Source: The Conversation – USA – By Garret Martin, Hurst Senior Professorial Lecturer, Co-Director Transatlantic Policy Center, American University School of International Service

When it comes to shutdowns, the U.S. is very much an exception rather than the rule.

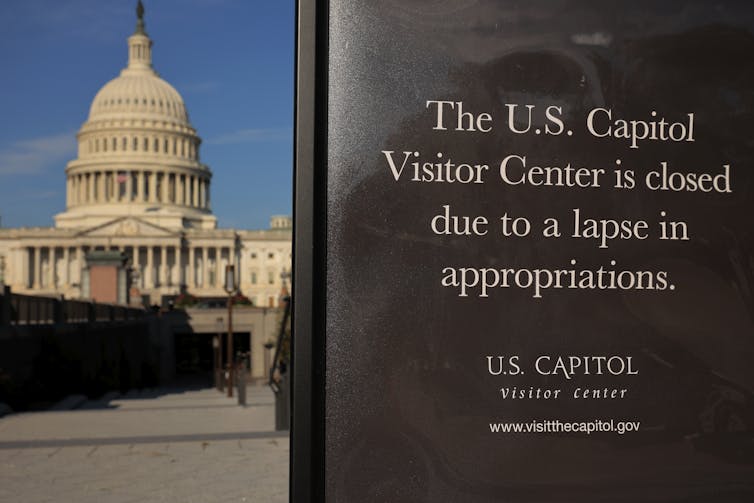

On Oct. 1, 2025, hundreds of thousands of federal employees were furloughed as the business of government ground to a halt. With negotiations in Congress seemingly deadlocked over a funding deal, many political watchers are predicting a lengthy period of government closure.

According to the nonpartisan nonprofit Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the latest shutdown represents the 20th such funding gap since 1976.

But it doesn’t have to be like this – and in most countries, it isn’t. Other Western democracies experience polarization and political turmoil, too, yet do not experience this problem. Take for example the U.K., traditionally one of Washington’s closest allies and home to the “mother of parliaments.”

In the British system, government shutdowns just don’t happen – in fact, there has never been one and likely never will be.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

So why do they occur in Washington but not London? Essentially, it comes down to four factors: the relative power of the legislature; how easy it is to pass a budget; the political stakes at play; and distinctive appropriation rules.

1. Legislative power

There are significant differences in how the legislatures of the U.K. and U.S. shape the budgetary process.

In the U.K., only the executive branch – the party or coalition in power – has the authority to propose spending plans. Parliament, which consists of members from all political parties, maintains an oversight and approval role, but it has very limited power over the budgetary timeline or to amend spending plans. This is a stark contrast with the U.S., where Congress – which may be split or controlled by a party different to the executive – plays a far more consequential role.

The U.S. president starts the budget process by laying out the administration’s funding priorities. Yet, the Constitution grants Congress the power of the purse – that is, the power to tax and spend.

Moreover, past legislation has bolstered congressional control. The 1974 Congressional Budget Act helped curtail presidential involvement in the budgeting process, giving Congress more authority over the timeline. That gave Congress more power but also offered it more opportunities to bicker and derail the budgetary process.

2. Thresholds to pass a budget

Congress and the U.K. Parliament also differ when it comes to their voting rules. Passing the U.S. budget is inherently more complicated, as it requires the support of both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

In Parliament, however, the two houses – the elected House of Commons and unelected House of Lords – are not equally involved. The two Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 limited the power of the House of Lords, preventing it from amending or blocking laws relating to budgeting.

Additionally, approving the budget in Westminster requires only an absolute majority of votes in the House of Commons. That tends to be quite a straightforward hurdle to overcome in the U.K. The party in power will typically also command a majority of votes in the chamber or be able to muster one up with the support of smaller parties. It is not, however, so easy in Congress. While a simple majority suffices in the House of Representatives, the Senate still has a 60-vote requirement to close debates before proceeding with a majority vote to pass a bill.

3. Political stakes

U.S. and U.K. politicians do not face the same high stakes over budget approval. Members of Congress may eventually pay a political price for how they vote on the budget, but there is no immediate threat to their jobs. That is not so in the U.K.

Indeed, the party or coalition in power in the U.K. must maintain the “confidence” of the House of Commons to stay in office. In other words, they need to command the support of the majority for key votes. U.K. governments can actually fall – be forced to resign or call for new elections – if they lose formal votes of confidence. Since confidence is also implied in other major votes, such as over the annual budget proposals, this raises the stakes for members of Parliament. They have tended to think twice before voting against a budget, for fear of triggering a dissolution of Parliament and new elections.

4. Distinctive appropriation rules

Finally, rules about appropriation also set the U.S. apart. For many decades, federal agencies could still operate despite funding bills not being passed. That, however, changed with a ruling by then-Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti in 1980. He determined that it would be illegal for governments to spend money without congressional approval.

That decision has had the effect of making shutdowns more severe. But it is not a problem that the U.K. experiences because of its distinct rules on appropriation. So-called “votes on account” allow the U.K. government “to obtain an advance on the money they need for the next financial year.”

This is an updated version of an article that was first published by The Conversation U.S. on Sept. 28, 2023.

![]()

Garret Martin receives funding from the European Union for the Transatlantic Policy Center, which he co-directs.

– ref. Shutdowns are as American as apple pie − in the UK and elsewhere, they just aren’t baked into the process – https://theconversation.com/shutdowns-are-as-american-as-apple-pie-in-the-uk-and-elsewhere-they-just-arent-baked-into-the-process-266553