Source: The Conversation – USA – By Christopher M. Filley, Professor Emeritus of Neurology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

On Oct. 25, 2023, a 40-year old man named Robert Card opened fire with a semi-automatic rifle at a bowling alley and nearby bar in Lewiston, Maine, killing 18 people and wounding 13 others. Card was found dead by suicide two days later. His autopsy revealed extensive damage to the white matter of his brain thought to be related to a traumatic brain injury, which some neurologists proposed may have played a role in his murderous actions.

Neurological evidence such as magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, is widely used in court to show whether and to what extent brain damage induced a person to commit a violent act. That type of evidence was introduced in 12% of all murder trials and 25% of death penalty trials between 2014 and 2024. But it’s often unclear how such evidence should be interpreted because there’s no agreement on what specific brain injuries could trigger behavioral shifts that might make someone more likely to commit crimes.

We are two behavioral neurologists and a philosopher of neuroscience who have been collaborating over the past six years to investigate whether damage to specific regions of the brain might be somehow contributing to people’s decision to commit seemingly random acts of violence – as Card did.

With new technologies that go beyond simply visualizing the brain to analyze how different brain regions are connected, neuroscientists can now examine specific brain regions involved in decision-making and how brain damage may predispose a person to criminal conduct. This work may in turn shed light on how exactly the brain plays a role in people’s capacity to make moral choices.

Linking brain and behavior

The observation that brain damage can cause changes to behavior stretches back hundreds of years. In the 1860s, the French physician Paul Broca was one of the first in the history of modern neurology to link a mental capacity to a specific brain region. Examining the autopsied brain of a man who had lost the ability to speak after a stroke, Broca found damage to an area roughly beneath the left temple.

Broca could study his patients’ brains only at autopsy. So he concluded that damage to this single area caused the patient’s speech loss – and therefore that this area governs people’s ability to produce speech. The idea that cognitive functions were localized to specific brain areas persisted for well over a century, but researchers today know the picture is more complicated.

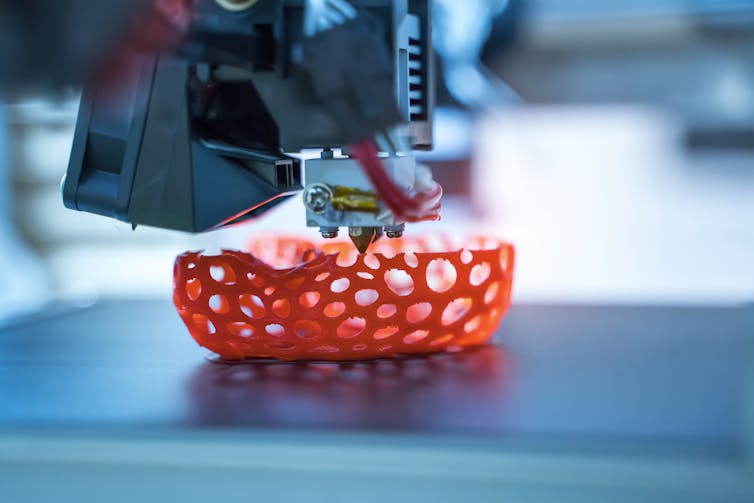

As brain imaging tools such as MRI have improved since the early 2000s it’s become increasingly possible to safely visualize people’s brains in stunning detail while they are alive. Meanwhile, other techniques for mapping connections between brain regions have helped reveal coordinated patterns of activity across a network of brain areas related to certain mental tasks.

With these tools, investigators can detect areas that have been damaged by brain disorders, such as strokes, and test whether that damage can be linked to specific changes in behavior. Then they can explore how that brain region interacts with others in the same network to get a more nuanced view of how the brain regulates those behaviors.

This approach can be applied to any behavior, including crime and immorality.

White matter and criminality

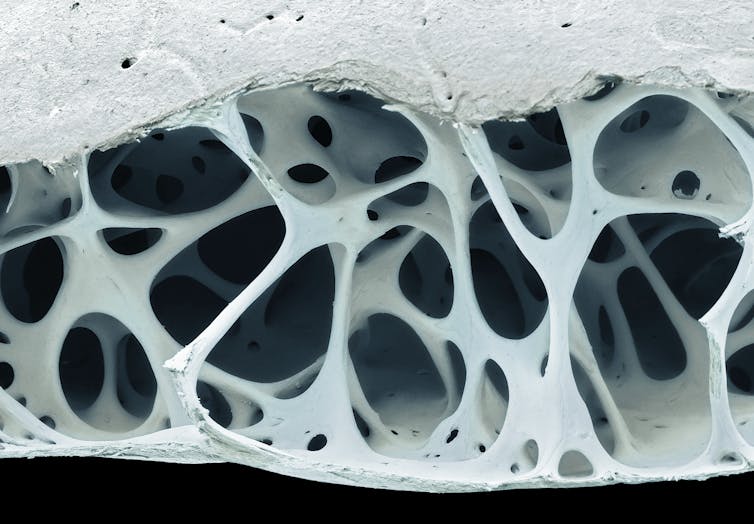

Complex human behaviors emerge from interacting networks that are made up of two types of brain tissue: gray matter and white matter.Gray matter consists of regions of nerve cell bodies and branching nerve fibers called dendrites, as well as points of connection between nerve cells. It’s in these areas that the brain’s heavy computational work is done. White matter, so named because of a pale, fatty substance called myelin that wraps the bundles of nerves, carries information between gray matter areas like highways in the brain.

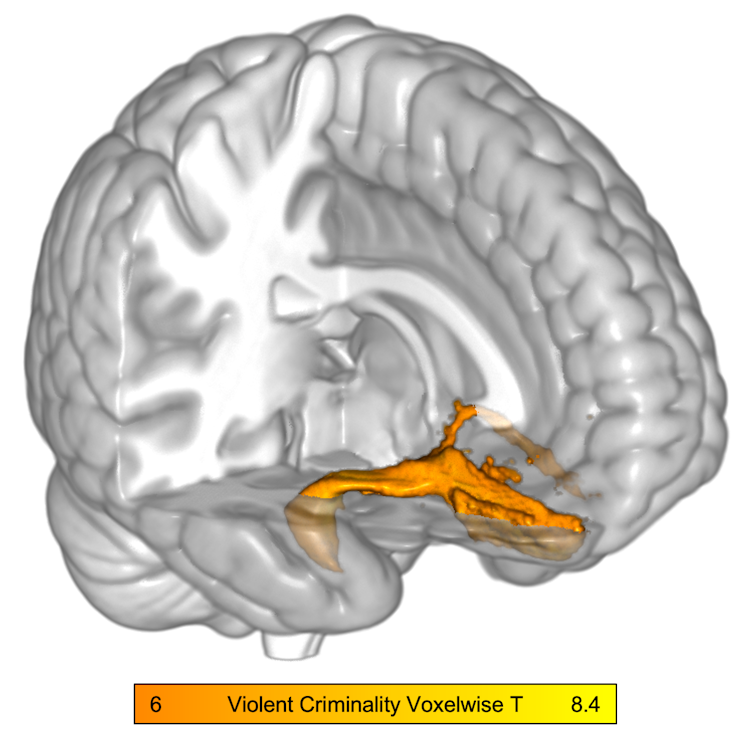

Brain imaging studies of criminality going back to 2009 have suggested that damage to a swath of white matter called the right uncinate fasciculus is somehow involved when people commit violent acts. This tract connects the right amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep in the brain involved in emotional processing, with the right orbitofrontal cortex, a region in the front of the brain involved in complex decision-making. However, it wasn’t clear from these studies whether damage to this tract caused people to commit crimes or was just a coincidence.

In a 2025 study, we analyzed 17 cases from the medical literature in which people with no criminal history committed crimes such as murder, assault and rape after experiencing brain damage from a stroke, tumor or traumatic brain injury. We first mapped the location of damage in their brains using an atlas of brain circuitry derived from people whose brains were uninjured. Then we compared imaging of the damage with brain imaging from more than 700 people who had not committed crimes but who had a brain injury causing a different symptom, such as memory loss or depression.

Isaiah Kletenik, CC BY-NC-ND

In the people who committed crimes, we found the brain region that popped up the most often was the right uncinate fasciculus. Our study aligns with past research in linking criminal behavior to this brain area, but the way we conducted it makes our findings more definitive: These people committed their crimes only after they sustained their brain injuries, which suggests that damage to the right uncinate fasciculus played a role in triggering their criminal behavior.

These findings have an intriguing connection to research on morality. Other studies have found a link between strokes that damaged the right uncinate fasciculus with loss of empathy, suggesting this tract somehow regulates emotions that affect moral conduct. Meanwhile, other work has shown that people with psychopathy, which often aligns with immoral behavior, have abnormalities in their amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex regions that are directly connected by the uncinate fasciculus.

Neuroscientists are now testing whether the right uncinate fasciculus may be synthesizing information within a network of brain regions dedicated to moral values.

Making sense of it all

As intriguing as these findings are, it is important to note that many people with damage to their right uncinate fasciculus do not commit violent crimes. Similarly, most people who commit crimes do not have damage to this tract. This means that even if damage to this area can contribute to criminality, it’s only one of many possible factors underlying it.

Still, knowing that neurological damage to a specific brain structure can increase a person’s risk of committing a violent crime can be helpful in various contexts. For example, it can help the legal system assess neurological evidence when judging criminal responsibility. Similarly, doctors may be able to use this knowledge to develop specific interventions for people with brain disorders or injuries.

More broadly, understanding the neurological roots of morality and moral decision-making provides a bridge between science and society, revealing constraints that define how and why people make choices.

![]()

Isaiah Kletenik receives funding from the NIH.

Nothing to disclose.

Christopher M. Filley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Certain brain injuries may be linked to violent crime – identifying them could help reveal how people make moral choices – https://theconversation.com/certain-brain-injuries-may-be-linked-to-violent-crime-identifying-them-could-help-reveal-how-people-make-moral-choices-262034