Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Leda Stawnychko, Associate Professor of Strategy and Organizational Theory, Mount Royal University

In an era of heightened political polarization, merely longing for civility is no longer enough. Understanding just how to debate and respectfully disagree has become truly imperative, now more than ever and for a couple good reasons.

Humans are wired for connection. Our brains evolved for collaboration.

Sharing experiences with people who see the world as we do feels affirming. It makes collaboration possible. And in prehistoric times, our survival depended on it. Working together meant protection, food and belonging, while conflict risked exclusion or, worse, death.

But civility isn’t about avoiding conflict, it’s about choosing to see the other’s humanity all while fully disagreeing with them.

The weaponization of civility

Avoiding conflict for the sake of civility comes at a cost.

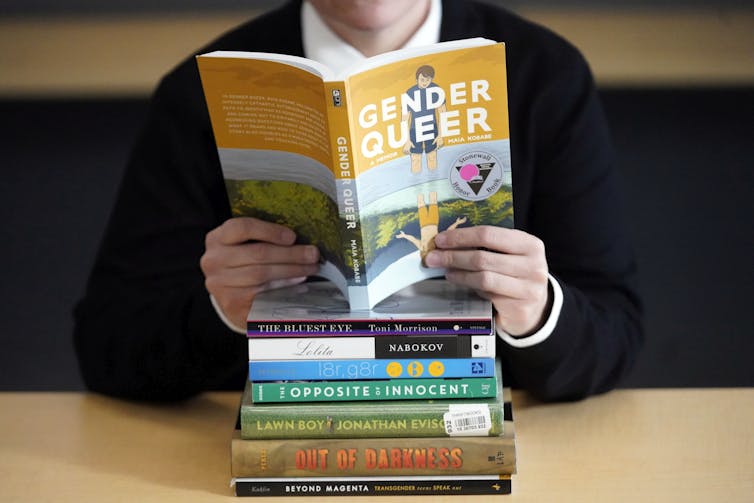

Societies move forward when people are willing to engage in honest disagreement, exposing blind spots and opening paths to progress. Yet too often, calls for civility are used as tools of oppression, privileging those already served by the status quo.

History is full of examples — from women’s suffrage to the civil rights movement — where demands for “politeness” were used to quiet those pushing for change.

When discomfort is mistaken for disrespect, dissidence is curtailed and legitimate anger invalidated. At such moments, civility ceases to be a virtue and becomes a mechanism of control.

This helps explain why reactions to “cancel culture” have been so strong — a response to the ways in which demands for consideration can be seen as silencing rather than inviting dialogue. Recent events from cancelled university lectures to the suspension of high-profile comedic television hosts reveal how fear of controversy increasingly constrains open expression.

Maintaining civility is a delicate balance. When disagreement turns uncivil, especially in the public sphere, people tend to withdraw altogether, eroding the very dialogue that civility is meant to protect.

Grounding civility in dignity

True civility begins with a disposition of the heart — a sincere recognition of the dignity of others.

From that foundation flow the actions and skills that make respectful engagement possible: listening with curiosity, showing courtesy and extending respect even in disagreement.

Civility, however, is not simply about being polite; it is about choosing to see others as moral equals, worthy of being heard and understood. In fact, civil disagreement is healthy and necessary.

In workplaces, teams that can debate ideas respectfully tend to be more innovative and make better decisions than those that avoid conflict altogether.

When grounded in dignity rather than deference, civility enables the kind of disagreement that strengthens communities rather than divides them. It reflects the diversity of our experiences, interests and values — fuelling the dialogue, learning and innovation that help societies grow stronger.

Some conversations feel unsafe

Certainly, some engagements feel riskier than others. Part of this comes down to our physiological makeup — factors largely beyond our control.

The balance of hormones and neurotransmitters in our bodies influences whether we are more prone to react impulsively or respond calmly in moments of tension. This biological wiring is continually shaped by our experiences, including how we’ve learned to navigate conflict and connection in the past.

When our bodies and minds are already operating near their stress limits — for example, while caring for a sick child, navigating a divorce or managing financial strain — our capacity to engage thoughtfully shrinks. In those moments, even minor disagreements can feel overwhelming, not because of the issue itself but because our systems are already overtaxed.

These personal limits are magnified by the social environments we inhabit. Social media, for instance, amplifies echo chambers and rewards outrage, reinforcing our tendency to interact only with those who share our views.

In such spaces, argument often becomes interest-driven rather than truth-oriented — more about winning than understanding.

When one or both sides see their position as morally correct, any deviation from it is framed as wrong, leading to emotionally charged, difficult-to-resolve conflicts. As soon as our moral convictions harden into absolutes, compromise becomes nearly impossible.

And without shared moral ground, we begin to justify the dehumanization of the “other,” treating those who disagree not as mistaken, but as immoral — and therefore unworthy of empathy.

How to have tough conversations

Productive disagreement begins with self-awareness.

Start by asking why a certain conversation feels risky. What emotions or experiences might be shaping your reaction? Then pause to decide whether this discussion is worth having, and with whom.

What are your motives for engaging? Are you entering a genuine exchange or simply entertaining debate for debate’s sake? Does this context or person matter to your learning, your work or your advocacy? Or are you engaging in discourse that reinforces division rather than insight?

Communication skills also matter because when we believe in our ability to communicate effectively and influence another person’s perspective, we feel safer and more confident entering a difficult conversation. People who see a disagreement as manageable — and themselves as capable of managing it — are more likely to engage constructively rather than withdraw in frustration or defensiveness.

Cultivating skills in listening, reflection and self-regulation, together with dispositions such as open-mindedness, tact, empathy and courage, creates the conditions for genuine and respectful dialogue — the kind that not only builds understanding but sustains relationships and strengthens communities over time.

Ultimately, civility is about engaging in debates with ethics, humility and humanity.

It asks us to create space for honest conversations — where discomfort signals growth, not danger, and where disagreement strengthens rather than fractures our society.

![]()

Leda Stawnychko has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the Business Schools Association of Canada (BSAC).

Maryam Ashraf does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Agree to disagree: Why we fear conflict and what to do about it – https://theconversation.com/agree-to-disagree-why-we-fear-conflict-and-what-to-do-about-it-267576