Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Lachlan Goold, Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Music, University of the Sunshine Coast

Ozzy Osbourne, the “prince of darkness” and godfather of heavy metal, has died aged 76, just weeks after he reunited with Black Sabbath bandmates for a farewell concert in his hometown of Birmingham in England.

His family posted a brief message overnight: “It is with more sadness than mere words can convey that we have to report that our beloved Ozzy Osbourne has passed away this morning.”

John Michael Osbourne changed the sound of rock music and leaves behind a stellar career spanning six decades, numerous Grammy awards, multiple hall of fame inductions – and a wave of controversy.

An agent of change

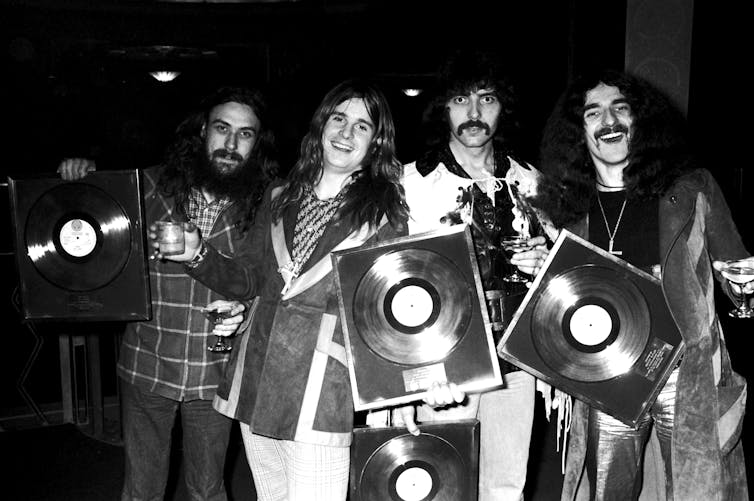

In 1969, from the ashes of various bands, Geezer Butler (bass), Tony Iommi (guitar), Bill Ward (drums) and Osbourne formed the band Earth.

Realising the name was taken, they quickly changed their name to Black Sabbath, an homage to the 1963 Italian horror anthology film.

With the Summer of Love a recent memory, Black Sabbath were part of a heavy music revolution, providing an antidote to the free loving hippies of the late 60s period.

Despite making their first two albums cheaply, Black Sabbath, released in February 1970, and Paranoid, released September that same year, they were a global success.

Their approach was laden with sarcasm and irony. American audiences mistook this for satanic worship, positioning them as outsiders (albeit popular ones).

Michael Putland/Getty Images

After Black Sabbath’s early successes, they were managed by the notorious Don Arden, whose daughter Sharon Levy was the receptionist. More than any musical bond Osbourne had in his life, Sharon would be the most influential character throughout his life.

Osbourne recorded eight albums with Black Sabbath (some to critical acclaim) and was then kicked out (by Sharon) due to his troubles with drugs and alcohol.

Ozzy solo

Osbourne’s solo career has always been managed by Sharon. While recording his second solo album, Diary of a Madman, guitarist Rhodes died in a tragic light plane crash. Osbourne was close to Rhodes and fell into a deep depression, after never having lost someone so close.

Sharon and Osbourne married only months after this incident. His struggle with drug use did not stop him from making further solo records alongside various guitar players, continuing with moderate success throughout his career.

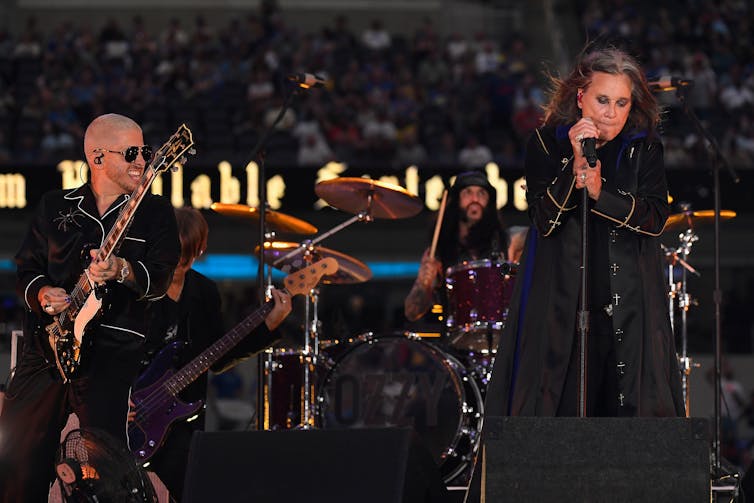

On the road, Osbourne put the John Farnham’s last tour trope to shame.

He held his last ever gig more times than one can count with names like No More Tours (1992–93), Retirement Sucks (1995–96) and No More Tours 2 (2018–19).

Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

This lament for touring led to the most successful era of Osbourne’s career. After being rejected for the 1995 Lollapaloza festival bill, Sharon (and their son Jack) started Ozzfest; initially an annual two-day multiband festival headlined by Osbourne, held in Phoenix, Arizona, and Devore, California.

Subsequently becoming a national – and then international – tour, Ozzfest led to a successful partnership with MTV, which led to the reality TV show The Osbournes premiering in 2002. Here, his previous and ongoing battle with drugs was obvious, proudly on display – and ridiculed – to huge global audiences.

The spectacle of a rich rockstar and his family featured a constant barrage of swearing, battles with lavish TV remotes, canine therapy, never-ending chaos, and Osbourne constantly yelling “Sharrrooon” like a twisted maniacal loop of A Street Car Named Desire.

Struggles and controversies

Osbourne suffered multiple health conditions over the years, rarely concealing the state of his physical or mental wellbeing.

Notably he’s struggled with drug and alcohol abuse his whole career with drug recovery centres using Osbourne as an exemplar. In 2007 he disclosed he suffered from the Parkinson’s adjacent condition Parkinsonian syndrome. In 2019 he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Chris Walter/WireImage

This resulted in him being unable to walk for his final Back to the Beginning show in Birmingham on July 5 2025.

And Osbourne’s career had more than its fair share of controversy. He bit the head off a dove and a bat (celebrated with a commemorative toy), and urinated on the Alamo cenotaph. He was taken to court multiple times, but was never convicted.

Ozzy and me

As a white middle-class boy growing up in the Brisbane suburbs in the 80s, heavy metal music appealed to my testosterone and pimple filled body.

Exploring the secondhand record shops of Brisbane, I would’ve bought my first copy of Black Sabbath around 1985. The sound of thunder and a distant church bell before the first drop-D riff enters seemed like the antithesis to sunny Queensland and 80s pop.

As my life became obsessed with the recording studio and the vociferous music scene in Brisbane in the post-Joh era, and those drop-D riffs influenced a new style that swept the world in the early 90s.

Osbourne’s influence was huge and through grunge, his sound was reborn. Grunge was a marriage of the Sabbath-like drop-D riffs with the energy of punk and the melody of the Beatles.

Listening to Black Sabbath and Ozzy records, equipped me with a sonic palette ready to capture the wave of alternative music emmerging from the Brisbane scene.

While Ozzy’s death is no surprise (except for those who never thought he’d last this long), we should take pause and remember an icon with an endless energy for entertaining, a passion for music, and changing the expectations of popular culture for more than 50 years.

![]()

Lachlan Goold does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The incredible impact of Ozzy Osbourne, from Black Sabbath to Ozzfest to 30 years of retirement tours – https://theconversation.com/the-incredible-impact-of-ozzy-osbourne-from-black-sabbath-to-ozzfest-to-30-years-of-retirement-tours-258820