Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Arindam Sau, Ph.D. Candidate in Chemistry, University of Colorado Boulder

Manufactured chemicals and materials are necessary for practically every aspect of daily life, from life-saving pharmaceuticals to plastics, fuels and fertilizers. Yet manufacturing these important chemicals comes at a steep energy cost.

Many of these industrial chemicals are derived primarily from fossil fuel-based materials. These compounds are typically very stable, making it difficult to transform them into useful products without applying harsh and energy-demanding reaction conditions.

As a result, transforming these stubborn materials contributes significantly to the world’s overall energy use. In 2022, the industrial sector consumed 37% of the world’s total energy, with the chemical industry responsible for approximately 12% of that demand.

Conventional chemical manufacturing processes use heat to generate the energy needed for reactions that take place at high temperatures and pressures. An approach that uses light instead of heat could lower energy demands and allow reactions to be run under gentler conditions — like at room temperature instead of extreme heat.

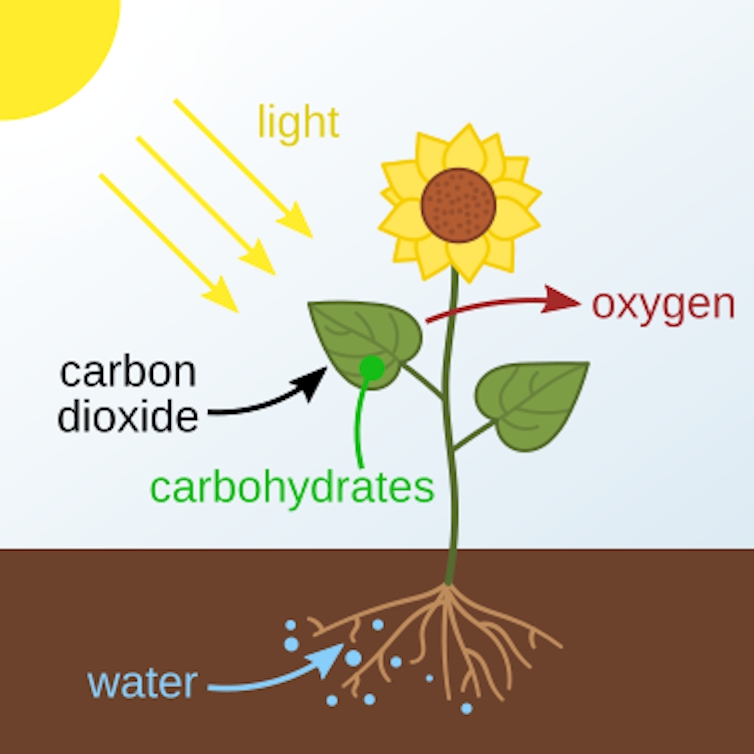

Sunlight represents one of the most abundant yet underutilized energy sources on Earth. In nature, this energy is captured through photosynthesis, where plants convert light into chemical energy. Inspired by this process, our team of chemists at the Center for Sustainable Photoredox Catalysis, a research center funded by the National Science Foundation, has been working on a system that uses light to power reactions commonly used in the chemical manufacturing industry. We published our results in the journal Science in June 2025.

We hope that this method could provide a more economical route for creating industrial chemicals out of fossil fuels. At the same time, since it doesn’t rely on super-high temperatures or pressures, the process is safer, with fewer chances for accidents.

Wattcle, Nefronus/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

How does our system work?

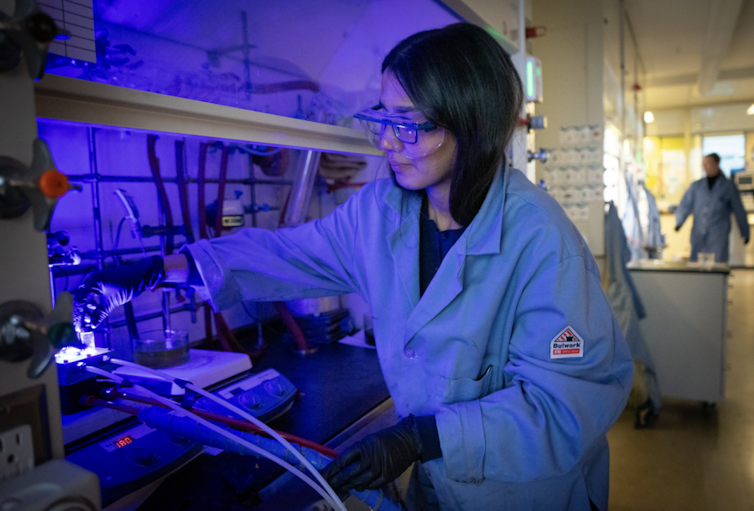

The photoredox catalyst system that our team has developed is powered by simple LEDs, and it operates efficiently at room temperature.

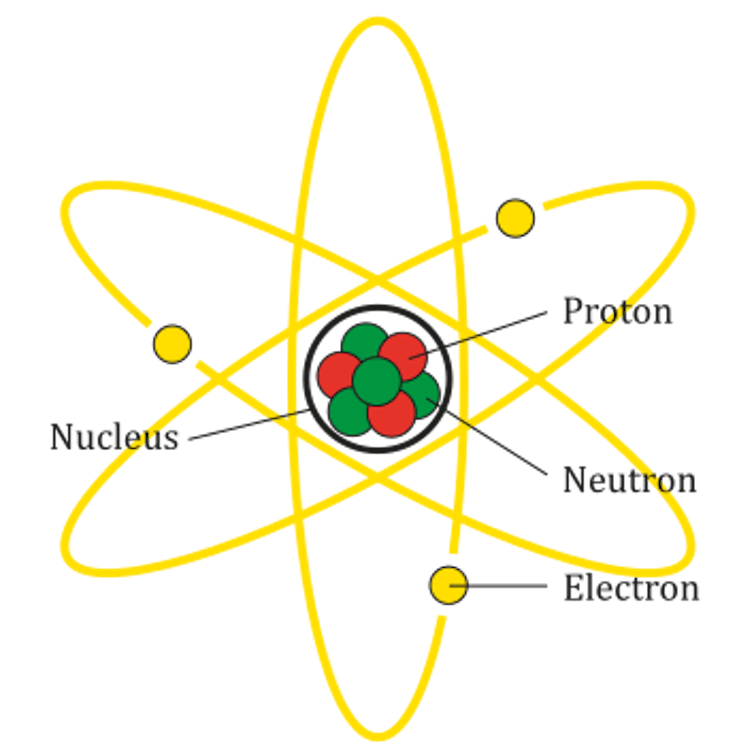

At the core of our system is an organic photoredox catalyst: a specialized molecule that we know accelerates chemical reactions when exposed to light, without being consumed in the process.

Much like how plants rely on pigments to harvest sunlight for photosynthesis, our photoredox catalyst absorbs multiple particles of light, called photons, in a sequence.

These photons provide bursts of energy, which the catalyst stores and then uses to kick-start reactions. This “multi-photon” harvesting builds up enough energy to force very stubborn molecules into undergoing reactions that would otherwise need highly reactive metals. Once the reaction is complete, the photocatalyst resets itself, ready to harvest more light and keep the process going without creating extra waste.

Designing molecules that can absorb multiple photons and react with stubborn molecules is tough. One big challenge is that after a molecule absorbs a photon, it only has a tiny window of time before that energy fades away or gets lost. Plus, making sure the molecule uses that energy the right way is not easy. The good news is we’ve found that our catalyst can do this efficiently at room temperature.

John Cline, Colorado State University Photography

Enabling greener chemical manufacturing

Our work points toward a future where chemicals are made using light instead of heat. For example, our catalyst can turn benzene — a simple component of crude oil — into a form called cyclohexadienes. This is a key step in making the building blocks for nylon. Improving this part of the process could reduce the carbon footprint of nylon production.

Imagine manufacturers using LED reactors or even sunlight to power the production of essential chemicals. LEDs still use electricity, but they need far less energy compared with the traditional heating methods used in chemical manufacturing. As we scale things up, we’re also figuring out ways to harness sunlight directly, making the entire process even more sustainable and energy-efficient.

Right now, we’re using our photoredox catalysts successfully in small lab experiments — producing just milligrams at a time. But to move into commercial manufacturing, we’ll need to show that these catalysts can also work efficiently at a much larger scale, making kilograms or even tons of product. Testing them in these bigger reactions will ensure that they’re reliable and cost-effective enough for real-world chemical manufacturing.

Similarly, scaling up this process would require large-scale reactors that use light efficiently. Building those will first require designing new types of reactors that let light reach deeper inside. They’ll need to be more transparent or built differently so the light can easily get to all parts of the reaction.

Our team plans to keep developing new light-driven techniques inspired by nature’s efficiency. Sunlight is a plentiful resource, and by finding better ways to tap into it, we hope to make it easier and cleaner to produce the chemicals and materials that modern life depends on.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Light-powered reactions could make the chemical manufacturing industry more energy-efficient – https://theconversation.com/light-powered-reactions-could-make-the-chemical-manufacturing-industry-more-energy-efficient-257796