Source: The Conversation – UK – By Paul Hanel, Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology, University of Essex

Talk to a random member of the public and they’re likely to say that people’s behaviour is getting worse. From brazen shoplifting, to listening to music out loud on public transport, to violence against retail workers, there are plenty of reasons we might feel bleak about other people.

This perception is backed up by research: a study published in June 2023 found that people in over 60 countries believe that basic decency is declining. A 2025 poll of 9,600 Americans found that 46% believed that rudeness is overall increasing, whereas only 9% found it was decreasing compared to pre-pandemic levels.

But people’s perception can be inaccurate. In my research, I investigate how accurate people’s perceptions about other people are, the implications of inaccurate perceptions, and what happens when those misperceptions are corrected.

And it’s clear that there are some misperceptions at play here. If we look at people’s values, those abstract ideals that guide our behaviour, there are reasons to be positive about society.

In a 2022 study of 32,000 people across 49 cultural groups, the values of loyalty, honesty and helpfulness ranked highest, while power and wealth ranked lowest. The results offer little support for claims of moral decline. An interactive tool, developed by social scientist Maksim Rudnev using data from the European Social Survey, shows that the pattern remained consistent between 2002-23 across over 30 European countries.

Further studies show people’s values are broadly similar across over 60 countries, education levels, religious denominations and gender (there are exceptions of course). That is, there is substantial overlap between the responses between both groups.

Even the values of 2,500 Democrats or Republicans in the USA in 2021-23, or of 1,500 Leave and Remain voters of the Brexit referendum in 2016-17, are remarkably similar. This suggests an alternate narrative to perceptions of countries being divided and polarised.

One limitation of these findings is that they are based on people’s self-reports. This means these results can be inaccurate, for example because people wanted to portray themselves positively. But what about people’s actual behaviour?

Good citizens

Quite a few studies suggest that most people are actually behaving morally. For example, when researchers analysed actual public conflicts recorded by CCTV, they found that in nine out of ten conflicts a bystander intervened (in cases where bystanders were present). These findings, from 2020, were similar across the Netherlands, South Africa and the UK.

People intervene in knife or terrorist attacks, even when they put themselves in danger. While these cases are rare, they demonstrate that many people are willing to help even under extreme circumstances.

In less dramatic situations we can also observe that people are considerate of others. For example, a 2019 study found that in 38 out of 40 countries investigated lost wallets were, on average, more likely to be returned if they contained a bit of cash rather than no cash, and even more likely to be returned when they contained a fair bit of cash. This is likely because finders recognised that the loss would be more harmful to the owner of the wallet.

In another experiment (2023), 200 people from seven countries were given US$10,000 (£7,500) with almost no strings attached. Participants spent over $4,700 on other people and donated $1,700 to charity.

But what about changes over time? It might be that people 50 or 100 years ago behaved more morally. There are not many studies that systematically track behaviour change over time, but one study found that Americans became slightly more cooperative between the 1950s and the 2010s when interacting with strangers.

Why misperceptions persist

Why do quite a few people still believe that society is in moral decline? For one thing, news outlets tend to focus on negative events. Negative news is also more likely to be shared on social media. For example, numerous studies noticed that when disasters strike (hurricanes, earthquakes), many media stations report panic and cruelty, even though people usually cooperate with and support each other.

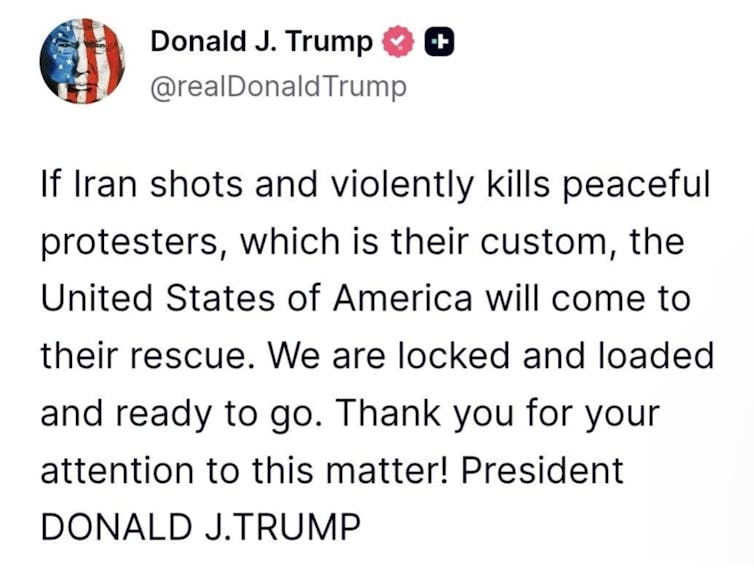

In addition, people who hold more extreme political views – on either the left or the right – are more likely to post online, as are bots from Russia and elsewhere. In other words, what we see on social media is by no means representative of the population.

Of course, none of this denies that a minority of people can cause serious harm, or that some aspects of public life, such as online abuse of children, may be worsening. Further, these trends do not necessarily reflect how the average person behaves or what they value.

Dmytro Zinkevych/Shutterstock

It matters if people are overly pessimistic about others. People who wrongly believe that others care more about selfish values and less about compassionate ones are, on average, less likely to volunteer or vote. This is not surprising: why invest your time in people you think would never return the favour?

Numerous experiments have found that showing people that others share, on average, similar values and beliefs to their own, can make them more trusting and hopeful for the future. Talking to others, be it friends, people you only know loosely or strangers, can make us realise that other people are mostly friendly, and it can also make us feel better.

Volunteering, joining local groups or attending neighbourhood events can be a good idea: helping others makes us feel better. Finally, reading positive news stories or focusing on other people’s kindness can also help our outlook.

In a nutshell, the evidence suggests that moral decline is not happening, even if there are examples of some bad behaviour on the rise. If we all were to stop talking to other people assuming they would mean us harm, cease to go the extra mile for other people and so on, there is a risk we all become more self-centred and decline would eventually happen. Luckily, we, as a society, can influence our own fate.

![]()

Paul Hanel received in the past funding from the Economic and Social Research Council as well as Research England.

– ref. Think society is in decline? Research gives us some reasons to be cheerful – https://theconversation.com/think-society-is-in-decline-research-gives-us-some-reasons-to-be-cheerful-268834