Source: The Conversation – UK – By Alice Vernon, Lecturer in Creative Writing and 19th-Century Literature, Aberystwyth University

This year’s BBC Ghost Story for Christmas is an adaptation of E. F. Benson’s 1912 tale of vampiric horror and haunted sleep, The Room in the Tower.

The unnamed narrator begins the story by relating a recurring nightmare he has suffered for 15 years. In the dream, he has been invited to the mansion of the Stone family. The dream begins pleasantly, with card games, cigarettes and light conversation. But it always takes a turn when the family’s fearsome matriarch, Mrs Stone, tells the narrator that he’ll now be shown to his room for the night – the titular room in the tower. Upon entering the room, he is overwhelmed with abject horror, and wakes up before he sees the object of his fear.

While visiting a friend one stormy summer’s day, the narrator finds himself at the very home he saw at least once a month in his dreams. Sure enough, he’s led to the room in the tower, where he finds a hideous portrait of the demonic Mrs Stone. The portrait is removed from the room at his request, but leaves curious bloodstains on the narrator and his friend’s hands. During the night, however, the narrator’s sleep is once again disturbed by the nightmare made manifest.

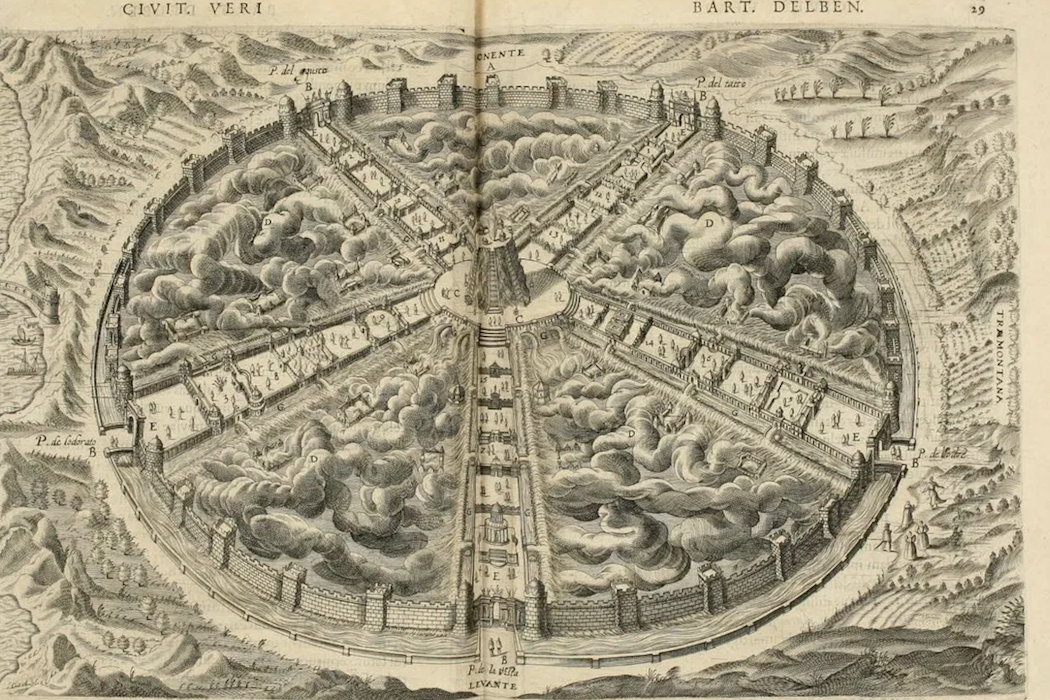

The New York Public Library

Many ghost stories take place in bedrooms. One of the BBC’s first ghost stories adapted for television was M. R. James’ Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad, which features a bumbling academic terrorised in his hotel room by a ghost quite literally wearing a bed sheet. Horror comes from a twisted reversal of what we expect to see and experience, and since the bed should be the place of utmost safety, it is ripe to be distorted into a place of existential dread.

Sleep, too, is a state of pure vulnerability. Those few breathless seconds after waking from a nightmare remind us just how defenceless we are. No tale of the supernatural from the early 20th century examines the way our troubled sleep can haunt us quite like The Room in the Tower.

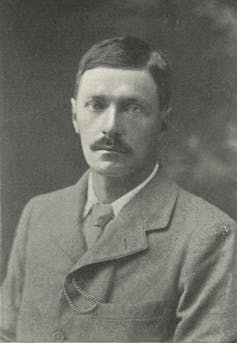

Benson grew up with ghosts. His father, Edward Benson, was the archbishop of Canterbury. He was good friends with novelist Henry James, and allegedly told his son a spooky story he’d heard that James later turned into The Turn of the Screw (1898).

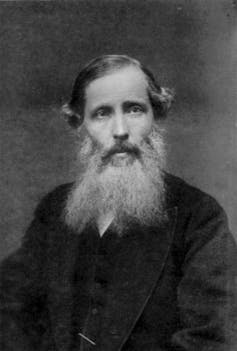

Benson’s mother was Mary Sidgwick, whose brother Henry was a founding member and first president of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). The SPR’s aim was to investigate strange and paranormal phenomena, with particular interests in thought transference (or telepathy), visions and hallucinations, and ghosts and hauntings.

Begun in 1882, the SPR almost immediately set about collecting a massive amount of data under their Census of Hallucinations. They sent out a questionnaire to the public, and received thousands of responses over several years, some with fascinating anecdotes about being terrorised by ghosts and monsters in the middle of the night. The SPR compiled these in an issue of their periodical in 1894.

WikiCommons

To read them in light of The Room of the Tower, it seems that Benson, too, knew what it feels like to be haunted by hallucinatory sleep disorders. Indeed, perhaps he even took direct influence from some of the anecdotes. The narrator in The Room in the Tower, being visited by a vampiric monster at the end of the story, describes himself as being “paralysed” – a typical sensation of sleep paralysis, which is often accompanied by a terrifying hallucination.

In Benson’s story, the narrator sees a “figure that leaned over the end of my bed”. In the SPR’s Census, a respondent referred to as Miss H. T. describes a horrifying visitation similar to the experience of Benson’s narrator. She wrote that she had seen the same figure three times, just as the narrator has the same nightmare over and over again. It would happen the same way every time; she would believe herself to be awake, and she would see a shimmer in the air that gradually solidified. Paralysed, she couldn’t move or scream to defend herself as the shape “took the form of mist and then developed into a dark veiled figure, which came nearer to me” and bent over the bed. Finally, the paralysis would lift, and the figure disappeared just as Miss H. T. threw her hands out towards it.

What both the Census and The Room in the Tower show is that ghosts don’t need to come from graveyards, gothic houses, or local legends. Often the most terrifying encounters, the experiences that prove most fruitful for ghost stories, are those our sleeping minds conjure up on the ethereal boundary between dreaming and waking.

The Room in the Tower will air on BBC One on Christmas Eve at 10pm, and will star Joanna Lumley as the terrifying Mrs Stone. For those of us prone to experience troubled sleep, it may well summon a nightmare of our own.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

![]()

Alice Vernon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The Room in the Tower: the ‘real’ hautings that inspired this year’s BBC Ghost Story for Christmas adaptation – https://theconversation.com/the-room-in-the-tower-the-real-hautings-that-inspired-this-years-bbc-ghost-story-for-christmas-adaptation-272309