Source: Radio New Zealand

Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s first ever digital minister, told those attending the Munich Cyber Security Conference that Taiwan is using AI to fight disinformation. Photo: JP YIM

For Taiwan, the threat of Chinese military invasion is less pressing than an invasion many see as ongoing – an onslaught of disinformation.

As the world grapples with ways to tackle waves of disinformation and fake news, one country is taking the battle to every level of society, from temples and community halls to a dedicated government ministry.

In Taiwan where there are fears that the growing online onslaught could undermine the treasured democratic system, Taiwanese citizens are taking matters into their own hands.

“Taiwan has gone through so much change,” Mark Hanson said, a Taiwan-based New Zealand journalist.

“From a country that was under martial law right into the late 1980s, Taiwan has developed into a thriving economy, a leader and innovator in technology, an open democratic society, the first place in Asia with gay marriage.

“There have just been so many improvements made here and it’s scary that all of that could be washed away.

“The information war has already started, a long time ago,” Hanson’s friend Nelly said, who is an English teacher in Taichung.

“There’s some invisible threats everywhere, like the cyber attacks and [fake] news. It happens to us everywhere.”

In the final of three reports from Taiwan, The Detail looks at the claims that mainland China uses influencers, television stars, offshore “content farms” and generative artificial intelligence to swamp the island state with disinformation, and talks to two young people about their groundbreaking projects that others want to copy.

As China pursues sovereignty claims over Taiwan under the One China Principle, the online war is seen by many Taiwanese as a much greater threat than China’s military build up and trade sanctions.

‘They don’t hide any more’

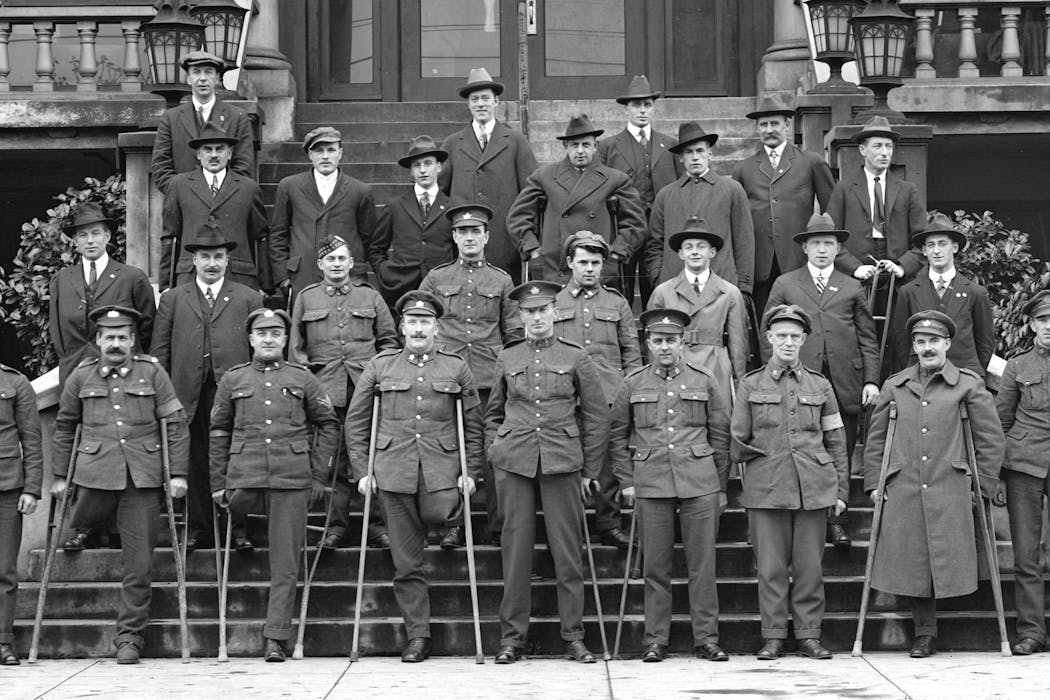

Investigative journalist and podcaster Jason Liu is now dedicated to tackling disinformation at community level.

Jason Liu is an investigative journalist. Photo: Sharon Brettkelly

He’s spent five years across eight countries, including Ukraine, looking at how disinformation affects societies and has written about the so-called “content mill empire behind online disinformation”.

He said the Chinese propaganda messages were easy to spot and blatant, and sometimes came from within Taiwan.

“You have different ways to identify if they are pro-China or coordinated with pro-China actors. If they are repeating the propaganda from state-sponsored media from mainland China then they are part of the coordinated behaviour.

“Secondly, they don’t hide any more right now, they share the same picture, they use the state press release or they are making money out of this news cycle.”

Liu said people in the “online army” or public relations companies making money from Chinese state-sponsored propaganda have told him that AI had made it easy.

“Everyone can do it, everyone can repost hundreds of messages every day. If you want to earn some money from the Chinese government you just have to have the contacts to understand who would be willing to pay for it.

“It’s now easy to buy the applications to buy bots, to buy accounts to spread information.”

Liu said he had interviewed people in Mandarin-speaking countries like Malaysia and Singapore who made money from pushing disinformation into Taiwan.

His solution was simple, a programme that went into temples, schools and community halls, getting people offline and meeting face-to-face, where he talked about his international work, showed documentaries and talked about his articles.

“We are hosting more and more in-person events with children with students.

Billion Lee and Johnson Liang, co-founders of CoFact fact-checking collaboration Photo: Sharon Brettkelly

“That’s what people in my generation, the activists, media literacy petitioners, we are trying to bring people offline to meet each other. Then you don’t only read [about] Taiwan from the bots, from the fake accounts, from the social media.”

‘I believe in freedom, democracy’

Billion Lee took a different approach with a programme that had gained international attention.

She is the co-founder of CoFact, an NGO that built a chatbot to fact-check and fight disinformation, where the editorial team works with volunteers in verifying news or content.

The Detail met her off the plane from Portugal where she had attended a conference on fake information, before she headed to a hackathon weekend where like-minded engineers, designers and tech experts shared new ways of recognising and tackling disinformation.

The CoFact website also runs tutorials in several languages, explaining how users can filter news topics and sift out fake stories.

“What CoFact tries to do is provide strategies, provide solutions. We don’t want to just blame government or blame China. As individuals here we need to do something ourselves, be activists, rather than just being the taker and blaming it on everyone else,” she said.

Lee said she was not daunted by the scale of the problem.

“I am doing what I can do. That is the thing I believe in, freedom, democracy… that’s the value I want to leave for the future.”

The Detail emailed the Chinese Embassy in Wellington with questions but got no response.

The trip to Taiwan was hosted and funded by its Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Check out how to listen to and follow The Detail here.

You can also stay up-to-date by liking us on Facebook

– Published by EveningReport.nz and AsiaPacificReport.nz, see: MIL OSI in partnership with Radio New Zealand