Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Tulio Alberto Álvarez-Ramos, Profesor/Investigador Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Jefe de Cátedra de Derecho Constitucional de la Universidad Central de Venezuela, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello

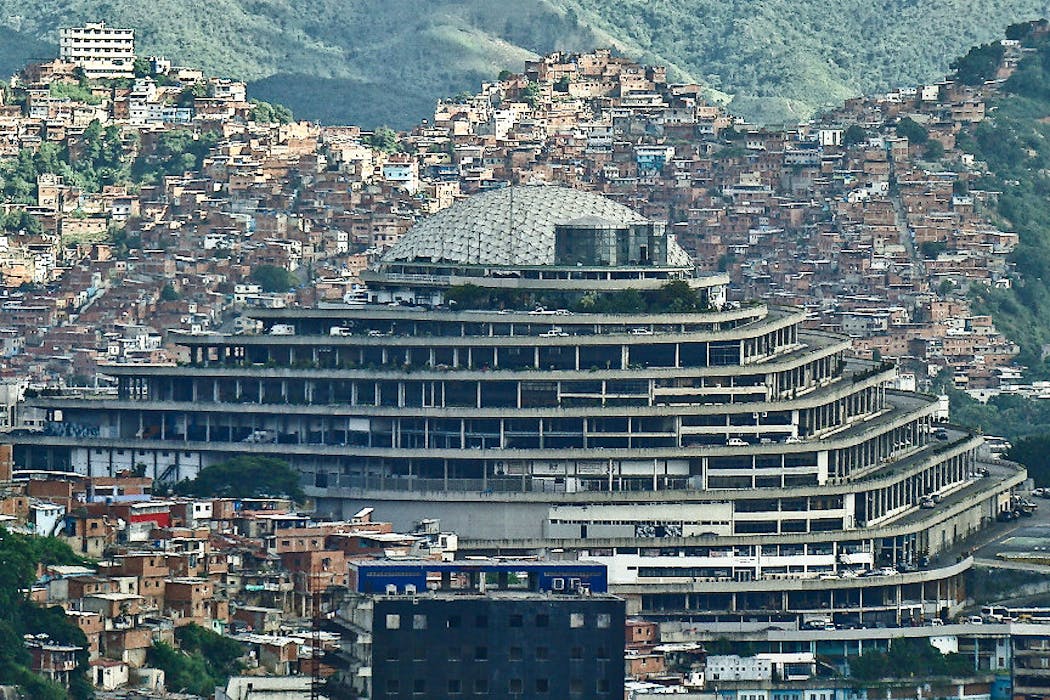

Mi esposa me pidió algo que parecía sencillo: acercarla al Helicoide para tomar unas fotografías. Artista plástica, suele recorrer Caracas buscando en cada edificio las huellas de la ciudad que fuimos y la que aún disfrutamos. En las visitas, sus grupos de amigos celebran la diversidad de estilos, la modernidad truncada y las cicatrices arquitectónicas que marcan nuestro paisaje.

El Helicoide, levantado en tiempos de la dictadura de Marcos Pérez Jiménez e hibernado en las administraciones democráticas posteriores, fue concebido como un manifiesto del brutalismo: hormigón desnudo, monumentalidad sin ornamentos, funcionalidad que pretendía simbolizar progreso.

Mercedes me recordó que esa estética buscaba revelar la expresividad de los materiales, la honestidad del hormigón. Pero en Caracas, esa sinceridad se volvió metáfora de otra brutalidad: la del poder que encierra y castiga.

Esta vez, el paseo dominical no me fue grato. Durante años lo visité para acompañar a amigos condenados por haber defendido la vida en aquella célebre jornada cívica del 11 de abril de 2022. Hasta que un día normal de visita, la amenaza se hizo explícita: “Si entra, no sale; si regresa, se queda aquí”. El Helicoide se convirtió así en un fantasma personal, un recordatorio de cómo el hormigón puede ser cómplice del terror.

Sin dignidad y sin Dios

El ejercicio del poder revela siempre una tensión entre el bien y el mal. Su peor rostro se muestra en la violencia y humillación de quienes padecen persecución por causa de la justicia. La tortura, física y mental, constituye uno de los crímenes más horrendos, pues destruye cuerpos y también almas.

El Helicoide se inscribe en una genealogía de lugares donde la brutalidad se institucionalizó: la ESMA en Argentina, convertida hoy en espacio de memoria; los centros de detención en Cuba; Tadmur, conocido como “el reino de la muerte y la locura”, en Siria; Bagram en Afganistán, donde prisioneros fueron encadenados y golpeados hasta la muerte; y los centros clandestinos de la Stasi en Alemania Oriental. Todos comparten una misma lógica: el poder que se cree absoluto y convierte al ser humano en objeto de sufrimiento.

Orden de cierre, pero no de olvido

El anuncio de Delcy Rodríguez, el 30 de enero de 2026, sobre el cierre del Helicoide y otros centros de detención, fue presentado como un gesto de apertura y reconversión hacia espacios comunitarios. Sin embargo, la memoria no se borra con decretos. El Helicoide no es solo un edificio: es un símbolo de represión documentado en informes internacionales que lo señalan como escenario de tortura y violaciones sistemáticas de derechos humanos.

En 2019, la Alta Comisionada Michelle Bachelet, tras su visita a Venezuela, incluyó al Helicoide en su informe como centro de detención del Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional (SEBIN). Allí se denunciaron torturas, tratos crueles e inhumanos, falta de acceso a abogados y condiciones degradantes para los presos políticos. Un año después, la Misión Internacional de Determinación de los Hechos del Consejo de Derechos Humanos de la ONU identificó al Helicoide como uno de los principales centros de tortura en el país, junto con la sede de la Dirección General de Contrainteligencia Militar (DGCIM). El informe detalló prácticas sistemáticas como descargas eléctricas, asfixia, violencia sexual y aislamiento prolongado, calificándolas como crímenes de lesa humanidad (ONU, 2020).

Los informes posteriores (2021–2024) confirmaron que el Helicoide seguía siendo utilizado para detenciones arbitrarias y torturas. Testimonios lo describieron como un “laberinto de miedo” y lo señalaron como “símbolo de la represión institucionalizada”. La arquitectura brutalista que alguna vez pretendió representar modernidad se convirtió en arquitectura del dolor, un espacio donde la dignidad humana fue sistemáticamente negada.

La Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos también ha denunciado al Helicoide. En 2025 solicitó una visita para verificar las condiciones de los detenidos, subrayando las denuncias de tortura y hacinamiento. Ese mismo año, en un comunicado reiteró su competencia sobre Venezuela y describió al Helicoide como “símbolo del horror”. La Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, en una sentencia de agosto de 2025, reafirmó su jurisdicción sobre el país y vinculó su supervisión con centros como el que nos ocupa.

Existe plena coincidencia de los órganos internacionales en materia de derechos humanos: el Helicoide es un escenario de crímenes contra la humanidad. Su cierre administrativo no borra las huellas del dolor ni las responsabilidades históricas que allí se gestaron.

Presentado en el MoMA de Nueva York

El Helicoide, que en 1961 alcanzó protagonismo internacional al ser presentado en el debate arquitectónico del MoMA de Nueva York, fue concebido como símbolo de modernidad y progreso bajo el signo del brutalismo. Hoy, sin embargo, carga con una triste fama: emblema de brutalidad, represión y tortura. Esta paradoja no es ajena a la historia urbana latinoamericana: Venezuela, como tantos países de la región, heredó los sueños de civilización y modernidad, pero los distorsionó bajo dictaduras, populismos y regímenes autoritarios.

El Helicoide encarna esa contradicción: una obra monumental que debía ser centro comercial futurista, convertida en cárcel de cuerpos y esperanzas. La arquitectura, pensada como motor de desarrollo, se transformó en escenario de indignidad e impunidad.

Hoy, lo que representó un desafío arquitectónico constituye un reto para instaurar en nuestro país la Justicia y restaurar la dignidad humana como centro de toda acción política. Como proclamaron nuestros hermanos argentinos, después de superar la prueba y asumir el costo de los errores de su clase política. Nunca más.

![]()

Tulio Alberto Álvarez-Ramos no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. El Helicoide caraqueño: del brutalismo arquitectónico a la brutalidad – https://theconversation.com/el-helicoide-caraqueno-del-brutalismo-arquitectonico-a-la-brutalidad-274825