Source: The Conversation – in French – By Jie Yu, Doctorat en art numérique, danse et patrimoine immatériel, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT)

Est-il possible de danser les forêts et territoires de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue ? Est-il possible que ces territoires aient une danse qui soit la leur ? Dans le cadre de mes recherches, je m’efforce justement d’éclairer ces questions, de favoriser les rencontres et partages entre le corps et la nature.

La pratique somatique, autrement dit la danse, puis les paysages culturels et naturels, sont souvent séparés, et ce pour plusieurs raisons. Il m’apparaît néanmoins, à la suite d’autres chercheurs et artistes, que leur mise en rapport ouvre de riches perspectives théoriques et artistiques.

En tant qu’artiste-chercheur, mon travail se situe à l’intersection de la danse, de l’art numérique et de l’anthropologie culturelle. Je cherche à créer des ponts entre les cultures et les territoires.

Le présent article se propose d’éclairer comment les outils numériques peuvent être utilisés pour capturer et retracer les particularités d’un paysage culturel, lesquelles particularités peuvent ensuite nourrir une pratique somatique.

Déjà des milliers d’abonnés à l’infolettre de La Conversation. Et vous ? Abonnez-vous gratuitement à notre infolettre pour mieux comprendre les grands enjeux contemporains.

À la rencontre de nouveaux territoires

Mon projet prend place dans le territoire d’Abitibi-Témiscamingue, plus précisément dans le parc Kiwanis à Rouyn-Noranda, un lieu riche en interactions entre l’environnement et les sociétés humaines.

Dans le cadre de mes recherches, je considère les interactions entre la nature et l’humain comme constituant un « paysage culturel », que je retrace en fusionnant les pratiques somatiques et les traditions culturelles locales.

Par exemple, lors de ma rencontre avec Valentin Foch, membre du collectif à l’origine du projet La forêt numérique, j’ai observé comment leur approche interactive redéfinit la relation entre l’humain et son environnement à travers des installations immersives et des projections numériques qui mettent en valeur les paysages forestiers et la biodiversité régionale.

En articulant à mon tour ma réflexion aux paysages naturels locaux, je m’efforce à partir de mon propre patrimoine culturel d’envisager des dialogues entre la nature, le corps et l’art numérique.

La méthodologie de ce projet repose sur une approche en quatre étapes.

1. Recherche sur le terrain

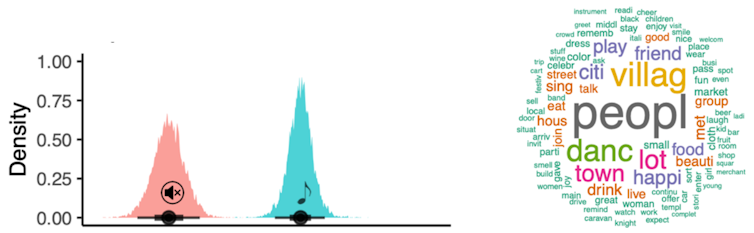

Le travail de terrain au parc Kiwanis a débuté par une exploration systématique de l’environnement naturel. Il s’agissait d’observer la végétation, les cycles saisonniers et les dynamiques naturelles spécifiques à ce territoire. J’ai ainsi pu documenter la transformation des arbres au fil des saisons, ou les variations des couleurs et des textures des sols.

Ces observations m’ont permis d’identifier des éléments caractéristiques du paysage, tels que les mouvements répétitifs des branches sous l’effet du vent, ou le rythme des vagues sur le lac.

Le but de ma recherche consiste ensuite à traduire ces divers éléments en gestes corporels précis et reproductibles, lesquels pourront ensuite être intégrés dans ma pratique somatique.

2. Pratique somatique sur le terrain

La pratique somatique sur le terrain s’appuie sur une série d’exercices structurés visant à explorer les interactions physiques et sensorielles entre le corps et l’environnement naturel.

Chaque séance commence par une immersion complète dans le paysage, où l’observation et la sensation jouent un rôle clé. Cette étape inclut l’identification des éléments spécifiques de l’environnement, comme la direction et la vitesse du vent, la texture du sol ou les mouvements des végétaux, qui influencent directement les choix de mouvements.

Cette méthode intègre également des pauses réflexives, lors desquelles je m’assieds ou me tiens immobile pour observer comment mon corps s’adapte aux stimuli ambiants. Ces moments permettent de capturer des réactions instinctives ou inconscientes, qui enrichissent ensuite la gestuelle chorégraphique.

Ainsi, le corps devient un interprète actif du paysage.

3. La pratique écosomatique

L’écosomatique, un concept développé par le chercheur australien Raffaele Rufo, constitue un cadre essentiel dans ma démarche.

Cette approche explore comment les cycles naturels et les phénomènes écologiques influencent les expériences corporelles. Dans ce contexte, chaque mouvement réalisé sur le terrain est conçu pour refléter ou dialoguer avec les processus naturels observés, qu’il s’agisse du balancement des branches, de la progression des vagues ou des sons environnants.

Dans le cadre de mes recherches, j’ai approché l’écosomatique à partir de mon patrimoine culturel, soit le Tai-Chi et les danses folkloriques orientales. Le Tai-Chi, basé sur des mouvements circulaires et fluides, m’a permis de développer une gestuelle en harmonie avec les dynamiques naturelles du parc Kiwanis.

Par exemple, les postures d’ouverture des bras et les rotations du torse sont adaptées pour refléter la trajectoire des branches balancées par le vent.

Les danses folkloriques orientales, quant à elles, offrent une perspective culturelle unique pour enrichir les mouvements chorégraphiques. Ces danses, souvent inspirées par des éléments naturels comme les rivières, les montagnes ou les saisons, ont été adaptées pour correspondre aux caractéristiques spécifiques du paysage québécois.

En combinant ces traditions avec les observations directes du terrain, j’ai développé des mouvements qui transcendent les frontières géographiques et culturelles. Ces gestes traduisent non seulement les particularités de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue, mais établissent également un pont entre les philosophies orientales et occidentales.

Chorégraphie et art numérique : une expérience immersive

La chorégraphie développée dans le cadre de cette recherche repose sur une analyse détaillée des interactions entre le corps humain, les éléments naturels et les traditions culturelles.

Le processus débute par une déconstruction des mouvements naturels observés pour en identifier les motifs récurrents. Par exemple, les mouvements des arbres agités par le vent ont été analysés pour isoler des séquences spécifiques, telles que des balancements rythmiques ou des rotations lentes. Ces éléments ont ensuite été traduits en gestes corporels, intégrant des transitions fluides pour capturer la continuité observée dans la nature.

L’aspect numérique de ce projet, intitulé Module d’excursion, repose sur l’utilisation de la technologie de capture de mouvement (MoCap). En portant des capteurs placés stratégiquement sur différentes parties du corps, mes mouvements chorégraphiques sont enregistrés avec précision. En outre, cette approche numérique facilite l’archivage et la transmission des pratiques chorégraphiques.

Vidéo-danse et transmission interculturelle

Dans le cadre de cette recherche-création, j’ai réalisé une vidéo-danse qui met en dialogue mes origines culturelles bouyei et l’environnement québécois du parc Kiwanis. Le processus de création a combiné des choix chorégraphiques précis, une mise en scène réfléchie et des techniques de captation visuelle.

Cette vidéo-danse dépasse la simple performance artistique : elle constitue un outil de transmission culturelle. En intégrant des éléments concrets des traditions bouyei et québécoises dans un format visuel et accessible, elle offre un moyen de sensibiliser différents publics à l’importance de préserver et d’honorer le patrimoine culturel immatériel.

À lire aussi :

Construire un pont culturel entre le Québec et un peuple asiatique méconnu

En outre, cette œuvre devient non seulement une performance visuelle, mais aussi un dialogue interculturel vivant et un témoignage de la coexistence harmonieuse entre tradition et innovation.

Retombées concrètes et rayonnement

Le projet Module d’excursion a eu un impact non négligeable tant au niveau local qu’international. Après sa première projection publique au Petit Théâtre du Vieux Noranda, ce projet a été présenté à l’Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), attirant un large public universitaire.

Le succès de ces projections, ainsi que la reconnaissance du deuxième prix au Concours mondial d’art-thérapie en janvier 2023, témoignent de la portée et de la pertinence de cette démarche artistique.

Le projet a également reçu de la visibilité en Chine. Sa présentation au 90ᵉ Congrès de l’Acfas en avril 2023 et son prix Régal de la ville de Rouyn-Noranda en novembre 2024 illustrent l’impact de cette initiative sur la scène culturelle locale.

![]()

Jie Yu ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Et si chaque territoire avait sa danse, quelle serait celle des forêts du Québec ? – https://theconversation.com/et-si-chaque-territoire-avait-sa-danse-quelle-serait-celle-des-forets-du-quebec-246215