trump administration’s talk about how a country like China wants to intervene in Latin America, it is not Beijing that has suddenly renewed active military interventions in Latin America. And when push comes to shove, China likely has no wish to be involved militarily in Latin American affairs.

AFP via Getty Images

China as an alternative global power

If anything, U.S. intervention of the kind seen in Venezuela risks pushing Latin America further into China’s orbit.

The Maduro operation has been met with staunch criticism from countries including Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. It plays into a growing sense of disillusionment with the U.S.-dominated global order.

And here, China might see an opportunity.

In recent decades, China has gone from a being a “rule taker” to a “rule maker” in international politics, meaning that Beijing increasingly sees geopolitics as the U.S once did: something ripe for remaking in its own image.

In addition to assuming leadership roles in major U.N. agencies, China under Xi has increasingly positioned itself as a leader of the Global South. It has developed international organizations that seem to offer an alternative to the institutions tied to the existing U.S.-led global order.

For example, Beijing created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as an alternative lender to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. China also offers development finance through the New Development Bank and its two “policy banks” — the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China.

In international governance, China has emphasized multilateralism and dialogue as the basis for new global initiatives, pledging adherence to the principles of the U.N. charter and respecting sovereignty.

Skeptics may claim this as window dressing for strategic global ambitions. But if the intention is for China to remold international governance under its guidance, then the actions of the current U.S. administration pave the way for Beijing to promote its vision.

Under Trump, the U.S. has undermined global governance bodies, pulling out of a series of bodies and commitments, including the Paris climate accord, the World Health Organization and the U.N. Human Rights Council.

The Chinese government’s condemnations of the U.S. actions in Venezuela have highlighted the impact it had on certain international norms, notably law. But it has left it to sympathetic voices outside government to make the logical next jump.

Writing for the state-run China Global Television Network, Renmin University Professor Wang Yiwei argued that the international system suffers from American imperialism and that the “only nation capable of dismantling these three pillars [of imperialism, colonialism and hegemony] is undoubtedly China.” The article was published in Chinese and English on CGTN — a clear nod that it is intended for both a domestic and international audience.

Carving up the world?

While China has been quick to condemn the U.S. intervention in Venezuela, some observers have speculated that it could provide China a blueprint for potential action in Taiwan.

Regardless of China’s intentions toward Taiwan, Washington’s apparent pushing of a “spheres of influence” doctrine won’t automatically find unfavorable ears in Beijing.

At some level, China may actually accept U.S. dominance in Latin America — even as it protests such action — should this advance a longtime goal for Beijing in having its own “Monroe Doctrine” in its near waters.

![]()

Kerry E. Ratigan receives funding from the Wilson Center and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange.

– ref. How is China viewing US actions in Venezuela – an affront, an opportunity or a blueprint? – https://theconversation.com/how-is-china-viewing-us-actions-in-venezuela-an-affront-an-opportunity-or-a-blueprint-273076