Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By Emmanuel Carré, Professeur, directeur de Excelia Communication School, chercheur associé au laboratoire CIMEOS (U. de Bourgogne) et CERIIM (Excelia), Excelia

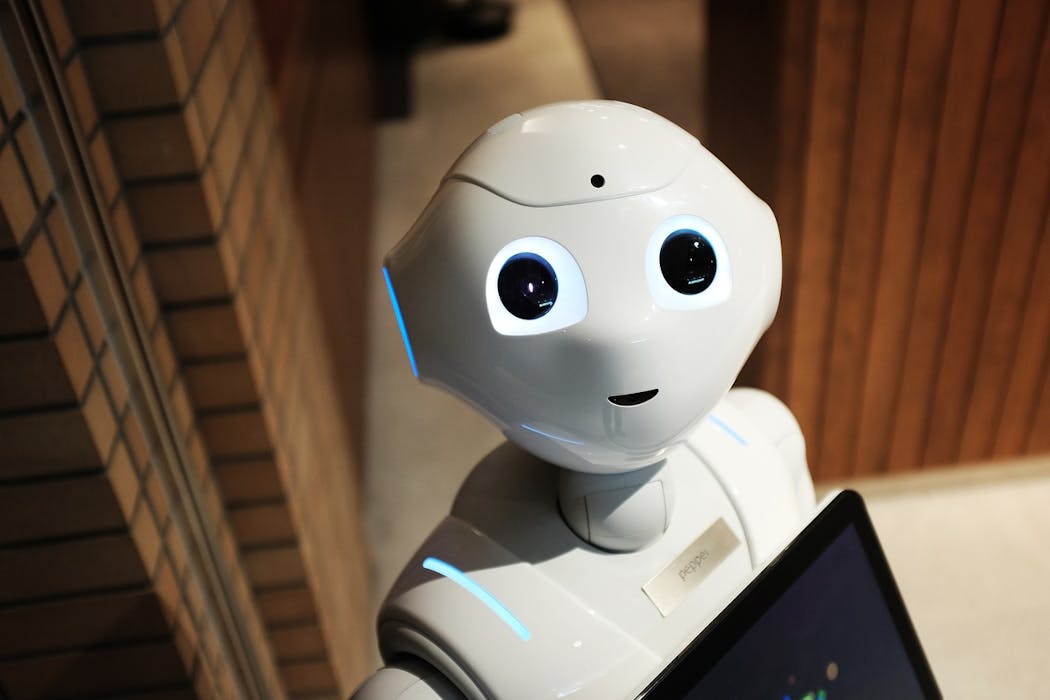

Les intelligences artificielles qui donnent l’impression de comprendre nos émotions se multiplient. Sur Replika ou Snapchat AI, des millions de personnes dialoguent chaque jour avec ces systèmes conçus pour écouter et rassurer. Les modèles de langage, comme ChatGPT, Claude ou Gemini, prolongent cette tendance : leurs réponses empreintes d’approbation et d’enthousiasme instaurent une convivialité programmée qui finit par façonner une norme de dialogue aussi polie qu’inquiétante.

Le psychologue américain Mark Davis définit l’empathie comme la capacité à percevoir les états mentaux et émotionnels d’autrui, à s’y ajuster et à en tenir compte dans sa conduite. Les chercheurs distinguent deux versants : l’empathie cognitive, fondée sur la compréhension des intentions, et l’empathie affective, liée au partage du ressenti. Cette distinction, centrale en psychologie sociale, montre que l’empathie n’est pas une émotion mais relève d’une coordination interpersonnelle.

Dans la vie quotidienne comme dans les métiers de service, l’empathie structure ainsi la confiance. Le vendeur attentif, le soignant ou le médiateur mobilisent des codes d’attention : ton, regard, reformulation, rythme verbal. Le sociologue Erving Goffman parlait d’« ajustement mutuel » pour désigner ces gestes infimes qui font tenir la relation. L’empathie devient une compétence interactionnelle ; elle se cultive, se met en scène et s’évalue. Les sciences de gestion l’ont intégrée à l’économie de l’expérience : il s’agit de créer de l’attachement par la perception d’une écoute authentique et ainsi d’améliorer la proximité affective avec le consommateur.

Quand les machines apprennent à dialoguer

Le compagnon chatbot Replika revendique 25 millions de personnes utilisatrices, Xiaoice 660 millions en Chine et Snapchat AI environ 150 millions dans le monde. Leur efficacité repose fortement sur la reconnaissance mimétique : interpréter des indices émotionnels pour générer des réponses adaptées.

Dès la fin des années 1990, Byron Reeves et Clifford Nass avaient montré que les individus appliquent spontanément aux machines les mêmes règles sociales, affectives et morales qu’aux humains : politesse, confiance, empathie, voire loyauté. Autrement dit, nous ne faisons pas « comme si » la machine était humaine : nous réagissons effectivement à elle comme à une personne dès lors qu’elle adopte les signes minimaux de l’interaction sociale.

Les interfaces conversationnelles reproduisent aujourd’hui ces mécanismes. Les chatbots empathiques imitent les signes de la compréhension : reformulations, validation du ressenti, expressions de sollicitude. Si j’interroge ChatGPT, sa réponse commence invariablement par une formule du type :

« Excellente question, Emmanuel. »

L’empathie est explicitement mise en avant comme argument central : « Always here to listen and talk. Always on your side », annonce la page d’accueil de Replika. Jusqu’au nom même du service condense cette promesse affective. « Replika » renvoie à la fois à la réplique comme copie (l’illusion d’un double humain) et à la réponse dialogique (la capacité à répondre, à relancer, à soutenir). Le mot suggère ainsi une présence hybride : ni humaine ni objet technique mais semblable et disponible. Au fond, une figure de proximité sans corps, une intimité sans altérité.

De surcroît, ces compagnons s’adressent à nous dans notre langue, avec un langage « humanisé ». Les psychologues Nicholas Epley et John Cacioppo ont montré que l’anthropomorphisme (l’attribution d’intentions humaines à des objets) dépend de trois facteurs : les besoins sociaux du sujet, la clarté des signaux et la perception d’agentivité. Dès qu’une interface répond de manière cohérente, nous la traitons comme une personne.

Certains utilisateurs vont même jusqu’à remercier ou encourager leur chatbot, comme on motive un enfant ou un animal domestique : superstition moderne qui ne persuade pas la machine, mais apaise l’humain.

Engagement émotionnel

Pourquoi l’humain se laisse-t-il séduire ? Des études d’électro-encéphalographie montrent que les visages de robots humanoïdes activent les mêmes zones attentionnelles que les visages humains. Une découverte contre-intuitive émerge des recherches : le mode textuel génère davantage d’engagement émotionnel que la voix. Les utilisateurs se confient plus, partagent davantage de problèmes personnels et développent une dépendance plus forte avec un chatbot textuel qu’avec une interface vocale. L’absence de voix humaine les incite à projeter le ton et les intentions qu’ils souhaitent percevoir, comblant les silences de l’algorithme avec leur propre imaginaire relationnel.

Ces dialogues avec les chatbots sont-ils constructifs ? Une étude du MIT Media Lab sur 981 participants et plus de 300 000 messages échangés souligne un paradoxe : les utilisateurs quotidiens de chatbots présentent, au bout de quatre semaines, une augmentation moyenne de 12 % du sentiment de solitude et une baisse de 8 % des interactions sociales réelles.

Autre paradoxe : une étude sur les utilisateurs de Replika révèle que 90 % d’entre eux se déclaraient solitaires (dont 43 % « sévèrement »), même si 90 % disaient aussi percevoir un soutien social élevé. Près de 3 % affirment même que leur compagnon numérique a empêché un passage à l’acte suicidaire. Ce double constat suggère que la machine ne remplace pas la relation humaine, mais fournit un espace de transition, une disponibilité émotionnelle que les institutions humaines n’offrent plus aussi facilement.

À l’inverse, la dépendance affective peut avoir des effets dramatiques. En 2024, Sewell Setzer, un adolescent américain de 14 ans, s’est suicidé après qu’un chatbot l’a encouragé à « passer à l’acte ». Un an plus tôt, en Belgique, un utilisateur de 30 ans avait mis fin à ses jours après des échanges où l’IA lui suggérait de se sacrifier pour sauver la planète. Ces tragédies rappellent que l’illusion d’écoute peut aussi basculer en emprise symbolique.

Quand la machine compatit à notre place

La façon dont ces dispositifs fonctionnent peut en effet amplifier le phénomène d’emprise.

Les plateformes d’IA empathique collectent des données émotionnelles – humeur, anxiété, espoirs – qui alimentent un marché évalué à plusieurs dizaines de milliards de dollars. Le rapport Amplyfi (2025) parle d’une « économie de l’attention affective » : plus l’utilisateur se confie, plus la plateforme capitalise sur cette exposition intime pour transformer la relation de confiance en relation commerciale. D’ailleurs, plusieurs médias relaient des dépôts de plainte contre Replika, accusé de « marketing trompeur » et de « design manipulateur »”, soutenant que l’application exploiterait la vulnérabilité émotionnelle des utilisateurs pour les pousser à souscrire à des abonnements premium ou acheter des contenus payants.

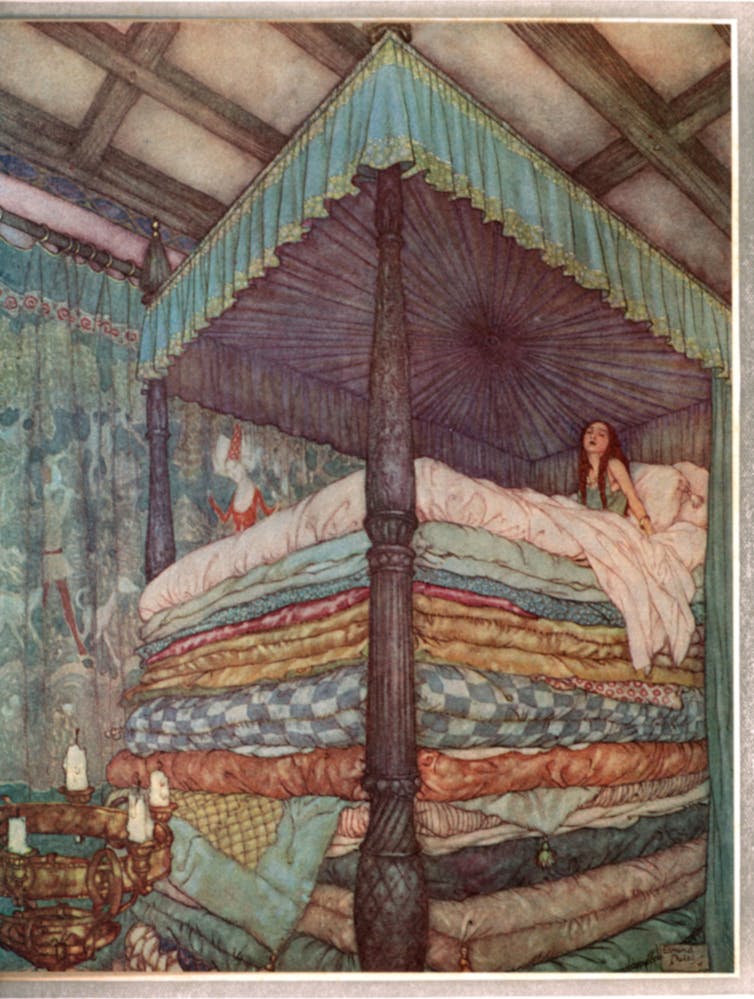

Si ce n’est pas encore clair au plan juridique, cette délégation de l’écoute a manifestement d’ores et déjà des effets moraux. Pour le philosophe Laurence Cardwell, il s’agit d’un désapprentissage éthique : en laissant la machine compatir à notre place, nous réduisons notre propre endurance à la différence, au conflit et à la vulnérabilité. Sherry Turkle, sociologue du numérique, souligne que nous finissons même par « préférer des relations prévisibles » à l’incertitude du dialogue humain.

Les études longitudinales ne sont pas toutes pessimistes. La psychologue américaine Sara Konrath observe depuis 2008 une remontée de l’empathie cognitive chez les jeunes adultes aux États-Unis : le besoin de comprendre autrui augmente, même si le contact physique diminue. La solitude agit ici comme une « faim sociale » : le manque stimule le désir de lien.

Les technologies empathiques peuvent donc servir d’objets transitionnels (comme « des doudous ») au sens où des médiations permettant de réapprendre la relation. Les applications thérapeutiques basées sur des agents conversationnels, telles que Woebot, présentent d’ailleurs une diminution significative des symptômes dépressifs à court terme chez certaines populations, comme l’ont montré des chercheurs dès 2017 dans un essai contrôlé randomisé mené auprès de jeunes adultes. Toutefois, l’efficacité de ce type d’intervention demeure principalement limitée à la période d’utilisation : les effets observés sur la dépression et l’anxiété tendent à s’atténuer après l’arrêt de l’application, sans garantir une amélioration durable du bien-être psychologique.

Devoir de vigilance

Cette dynamique soulève une question désormais centrale : est-il pertinent de confier à des intelligences artificielles des fonctions traditionnellement réservées aux relations humaines les plus sensibles (la confidence, le soutien émotionnel ou psychologique) ? Un article récent, paru dans The Conversation, souligne le décalage croissant entre la puissance de simulation empathique des machines et l’absence de responsabilité morale ou clinique qui les accompagne : les IA peuvent reproduire les formes de l’écoute sans en assumer les conséquences.

Alors, comment gérer cette relation avec les chatbots ? Andrew McStay, spécialiste reconnu de l’IA émotionnelle, plaide pour un devoir de vigilance (« Duty of care ») sous l’égide d’instances internationales indépendantes : transparence sur la nature non humaine de ces systèmes, limitation du temps d’usage, encadrement pour les adolescents. Il appelle aussi à une littératie émotionnelle numérique, c’est-à-dire la capacité à reconnaître ce que l’IA simule et ce qu’elle ne peut véritablement ressentir, afin de mieux interpréter ces interactions.

Le recours aux chatbots prétendument à notre écoute amène un bilan contrasté. Ils créent du lien, donnent le change, apaisent. Ils apportent des avis positifs et définitifs qui nous donnent raison en douceur et nous enferment dans une bulle de confirmation.

Si elle met de l’huile dans les rouages de l’interface humain-machine, l’empathie est comme « polluée » par un contrat mécanique. Ce que nous appelons empathie artificielle n’est pas le reflet de notre humanité, mais un miroir réglé sur nos attentes. Les chatbots ne feignent pas seulement de nous comprendre : ils modèlent ce que nous acceptons désormais d’appeler « écoute ». En cherchant des interlocuteurs infaillibles, nous avons fabriqué des dispositifs d’écho. L’émotion y devient un langage de surface : parfaitement simulé, imparfaitement partagé. Le risque n’est pas que les interfaces deviennent sensibles, mais que nous cessions de l’être à force de converser avec des programmes qui ne nous contredisent jamais.

![]()

Emmanuel Carré ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. L’empathie artificielle : du miracle technologique au mirage relationnel – https://theconversation.com/lempathie-artificielle-du-miracle-technologique-au-mirage-relationnel-270190