Source: The Conversation – UK – By Putu Agus Khorisantono, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet

Taste is often thought to be controlled solely by our tastebuds. But maybe you’ve noticed how food can taste bland when you have a cold and and your nose is blocked? This common experience highlights just how important our sense of smell is when it comes to taste – and how strongly the two are connected.

When we eat something, two processes happen simultaneously. First, the taste buds on the tongue are activated by the food. At the same time, the odours from these foods travel up through the mouth and into the back of the nose – a process called “retronasal smelling”. These two processes combine in the brain to create the sensory experience we call flavour.

The connection between these two processes is extremely powerful. Just as blocking your sense of smell can alter the way your food tastes, aroma alone can also be perceived as a taste.

But though this phenomenon is well established, the mechanism behind it remained unknown. So we conducted a study that set out to understand why smell can control our taste. We discovered that aroma triggers a similar response in the brain as taste does – even if a person hasn’t actually “tasted” anything.

To conduct our study, we recruited 25 people to our laboratory. For the first part of the study, each person was given a variety of different beverages to test. These tasted and smelled of different sweet and savoury flavours. For the sweet flavours, participants were given beverages that tasted and smelled like golden syrup, raspberry or lychee. For the savoury flavours, the beverages tasted and smelled of bacon, chicken broth or onion.

Our tasters then performed a learning task where they had to correctly remember the abstract visual cues each flavour had been assigned. This helped the participants to establish a strong connection between the taste and smell components of each flavour.

Next, we scanned each person’s brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This allowed us to see the brain’s responses to the various stimuli by measuring changes in blood flow. During these scanning sessions, we presented our volunteers with drinks that had only one type of sensory input – either taste or smell, but not both.

Then we used machine learning to identify unique patterns in how different areas of the brain responded when it was exposed to a sweet or savoury taste, or a sweet or savoury aroma.

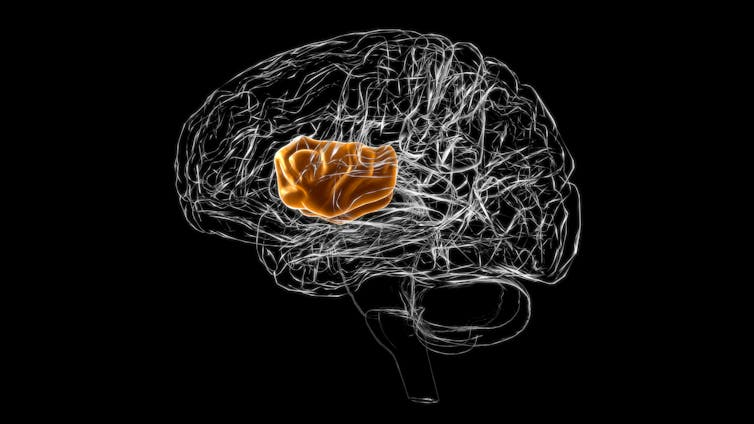

As expected, we saw that the insula (the brain area that is the primary taste hub) showed different responses to sweet and savoury tastes. But it also showed a pattern of response to both sweet and savoury odours.

mybox/ Shutterstock

Most importantly, the odour response patterns overlapped with the taste patterns. This means that the insula responds to odours in a similar way as it responds to taste. So if a person smells something sweet, the brain would respond in the same way as if you’d actually eaten something sweet.

This overlap was even more pronounced when we looked specifically at the insula’s “dysgranular” and “agranular” regions. These regions are involved in processing perceptual signals from within the body. Since hunger and thirst signals also come from the body, this could suggest that the brain uses the odour of a food to determine whether it would satisfy the body’s nutritional needs.

Flavour response

This changes what we think about the insula’s role in food perception. It was once thought to just be a taste processing site, but our research shows it’s a far more sophisticated structure that takes in taste information and integrates it with other sensory components to create flavour.

These results were also the first ever to directly show the overlapping brain response between tastes and smells in the brain’s taste centre. Essentially, this indicates that when we eat something, we perceive food odours as tastes because they induce the same response patterns in the insula as actual tastes.

Our findings have exciting implications for understanding sensory experiences and could lead to advances in the field.

The clearest application is creating innovative foods and drinks that use aromas to compensate for the removal of less healthy ingredients – such as sugar, salt or fat. But there’s still a lot we need to learn about how odours and tastes affect our dietary habits.

Understanding how this mechanism works could also help people with a reduced sense of smell (anosmia) since they may form flavour preferences differently than the rest of the population.

We’re currently conducting a follow-up study to see if this phenomenon also occurs with odours that are perceived outside of the mouth (known as orthonasal smelling). This happens when we sense an odour by sniffing it. Orthonasal smelling plays a pivotal role in food anticipation. If this does lead to a similar activation as taste, it would mean that smell is crucial to hunger regulation.

In fact, rodent research indicates that food smells encourage eating by activating a subgroup of neurons. And, this activation is inhibited when that food is eaten. Understanding how this works would unlock a host of techniques to manage eating behaviour.

Our study also showed that while responses to tastes and odours overlap, this flavour response changed throughout the course of the experiment – becoming less distinct as time went on. This suggests that when you’re repeatedly exposed to a smell without tasting it, the brain stops associating the two over time. So you might stop “tasting” these aromas if you don’t reinforce the connection occasionally.

Better understanding just how the brain processes our sense of taste and smell could have important implications for influencing eating behaviour. Some day, it could be possible to reduce cravings and guide food choices using smell alone.

![]()

Janina Seubert receives funding from the European Research

Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and

innovation programme (grant agreement n° 947886) and from the

Swedish Research Council (VR 2018-0318 and VR 2022-02239).

Putu Agus Khorisantono does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Smell triggers the same brain response as taste does – even if you haven’t eaten anything – https://theconversation.com/smell-triggers-the-same-brain-response-as-taste-does-even-if-you-havent-eaten-anything-264922