Source: The Conversation – UK – By Anastasia Topalidou, Research Fellow (Perinatal Biomechanics and Health Technologies), University of Lancashire

Maternal and newborn deaths are rising globally, not just in low- and middle-income countries, but in wealthy nations too. Researchers have described the situation as a “global failure” and a “major scandal”.

In the UK, more women are now dying during pregnancy and childbirth than at any time in the past 20 years, despite a fall in the birth rate. A national maternity investigation has just been launched, and public concern is growing.

Yet while politicians and healthcare leaders debate staffing levels and service delivery, one major contributor to poor outcomes is being almost entirely overlooked: biomechanical complications during labour.

Biomechanics refers to how the body moves and responds to physical forces. During pregnancy, it describes how the body adapts to the increasing demands of carrying a growing baby. During labour, it involves some of the most physically intense and complex actions the human body can perform, as it prepares for and facilitates the delivery of a baby.

After analysing 87 studies from around the world, we discovered that not a single one had ever investigated the biomechanics of labour. None examined how women’s bodies actually move, adapt or respond during birth. All the research focused solely on pregnancy. And despite rising maternal deaths in the UK, not a single antenatal biomechanics study had been conducted here either.

This isn’t just an academic oversight. Labour is biomechanically intense, involving force, posture, motion, muscle control and joint loading. Without evidence on how positions, manoeuvres or techniques affect the birthing body, maternity care relies largely on tradition, anecdotal evidence and outdated assumptions.

A dangerous lack of diversity

Some pregnancy-related biomechanical changes have been documented, but these vary widely from person to person. There is no “typical” pathway. Yet standard guidance assumes a one-size-fits-all model, often failing to account for these variations.

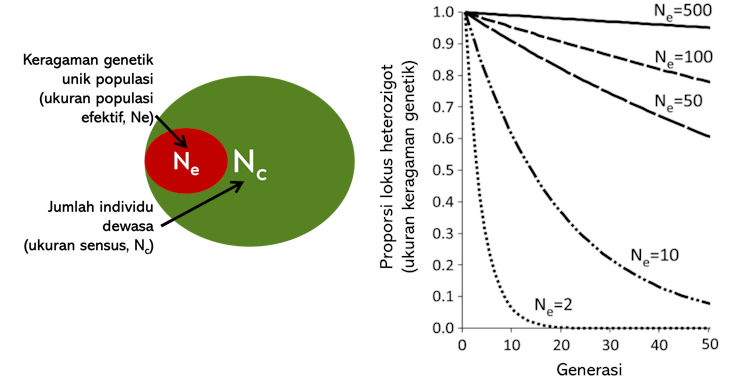

Worse still, almost no studies included data on ethnicity. Only one mentioned participants’ ethnic background, but it did not analyse the data by group or explore any differences. That is a serious gap, given that anatomical features like pelvic shape, joint mobility, spinal alignment and culturally shaped movement patterns can vary across populations. These differences could significantly affect how women move and give birth, yet they remain completely overlooked.

This is a serious problem, especially in the UK. Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) – the national programme that investigates maternal and infant deaths – along with other official reports, consistently show that Black and Asian women are nearly three times more likely to die during childbirth than white women. If all the biomechanical knowledge we have is based on white bodies, yet clinical guidance is applied universally, we may be missing important risks or needs. This lack of inclusive data could be contributing to the persistent racial disparities in maternal outcomes.

We also found that even widely used techniques such as squatting or the McRoberts’ manoeuvre – a common emergency intervention – have never been biomechanically validated during labour. This means that no one has scientifically tested how these movements affect the body’s joints, muscles, and bones during actual childbirth. So, we don’t know if they help, hinder, or have no measurable impact on the birthing process.

A handful of studies tested some of these positions on pregnant women in static, controlled conditions, but none included women in active labour. Those studies revealed no measurable advantage for any of the positions tested. Even the McRoberts’ manoeuvre did not significantly change pelvic or spinal alignment.

That means decades of advice, clinical practice, and emergency response protocols may be based on theory and biomechanical guesswork, rather than evidence. And while these techniques are used every day – often in urgent situations – they have never been scientifically tested on women in active labour. So no clinical studies have examined how these interventions actually affect the birthing body in real time. We don’t know if they work as intended, or if they could be refined to improve safety.

Tradition over science

The consequences of this blind spot are not theoretical or a matter of academic curiosity. They’re about safety, dignity and fairness. Maternal and neonatal outcomes are getting worse. Stillbirths and deaths shortly after birth have increased. Behind these statistics are real families and real tragedies. Many of which may have been preventable.

So why haven’t we filled this gap? Part of the reason is technical: traditional biomechanical systems are difficult to use in clinical settings. But that’s no excuse. New technologies are being developed all the time. If we have the capability to launch rockets and explore space, we should surely be able – and arguably obliged – to understand the basic biomechanics of human birth.

The real barrier is structural neglect. Women were routinely excluded from clinical research until the 1990s, and even now, research into women’s health remains massively underfunded and overlooked. As a result, childbirth, one of the most common yet life-altering events in medicine, is still shaped by untested ideas.

This isn’t just a research gap. It’s a failure of safety, equity and scientific responsibility. We are delivering babies in the dark, and those most at risk are often the ones who are left behind.

![]()

Dr Topalidou received a Pre-Application Support Fund Award from the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (NIHR ARC NWC) to support this work. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

– ref. Why we still don’t understand what happens to women’s bodies during labour – https://theconversation.com/why-we-still-dont-understand-what-happens-to-womens-bodies-during-labour-261803