Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By George Kassar, Full-time Faculty, Research Associate, Ascencia Business School

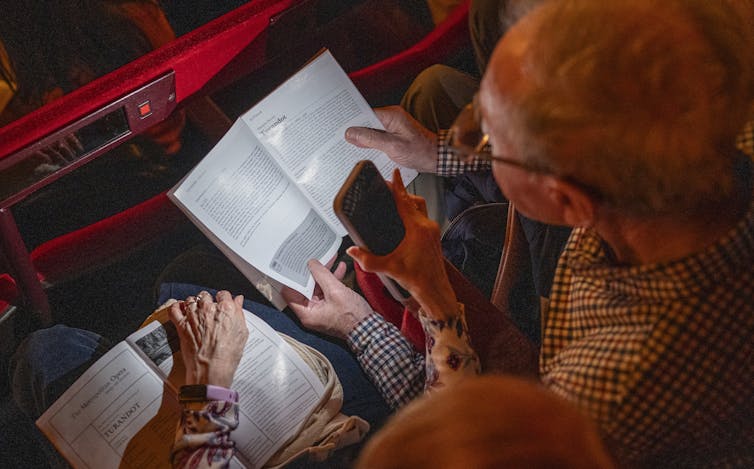

Nous sommes bel et bien en janvier. Le mois du blanc est surtout celui du grand théâtre des entretiens d’évaluation individuelle de performance dans bien des entreprises. Alors, comment les cadrer au mieux pour distinguer les salariés qui se mettent en scène de ceux qui créent réellement de la valeur, mais sous-estiment leur capacités ?

L’entretien annuel de performance est devenu un passage obligé dans la plupart des organisations. Il ne s’agit pas d’une simple discussion informelle, mais d’un moment qui pèse sur les primes, les promotions ou les opportunités de carrière. Très différent des entretiens de parcours professionnels qui sont une obligation légale, les salariés y voient un verdict sur leur année ; les managers doivent trancher, classer, justifier. La pression est forte des deux côtés de la table.

Dans ce contexte tendu, le collaborateur entre, armé de son powerpoint mental avec ses objectifs atteints, ses initiatives personnelles ou son leadership exemplaire. Le manager, lui, soucieux de préserver l’éthique dans ce processus, coche des cases, écoute poliment et note des mots-clés : confiance, dynamisme, vision, etc. Tout semble sérieux, objectif, quantifié. En réalité, la scène tient parfois plus du théâtre qu’une vraie application scientifique de la gestion de la performance.

De ce fait, ces entretiens, pourtant censés évaluer les résultats concrets, finissent souvent par mesurer autre chose, celle de la capacité à se vendre. Ce glissement ne serait qu’un détail s’il n’avait pas de conséquences bien réelles sur la motivation et la rétention des « talents ».

Quand la confiance se déguise en compétence

Durant le mois de janvier, un paradoxe managérial devient presque une tradition. Ceux qui maîtrisent tout juste leur sujet arrivent sûrs d’eux, brandissant leurs « grandes réussites » et occupent l’espace. Les vrais compétents, eux, minimisent leurs exploits, soulignent ce qui reste à améliorer… et passent sous le radar. Résultat : on récompense ceux qui parlent le plus fort, pas forcément ceux qui contribuent le plus. On s’étonne ensuite de voir les meilleurs partir.

Le phénomène a un nom : l’effet Dunning-Kruger. Décrit dès 1999 par les psychologues David Dunning et Justin Kruger, il désigne la tendance des moins compétents à surestimer leurs capacités tandis que les plus compétents se montrent plus prudents dans leur jugement.

Les études contemporaines confirment que ce biais ne s’arrête pas à la salle de classe, au laboratoire ou même sur le champ. Transposé au bureau, ce syndrome donne une situation paradoxale : plus on est limité, plus on risque de se croire excellent, plus on est bon, plus on doute et plus on voit ce qui pourrait être mieux.

Marketing de soi-même

Si le manager ne s’appuie que sur le discours tenu pendant l’entretien, sans preuves solides, il a toutes les chances de se laisser influencer par cette confiance parfois mal placée. L’aisance orale, la capacité à « vendre » un projet ou à reformuler ses tâches en succès stratégiques deviennent des critères implicites d’évaluation.

Cette surestimation omniprésente pourrait entraîner de graves atteintes au bon jugement professionnel. Elle déforme la perception des compétences réelles et favorisent une culture d’apparence plutôt qu’une culture de résultats.

Les vrais performants, souvent modestes, finissent par comprendre que la reconnaissance interne ne récompense pas les résultats et l’impact de leur travail, mais le récit qu’on en fait et la capacité à se mettre en scène.

Ces derniers peuvent ressentir un décalage entre ce qu’ils apportent réellement et ce que l’organisation valorise. Leur engagement s’érode, leur créativité aussi. Ce qui est un facteur bien documenté de démotivation et de départ.

Le plus ironique ? Ceux qui doutent d’eux-mêmes sont souvent ceux qu’on aimerait garder. Les études sur la métacognition montrent que la capacité à se remettre en question est un signe de compétence. À l’inverse, les plus sûrs n’évoluent pas. Persuadés d’avoir déjà tout compris, ils s’enferment dans leur propre suffisance durable.

L’entreprise perd, dans le silence, celles et ceux qui faisaient avancer les projets les plus exigeants et les plus sensibles. Elle garde ceux qui savent surtout parler de leurs succès.

Cadrer l’évaluation sur des faits

La bonne nouvelle est qu’il est possible de corriger cette dérive. Les pistes sont connues mais rarement appliquées.

Tout commence par un bon cadre pour la mise en place de l’évaluation de la performance. Une formation adaptée aux managers, évaluateurs et collaborateurs est encouragée, avec un système de revue fréquente de la performance, un dispositif de mesure clairement défini et un groupe d’évaluateurs multiples.

À lire aussi :

Parler salaires, un tabou en France ? Vraiment ?

Il est important de fonder les évaluations sur des faits en revenant à des concepts fondamentaux tels que le management by objectives (MBO). L’enjeu : définir des objectifs clairs, mesurables, ambitieux mais réalistes, suivi à l’aide d’indicateurs alignés sur l’impact réel, avec une stratégie de mesure fondée sur les données pour évaluer des résultats concrets, et pas seulement le récit de la personne évaluée.

L’avis d’un seul manager ne devrait pas suffire à juger la performance d’une personne qui travaille en équipe. Il faut regarder sa contribution au collectif.

Les dispositifs de « feed-back à 360° » permettent de diversifier les retours

– collègues, clients, revues de projets, etc. Quand plusieurs personnes confirment la contribution d’un collaborateur discret, il devient plus difficile de l’ignorer. À l’inverse, un profil très visible mais peu fiable sera plus vite repéré.

Distinguer assurance et compétence

Il est important de garder à l’esprit que la gestion de la performance est un processus social. Les recherches montrent que le feed-back formel, donné lors de l’entretien annuel, est bien plus efficace lorsqu’il est soutenu par un feed-back informel et des échanges réguliers. Ces discussions spontanées renforcent la confiance et créent le contexte nécessaire pour que l’évaluation finale soit juste, non biaisée, acceptée et réellement utile.

Il est essentiel de former les managers à mieux reconnaître et anticiper les biais cognitifs, en particulier ceux du jugement, dont le fameux décalage entre confiance affichée et compétence réelle. Comprendre que l’assurance n’est pas une preuve en soi, et que la prudence peut être le signe d’une réelle expertise, change la manière de conduire un entretien.

Tant que les entreprises confondront assurance et compétence, elles continueront à promouvoir les plus confiants et à perdre, peu à peu, leurs meilleurs éléments.

Dans un marché où les talents ont le choix, ce biais n’est pas qu’un détail psychologique : mais un véritable risque stratégique. Après tout, ceux qui parlent le plus fort ne sont pas toujours ceux qu’il faudrait écouter !

![]()

George Kassar ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Entretien annuel : le danger du marketing de soi – https://theconversation.com/entretien-annuel-le-danger-du-marketing-de-soi-271897