Source: The Conversation – USA – By Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti, Associate Research Scientist, University of Michigan

Weather forecasting is a powerful tool. During hurricane season, for instance, meteorologists create computer simulations to forecast how these destructive storms form and where they might travel, which helps prevent damage to coastal communities. When you’re trying to forecast space weather, rather than storms on Earth, creating these simulations gets a little more complex. To simulate space weather, you would need to fit the Sun, the planets and the vast empty space between them in a virtual environment, also known as a simulation box, where all the calculations would take place.

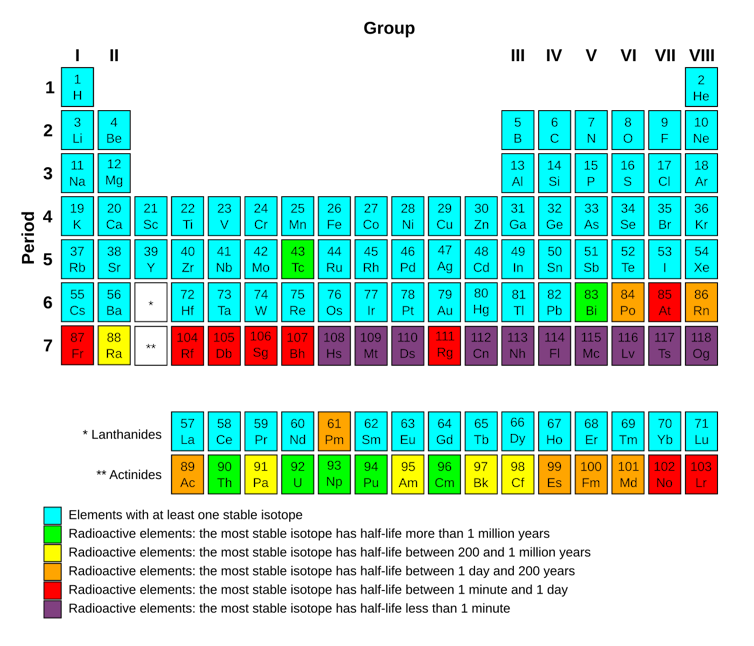

Space weather is very different from the storms you see on Earth. These events come from the Sun, which ejects eruptions of charged particles and magnetic fields from its surface. The most powerful of these events are called interplanetary coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, which travel at speeds approaching 1,800 miles per second (2,897 kilometers per second).

To put that in perspective, a single CME could move a mass of material equivalent to all the Great Lakes from New York City to Los Angeles in just under two seconds – almost faster than it takes to say “space weather.”

When these CMEs hit Earth, they can cause geomagnetic storms, which manifest in the sky as beautiful auroras. These storms can also damage key technological infrastructure, such as by interfering with the flow of electricity in the power grid and causing transformers to overheat and fail.

Frank Olsen, Norway/Moment via Getty Images

To better understand how these storms can wreak so much havoc, our research team created simulations to show how storms interact with Earth’s natural magnetic shield and trigger the dangerous geomagnetic activity that can shut down electric grids.

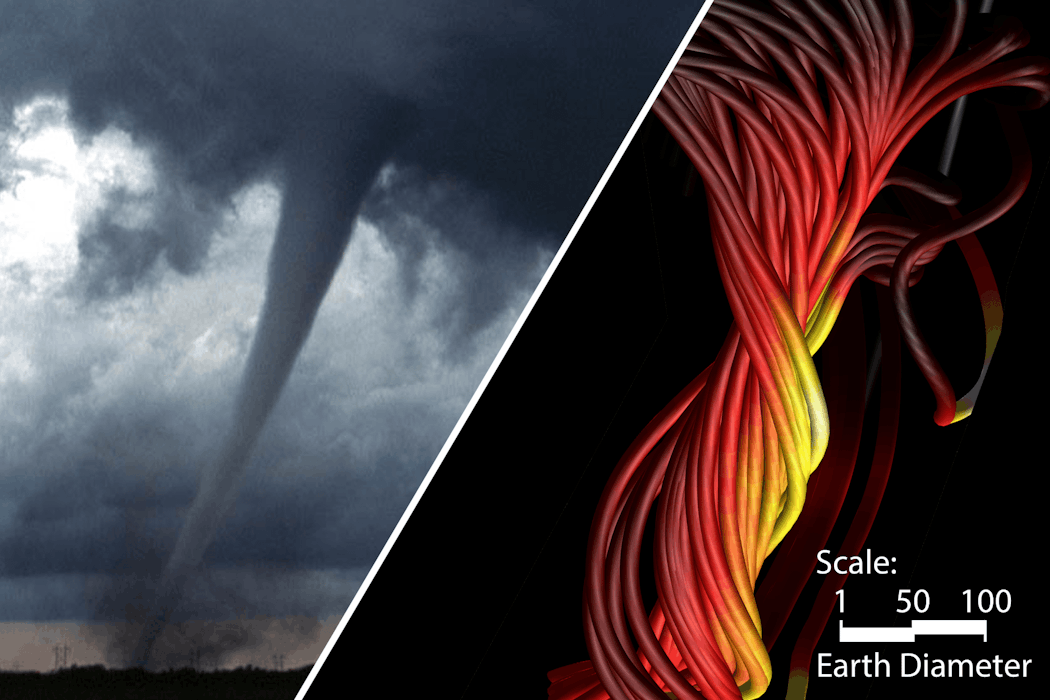

In a study published in October 2025 in the Astrophysical Journal, we modeled one of the sources of these geomagnetic storms: small, tornado-like vortices spun off of an ejection from the Sun. These vortices are called flux ropes, and satellites had previously observed small flux ropes – but our work helped uncover how they are generated.

The challenge

Our team started this research in summer 2023, when one of us, a space weather expert, spotted inconsistencies in space weather observations. This work had found geomagnetic storms occurring during periods when no solar eruptions were predicted to hit Earth.

Bewildered, the space weather expert wanted to know if there could be space weather events that were smaller than coronal mass ejections and did not originate directly from solar eruptions. He predicted that such events might form in the space between the Sun and Earth, instead of in the Sun’s atmosphere.

One example of such smaller space weather events is a magnetic flux rope – bundles of magnetic fields wrapped around each other like a rope. Its detection in computer simulations of solar eruptions would hint to where these space weather events may be forming. Unlike satellite observations, in simulations you can turn back the clock or track an event upstream to see where they originate.

So he asked the other author, a leading simulation expert. It turned out that finding smaller space weather events was not as simple as simulating a big solar eruption and letting the computer model run long enough for the eruption to reach Earth. Current computer simulations are not meant to resolve these smaller events. Instead, they are designed to focus on the large solar eruptions because these have the most effects on infrastructure on Earth.

This shortfall was quite disappointing. It was like trying to forecast a hurricane with a simulation that only shows you global weather patterns. Because you can’t see a hurricane at that scale, you would completely miss it.

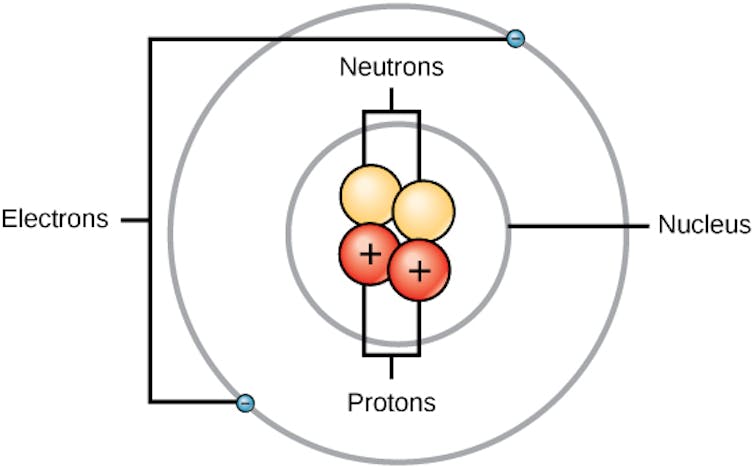

These larger-scale simulations are known as global simulations. They study how solar eruptions form on the Sun’s surface and travel through space. These simulations treat streams of charged particles and magnetic fields floating through space as fluids to reduce the computational cost, compared with modeling every charged particle independently. It’s like measuring the overall temperature of water in a bottle, instead of tracking every single water molecule individually.

Because these simulations are computational phenomena that happen across such a vast space, they can’t resolve every detail. To affordably resolve the vast space between the Sun and the planets, researchers divide the space into large cubes – analogous to two-dimensional pixels in a camera. In the simulation, these cubes each represent an area 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) wide, tall and across. That distance is equivalent to about 1% of the distance from Earth to the Sun.

The search begins

Our search began with what felt like hunting for a needle in a haystack. We were looking into old global simulations, searching for a tiny, transient blob – which would signify a flux rope – within an area of space hundreds of times wider than the Sun itself. Our initial search did not yield anything.

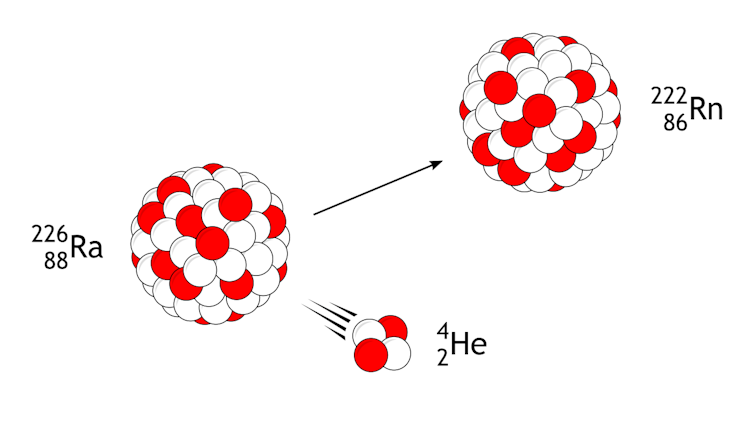

We then shifted our focus to the simulations of the May 2024 solar eruption event. This time, we specifically looked at the region where the solar eruption collided into a quiet flow of charged particles and magnetic fields, called the solar wind, ahead of it.

There it was: a distinct system of magnetic flux ropes.

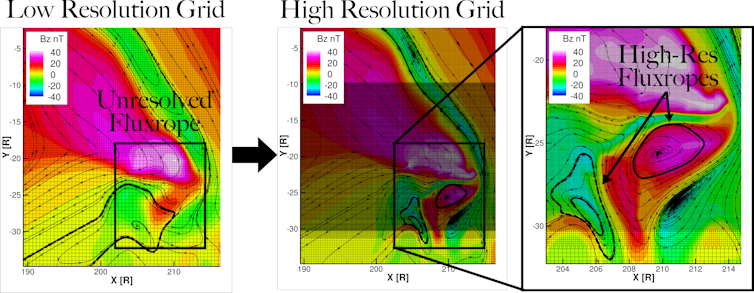

However, our excitement was short-lived. We could not tell where these flux ropes came from. The modeled flux ropes were also too small to survive, eventually fizzling out because they became too small to resolve with our simulation grid.

But that was the type of clue we needed – the presence of flux ropes at the location where the solar eruption collided with the solar wind.

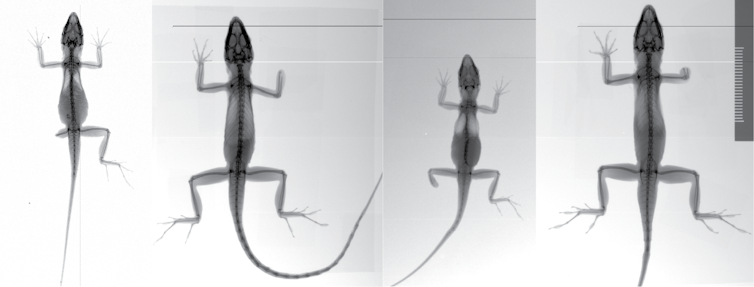

To settle the issue, we decided to bridge this gap and create a computer model with a finer grid size than those previous global simulations used. Since increasing the resolution across the entire simulation space would have been prohibitively expensive, we decided to only increase the simulation resolution along the trajectory of the flux ropes.

The new simulations could now resolve features that spanned distances six times Earth’s 8,000-mile (or 128,000-kilometer) diameter down to tens of thousands of miles – nearly 100 times better than previous simulations.

CC BY-NC-ND

Making the discovery

Once we designed and tested the simulation grid, it was time to simulate that same solar eruption that led to the formation of those flux ropes in the less fine-grained model. We wanted to study the formation of those flux ropes and how they grew, changed shape and possibly terminated in the narrow wedge encompassing the space between the Sun and Earth. The results were astonishing.

The high-resolution view revealed that the flux ropes formed when the solar eruption slammed into the slower solar wind ahead of it. The new structures possessed incredible complexity and strength that persisted far longer than we expected. In meteorological terms, it was like watching a hurricane spawn a cluster of tornadoes.

We found that the magnetic fields in these vortices were strong enough to trigger a significant geomagnetic storm and cause some real trouble here on Earth. But most importantly, the simulations confirmed that there are indeed space weather events that form locally in the space between the Sun and Earth. Our next step is to simulate how such tornado-like features in the solar wind may impact our planet and infrastructure.

Watching these flux ropes in the simulation form so quickly and move toward Earth was exciting, but concerning. It was exciting because this discovery could help us better plan for future extreme space weather events. It was at the same time concerning because these flux ropes would only appear as a small blip in today’s space weather monitors.

We would need multiple satellites to directly see these flux ropes in greater detail so that scientists can more reliably predict whether, when and in what orientation they may affect our planet and what the outcome may be. The good news is that scientists and engineers are developing the next-generation space missions that could address this.

![]()

Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti is the Principal Investigator of Space Weather Investigation Frontier (SWIFT). He receives funding from NASA.

W. Manchester is a Co-Investigator of Space Weather Investigation Frontier (SWIFT). He receives funding from NASA and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

– ref. ‘Space tornadoes’ could cause geomagnetic storms – but these phenomena, spun off ejections from the Sun, aren’t easy to study – https://theconversation.com/space-tornadoes-could-cause-geomagnetic-storms-but-these-phenomena-spun-off-ejections-from-the-sun-arent-easy-to-study-266567