Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Celine Latulipe, Professor, Computer Science, University of Manitoba

Filing taxes every year is an important and necessary task in Canada. But for many, tax preparation and filing can be overwhelming. One reason is that tax forms can sometimes be hard to interpret, especially because most people only deal with them once a year.

Another factor is the shift to digital: tax forms are often delivered electronically; tax software has become the preferred method for tax preparation and filing; and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) prefers to send all tax information electronically through the CRA MyAccount.

With this digital system, it’s typically necessary to access tax forms and previous Notices of Assessment by logging in to your CRA MyAccount. This can be a barrier for those with less experience using computers and online accounts, such as some older adults.

Many people act as informal tax helpers by filing taxes for older parents, relatives or friends. In fact, half of Canadians filing taxes have someone else do their taxes for them. Of those, one in five reports getting help from a friend or family member acting as an informal tax helper.

This means about 10 per cent of tax filers in Canada rely on family or friends to file their taxes. The CRA has a Represent a Client program that allows informal tax helpers to log in to the CRA MyAccount of the person they are helping to access relevant tax forms. However, a study that I recently conducted with colleauges shows that this mechanism is under-utilized.

How informal tax helpers access CRA accounts

Getting help with taxes can take many forms: hiring an accountant, visiting a tax preparation company, getting help from a volunteer through the Canadian Volunteer Income Tax Program (CVITP) or delegating to an informal tax helper.

Tax accountants, tax preparers and CVITP volunteers have business IDs or Group IDs for accessing CRA MyAccounts of the clients they assist. Similarly, informal tax helpers can sign up with CRA’s Represent a Client program to get RepIDs, which are ID numbers provided by the CRA to people whose identity is verified by having their own CRA MyAccount.

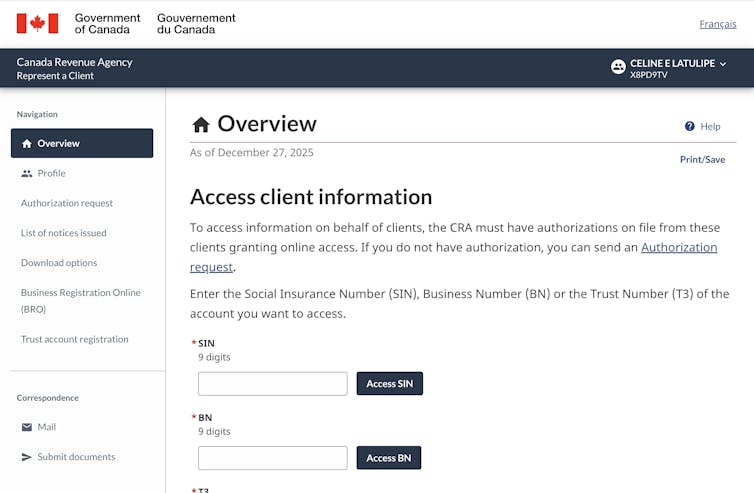

As an example, having a RepID allows me to access my daughter’s CRA MyAccount to get her Notices of Assessments, download tax forms and use NetFile to file her taxes. I could ask my daughter to log in and download those items for me, but it is faster for me to do it, as I know what forms I’m looking for and where to find them.

(Canada Revenue Agency)

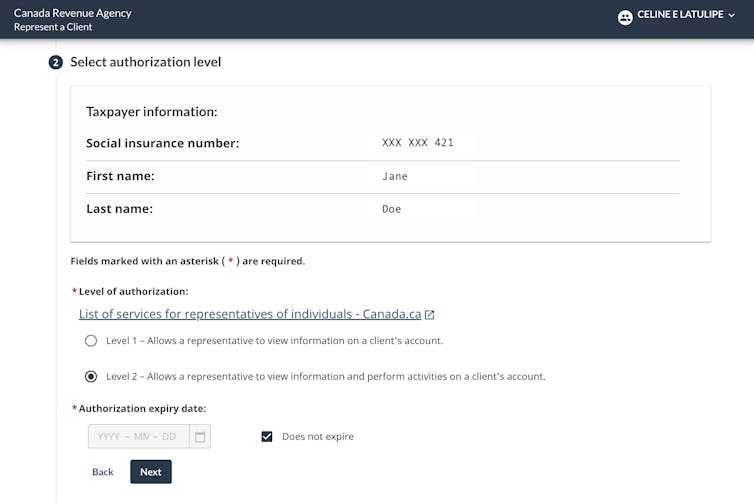

Having a RepID does not give access to everyone’s tax records. A link needs to be established between the helper’s RepID and the CRA MyAccount of the person they are assisting. This can be done by uploading a signed form from the taxpayer or by sending an authorization request through the CRA system, which the taxpayer must approve.

The risks of sharing login credentials

In our study, we investigated CRA delegation mechanisms. We conducted a semi-structured interview study with 19 participants, including older adults, formal tax volunteers and informal tax helpers, to understand the challenges and experiences of tax delegation.

We found that only one informal tax helper used a RepID. Most either did everything using paper forms provided by the person they are helping, or they accessed that person’s CRA MyAccount using that individual’s credentials to log in.

In some cases, informal tax helpers may actually be setting up the CRA MyAccounts for the people they are helping, which means they know the login credentials. This violates the terms of service of the CRA MyAccount — you are not supposed to share your password with anyone.

Read more:

Password sharing is common for older adults — but it can open the door to financial abuse

While informal tax helpers are providing a valuable and helpful service to their friends and families, using a person’s credentials to access their CRA MyAccounts is problematic.

When an informal tax helper knows someone else’s CRA login credentials, they could log in as that user, change the mailing address and banking deposit details, and then make bogus tax and benefit claims. In this case, the CRA has no way to tell that it is someone else logging in and taking actions on behalf of the taxpayer associated with the account.

However, if an informal tax helper uses a RepID to access someone’s CRA MyAccount, the CRA knows exactly who is doing what. They don’t allow informal tax helpers to change the mailing address or bank deposit information, which goes a long way to preventing tax fraud.

Make tax help safer with a CRA RepID

If someone is helping you file your taxes, ask them to get a CRA RepID. It’s a quick process for them, and then they can access tax forms in your CRA MyAccount safely. This way, the CRA will know when it is them signing in to your account versus you, and your helper will only be able to access the appropriate functions.

(Canada Revenue Agency)

Most informal tax helpers are honest, helpful people and they shouldn’t have to impersonate you to get your taxes done. Using the CRA’s Represent a Client system provides legitimacy to informal tax helpers and safety for those getting assistance.

With the tax deadline of April 30, 2026 approaching, if you plan to have someone assist you with tax filing, it’s a good time to check with them to make sure they use a RepID to access your CRA MyAccount. Doing this early can help avoid last-minute stress, ensure your tax return is filed accurately and give you confidence that your information is secure.

![]()

Celine Latulipe receives funding from NSERC.

– ref. Filing taxes for someone else? Here’s how to do it safely – https://theconversation.com/filing-taxes-for-someone-else-heres-how-to-do-it-safely-271924