Source: The Conversation – UK – By Sara Fregonese, Associate Professor of political geography, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, University of Birmingham

The mass shooting during Hanukkah in Bondi Beach is a horrific reminder that contemporary terrorism can affect the places where we meet others, shop, celebrate and conduct our daily lives. However, our research suggests that what the UK public fears and assumes about terrorism threats is quite different from reality.

In 2022, we asked 5,000 people in the UK about their experiences and perceptions of terror threat and counter-terrorism measures.

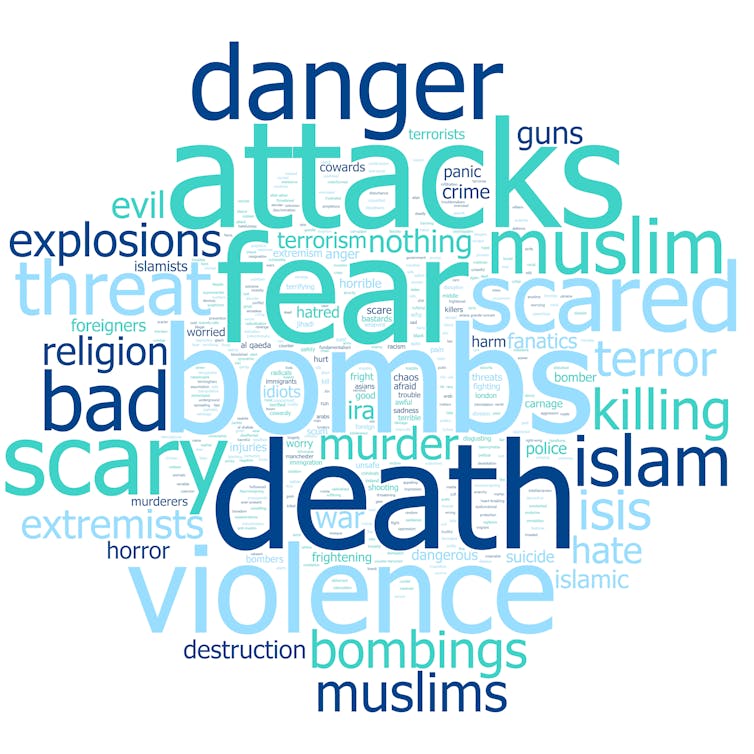

Respondents told us the first word that came to mind when they heard the word terrorism. Most prominent in their responses are references to bombs and bombings. This isn’t surprising, given the global prominence of such terrorist tactics for some time. However, evidence shows that nearly “80% of UK domestic terrorist attacks since 2018 have been carried out with bladed or blunt force weapons”.

In recent years, a global shift in terror tactics has made explosive attacks less common. Less sophisticated means of attacks – such as arson and the use of bladed weapons and firearms – have become more appealing financially and logistically, especially among lone actors.

In western Europe, terrorism is increasingly perpetrated via “low-tech attacks against public spaces carried out with everyday items”. This includes attacks using vehicles as weapons, which has led to a recent increase in hostile vehicle protective infrastructure in cities.

Sara Fregonese and Paul Simpson, CC BY

The UK public isn’t neurotically expecting explosions and deadly attacks, however. Only 8% of our respondents saw terrorism as the most important problem facing the UK, ranked behind poverty, health, the environment, and unemployment / job security. It is also seen as more significant than racism / discrimination, delinquency, and road safety.

It is important that the public knows what the nature of that problem is, especially considering the National Terrorism Threat Level has remained either severe or substantial for the past several years meaning an attack is likely.

Diverse perceptions

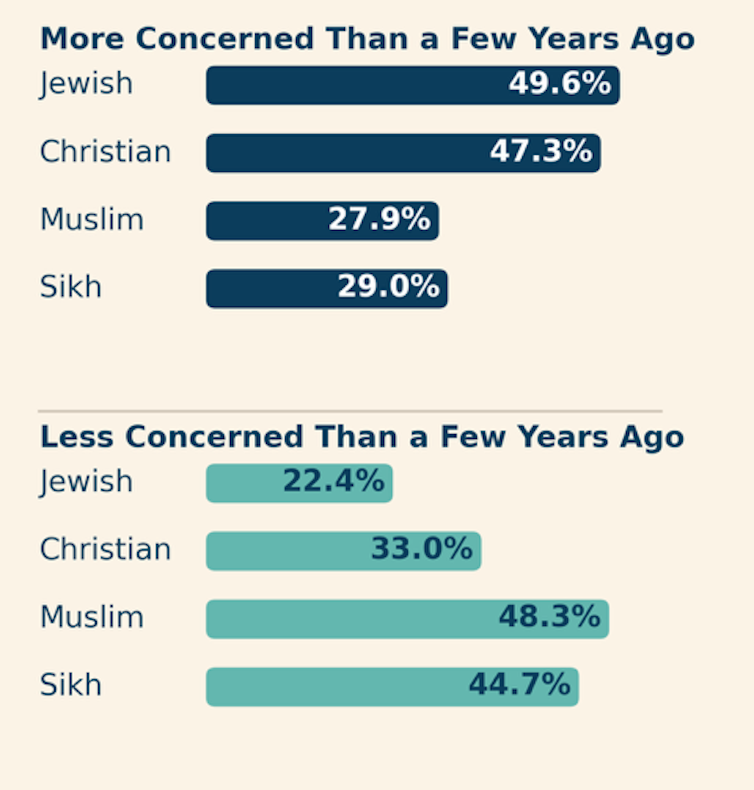

We also asked respondents how they felt about the threat of terrorism compared with a few years previously. Similar numbers felt more concerned about terrorism threats than in previous years (39.83%), as those feeling less concerned (35.65%). However, when breaking data down by religious belonging, a more complex picture emerged.

We saw diametrically opposed feelings of concern among Christians and Jewish respondents on the one hand, and Muslims and Sikhs on the other. In 2022, 49.6% of Jewish respondents declared themselves more concerned about terrorism threats than a few years earlier. Importantly, this preceded the Manchester Synagogue attack in November 2025 and the Bondi Beach attack.

Similarly, 47.3% of Christian respondents felt more concerned about terrorist threats than in previous years. Just 27.9% of Muslim respondents and 29% of Sikh respondents said they felt more concerned about terrorism threats than a few years earlier.

Muslim (48.3%) and Sikh (44.7%) respondents largely felt less concerned about terrorism in 2022 compared to a few years earlier. A lower proportion of Jewish (22.4%) and Christian (33%) respondents felt less concerned about terrorism in 2022.

Changing concern about terror threat by religious belief (2022)

Sara Fregonese and Paul Simpson, CC BY

We need to better understand how these perceptions and differences in concerns have formed. They may be connected to societal polarisation, and with different approaches and reactions to counter-terrorism measures.

Responding to terrorism

These findings matter for how governments respond to, and prepare the public for, terror threats.

UK government counter-terrorism policy has recently come under scrutiny. A report by the independent commission for counter-terrorism law, published in November 2025, called for substantial changes to the current system. This included recommendations for a narrower definition of terrorism and an overhaul of the Prevent Duty, which requires public bodies to identify and report signs of radicalisation.

The government’s national security strategy has also been criticised by the UK Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation for not taking online terror threats seriously enough.

One of the ways that governments respond to terror threats is through information campaigns intended to alert and educate the public on the current nature of threat. And yet, our data shows that public awareness of such campaigns is worryingly low – 83.5% of respondents aren’t aware of them at all. That rate declines further for those aged 50 and over.

Those who said they are aware of counter-terrorism information campaigns largely failed to recall what these campaigns actually are. Their answers gave incomplete, wrong or conflated campaign names and slogans.

One might wonder if multiple campaigns – Run, Hide, Tell (2015-onwards); See it, Say it, Sorted (2016-onwards); Action Counters Terrorism (2017-onwards) – have actually produced confusion rather than clarity among the public over the nature of terror threat and what to watch out for. Equally, they may have become such a ubiquitous background in our cities, that people are now paying little attention.

It is essential to address these misalignments between public understanding of terrorism and the current evidence. The public needs clear, easy to remember, and updated information about current threats. Without this, people will struggle to recognise current threats and attune their instincts on how to react to them correctly.

And, while the messaging needs to be coherent, attention needs to be paid to the evident diversity of experiences and views about threat and security measures. Given our findings on how different demographic groups perceive terrorism, the recent call for equality impact assessments of counter-terrorism measures is a timely one indeed.

![]()

Sara Fregonese received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/V01353X/1) which supported the research reported here

Paul Simpson received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/V01353X/1) which supported the research reported here

– ref. Why public views of terrorism don’t match the evidence, and what the government needs to do to keep people safe – https://theconversation.com/why-public-views-of-terrorism-dont-match-the-evidence-and-what-the-government-needs-to-do-to-keep-people-safe-272101