Source: The Conversation – UK – By Shweta Singh, Assistant Professor, Information Systems and Management, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

Generative AI promises to help solve everything from climate change to poverty. But behind every chatbot response lies a deep environmental cost.

Current AI technology requires the use of large datacentres stationed around the world, which altogether draw enormous amounts of power and consume millions of litres of water to stay cool. By 2030, datacentres are expect to consume as much electricity as all of Japan, according to the International Energy Agency, and AI could be responsible for 3.5% of global electricity use, according to one consultancy report.

The continuous massive expansion of AI use and its rapidly growing energy demand would make it much harder for the world to cut its carbon emissions by switching fossil fuel energy sources to renewable electricity.

So, we are left with pressing questions. Can we harness the benefits of AI without accelerating environmental collapse? Can AI be made truly sustainable – and if so, how?

We are at a critical juncture. The environmental cost of AI is accelerating and largely unreported by the firms involved. What the world does next could determine whether AI innovation aligns with our climate goals or undermines them.

At one end of the policy spectrum is the path of complacency. In this scenario, tech companies continue unchecked, expanding datacentres and powering them with private nuclear microreactors, dedicated energy grids or even reviving mothballed coal plants.

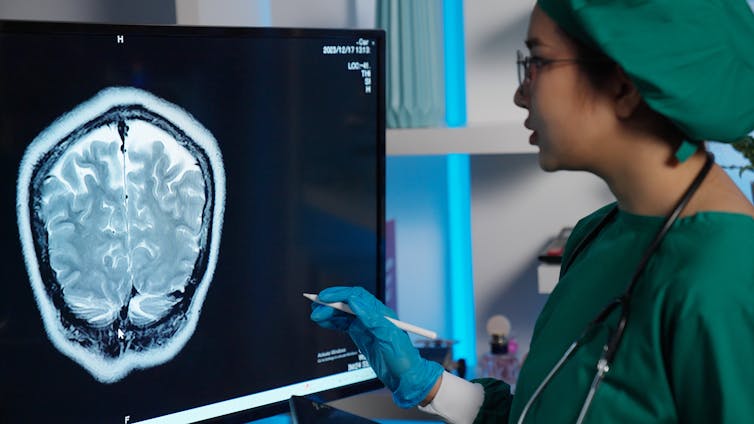

Dobresum / shutterstock

Some of this infrastructure may instead run on renewables, but there’s no binding requirement that AI must avoid using fossil fuels. Even if more renewables are installed to power AI, they may compete with efforts to decarbonise other energy uses. Developers may tout efficiency gains, but these are quickly swallowed by the rebound effect: the more efficient AI becomes, the more it is used.

At the other end lies a more radical possibility: a global moratorium or outright restriction on the most harmful forms of AI, akin to international bans on landmines or ozone-depleting substances.

This is politically improbable, of course. Nations are racing to dominate the AI arms race, not to pause it. A global consensus on bans is, at least for now, a mirage.

But in between complacency and prohibition lies a window – rapidly closing – for decisive, targeted action.

This could take many different forms:

1. Mandatory environmental disclosure:

AI companies could report how much energy, water and emissions are used to train and use their models. Having a benchmark helps to measure progress while improving transparency and accountability. While some countries have started to impose greater corporate sustainability reporting requirements, there is significant variation. While mandatory disclosures alone won’t reduce consumption directly, they are an essential starting point.

2. Emissions labelling for AI services:

Just as carbon emissions labels on restaurant menus or supermarket produce can guide people to lower-impact options, users could be given a chance to know the footprint of their digital choices and AI providers, like efforts to measure the carbon footprint of websites. In the US, the blue Energy Star label, one of the country’s most recognisable environmental certifications, helps customers choose energy-efficient products.

Alternatively, AI providers could also temporarily reduce functionality to account for varying levels of renewable energy available that powers them.

3. Usage-based pricing tied to impact:

Existing carbon pricing aims to ensure that heavy users should pay their environmental share. Research shows that this works best when carbon is priced across the economy for all companies, rather than just specifically targeted at individual sectors. Yet much depends on digital tech providers fully accounting for such environmental burdens in the first place.

4. Sustainability caps or “compute budgets”:

This would especially target non-essential or commercial entertainment applications. Organisations may limit their employees’ usage similar to how they restrict heavy office printing or indeed corporate travel. As companies begin to measure and manage their indirect supply chain emissions, energy and water footprints from using AI may require new business policies.

5. Water stewardship requirements in water-stressed regions:

A simple regulation here would be to ensure no AI infrastructure depletes local aquifers unchecked.

Market forces alone will not solve this. Sustainability won’t emerge from goodwill or clever efficiency tricks. We need enforceable rules.

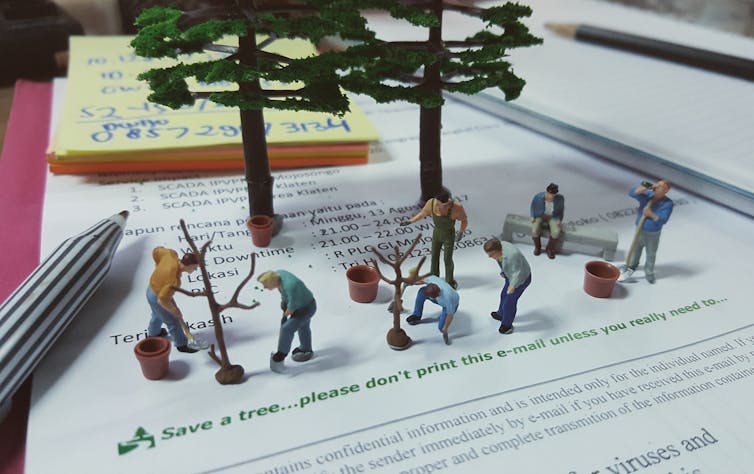

Consumer awareness isn’t enough

Awareness does help. But expecting individuals to self-regulate in a system designed for ease-of-use is naive. “Only use AI when needed” might soon be like “Don’t print this email” a decade or two ago – well-meaning, often ignored and utterly insufficient.

awstoys / shutterstock

The world is building an AI-powered future that consumes like an industrial past. Without guardrails, we risk creating a convenience technology that accelerates environmental collapse.

Maybe AI will one day solve the problems we couldn’t, and our concerns about emissions or water will seem trivial. Or maybe we just won’t be around to worry about them.

The way we engage with AI now – blindly, cautiously, or critically – will shape whether it serves a sustainable future, or undermines it. Policymakers should treat AI as it would any other wildly profitable resource-intensive industry, with carefully thought through regulation.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Frederik Dahlmann receives funding from National Institute for Health & Care Research (NIHR).

Shweta Singh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Regulating AI use could stop its runaway energy expansion – https://theconversation.com/regulating-ai-use-could-stop-its-runaway-energy-expansion-258425