Source: The Conversation – UK – By Simon Goodman, Associate professor, De Montfort University

Keir Starmer has called on Nigel Farage to address allegations of racism in Reform UK, and antisemitic and xenophobic comments and bullying allegedly made by Farage while he was at school. Farage has denied the accusations.

A few weeks before the allegations about Farage emerged, Reform MP Sarah Pochin was accused of racism after saying that it “drives me mad when I see adverts full of black people, full of Asian people”. Farage said that while Pochin’s comments were “ugly”, they did not amount to racism, explaining: “If I thought that the intention behind it was racist, I would have taken a lot more action than I have to date. And that is because I don’t.”

This reaction suggests that, to some extent, it is still a taboo to be seen as racist. But is this taboo losing its strength? As scholars of the social psychology of racism, we think so.

In a recent interview, health secretary Wes Streeting noted that rising racism faced by NHS staff was similar to the “ugly” racism of the 1970s and 80s in the UK.

Streeting made the worrying claim it had now become “socially acceptable to be racist”. Hate crime statistics and other reports support this idea and suggest racism is widespread. Quotes in news reports have echoed the idea that the present climate is reminiscent of overt and violent racism of the recent past.

Social psychologists have shown that people generally do not want to come across as prejudiced. Academic Michael Billig describes this as the “norm against prejudice”.

The overtness of racism and its social acceptability are intertwined. Subtle or hidden racism, by its nature, is hard to call out and easy to deny, so in effect becomes socially acceptable in many situations. Overt racism, on the other hand, breaches common understandings – norms – that racism is wrong.

Anti-immigration

Much research has shown how talk about restricting migration is regularly argued to be prejudiced or racist. Historically, calls for restricting migrants, in the UK at least, have been about excluding ethnic and racial outgroups like Jews, black and brown people or eastern Europeans.

However, because of the norm against prejudice, people typically do not offer openly derogatory descriptions of migrants, such as that they are sexual deviants, lazy, or are inferior to the resident population. However, some high-profile figures and their supports are, arguably, increasingly comfortable doing so.

In 2011, scholar Frank Reeves examined political discourse about race in the House of Commons in the context of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act. His research showed how MPs would frame calls for stricter migration in terms of problematic race relations between black and “resident” or white populations, instead of saying anything about the supposed superiority of white people.

Similar findings are noted across parliaments in the UK, Australia and Europe, where immigration controls are routinely argued for and justified in terms that do not make racism explicit.

But the current situation suggests this is changing. Anti-migrant protests and demonstrations in the UK show that migrants and refugees are being directly demonised, often from a racist, religous or ethno-nationalist viewpoint. This has included calls to deport asylum seekers and migrants, irrespective of their legal status in the UK, and demonising Islam and cultures that are allegedly not “British”.

Weakening norms

In the last few months, overt anti-migrant racism targeting non-white people has become public around the world, as seen in the riots and racist attacks in Ireland, Australia and the Netherlands. In the UK, attacks on mosques and migrant properties are not unheard of.

In September 2025, the UK saw its largest ever far-right march, the “Unite the Kingdom” rally. Several of the speakers openly called for the removal of migrants or foreigners in the UK, and to transform it into a Christian nation. Such claims could readily be seen as racist.

But for many others on the march, the norm against prejudice appeared to be in operation. When interviewed, people largely gave specific reasons for why they had attended these protests or, to them, why it was okay (and perhaps necessary) to protest.

Racism as a political tool

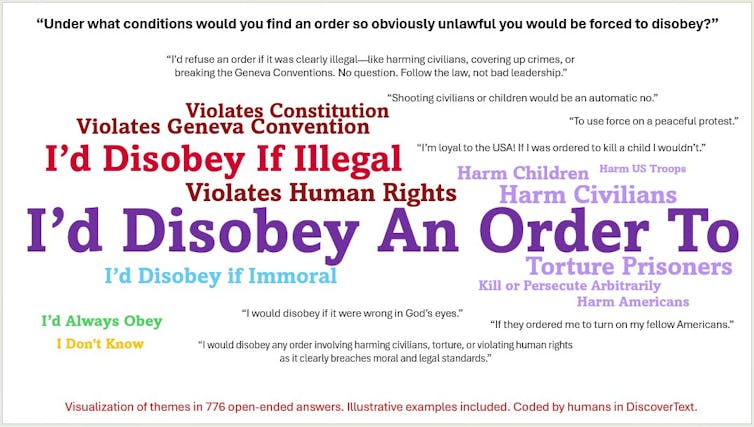

Accusations of racism are still taboo and treated as unfair labelling. But psychology professor Kevin Durrheim and colleagues have shown how the norm against prejudice is weakening in rightwing populist spaces.

The researchers illustrated this point with a comment from a supporter of Farage during the UKIP years: “I see uncontrolled immigration when I look around. If that makes me racist then so be it. I live in a predominantly racist country (many people share my view) so be it. If you want to call me a racist then go ahead, but please don’t try to tell me up is down and down is up.”

Other research shows that radical right politicians sometimes deal with accusations that they are racist by embracing it and using it to present themselves and their supporters as targets.

It is not a precondition for the rise of the far right that norms against prejudice are weakened, but it does make it harder to challenge. If it is no longer a problem to be viewed as prejudiced, then intimidating marginalised others and calling for deportations becomes easier.

![]()

Simon Goodman receives funding from the ESRC and the British Academy

Rahul Sambaraju receives funding from British Academy.

– ref. Is racism becoming more acceptable in the UK? – https://theconversation.com/is-racism-becoming-more-acceptable-in-the-uk-269838