Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Emma Kennedy, Assistant Professor of Christian Ethics, Villanova University

Along the 2024 presidential campaign trail, Donald Trump pledged to make in vitro fertilization, or IVF, free – part of his party’s wider push for a new American “baby boom.”

But in October 2025, when the administration revealed its IVF proposal, many health care experts pointed out that it falls short of mandating insurance companies to cover the procedure.

Since Trump returned to the White House, it has become clear just how fraught IVF is for his base. Some conservative Christians oppose IVF because it often involves destroying extra embryos not implanted in the woman’s uterus.

According to Politico, anti-abortion groups lobbied against a requirement for employers to cover IVF. Instead, some vouched for “restorative reproductive medicine” – a term that has been around for decades but has received much more attention, especially from conservatives, in the past few months.

Proponents of restorative reproductive medicine tend to present it as an alternative to IVF: a different way of treating infertility, focused on treating underlying causes. But the approach is controversial, and some practitioners closely link their treatments to Catholic teachings.

As a scholar of religion, I study U.S. Catholics’ varied perspectives on infertility, seeking to understand how religious beliefs and practices influence physicians’ and patients’ choices. Their perspectives help provide a more nuanced understanding of Christianity’s role in the U.S. reproductive and political landscape.

Defining restorative reproductive medicine

Clinics that advertise themselves as offering restorative reproductive medicine try to diagnose underlying issues that could make conception difficult, like endometriosis. Typically, a patient and provider will closely monitor the patient’s menstrual cycle to identify potential abnormalities. Interventions include hormone therapies, medications, supplements, surgeries and lifestyle changes.

Iana Pronicheva/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Much of the approach resembles the initial testing used to evaluate patients in mainstream reproductive endocrinology and infertility clinics. However, restorative reproductive medicine clinics do not typically offer IVF or other assisted reproductive technologies.

Depending on who you ask, proponents are not necessarily opposed to IVF; they see their treatments as another option to explore. Some clinicians, however, closely link their treatment offerings to their religious commitments and opposition to abortion.

Restorative reproductive medicine has prompted criticism from professional medical organizations. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a statement in May 2025 calling it a “rebranding” of standard infertility treatment, with “ideologically driven restrictions that could limit patient care.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a brief warning that it is a “nonmedical approach” that threatens to impede access to IVF.

These critics are concerned that the focus on lifestyle changes and surgery may not address patients’ difficulties conceiving, while putting them through other unsuccessful treatments.

Church teachings

Today, restorative reproductive medicine is often described as gaining steam with conservative Christians and the “Make America Healthy Again,” or MAHA, movement. Its roots, though, are decades old, and largely Catholic.

Part of the Catholic Church’s objection to IVF stems from a concern that unused embryos are often discarded and destroyed. The church’s position is that all embryos ought to be treated with the same respect afforded a person – one of the key reasons its teachings oppose abortion.

Disapproval of IVF also stems from the church’s official teachings on marriage. According to this teaching, marriage has two chief ends, which it calls “procreation and union”: Typically, procreation is understood to mean having children, while union involves physical, emotional and spiritual intimacy. In this understanding, sexual intercourse should preserve what the church calls an “inseparable connection” between these two meanings.

The Catholic Church opposes artificial contraception because its goal is to block procreation. Instead, Catholics are encouraged to use “Natural Family Planning” – tracking a woman’s cycle so that couples can choose to abstain from sex during fertile periods. Similarly, it opposes artificial insemination and IVF because, by moving fertilization out of the body and into the lab, the process separates procreation from the act of sexual intercourse.

Survey data suggests most U.S. Catholics do not agree with these official stances, nor do they follow them.

Catholic doctors who do agree with official church teachings, however, have played a key role in developing infertility treatments that align with them. One of the most influential is Dr. Thomas W. Hilgers, who co-developed a “Natural Family Planning” method called the Creighton Model. In the early 1990s, he also developed NaProTechnology, an approach that seeks to identify fertility issues using cycle tracking, and then treat them with various medical and surgical interventions.

The NaProTechnology approach could be said to fall under the umbrella of restorative reproductive medicine, but it has mostly been used by Catholic reproductive health clinics and hospitals. Catholic physicians’ networks promote it, as do parishes and dioceses.

Navigating infertility

For Catholics who share the church’s official perspective on IVF, NaProTechnology and the clinics offering it are often a welcome alternative. Several of the Catholic women I interviewed as part of my academic research had also been to mainstream fertility clinics, but they felt that those providers did not offer much apart from IVF.

By contrast, the clinics offering NaProTechnology were often cheaper, in part because they do not offer IVF. They were also easier to navigate, since clinicians shared these patients’ religious views. Many felt that the providers were able to spend more time with them, helped them learn about their bodies, and were committed to understanding underlying issues beyond infertility.

However, others found clinics offering NaProTechnology to be lacking, often because clinicians weren’t up front about its limitations, especially when it comes to male infertility. Some patients felt that clinicians weren’t willing to admit drawbacks, for fear it would encourage couples to try IVF.

Catherine McQueen/Moment via Getty Images

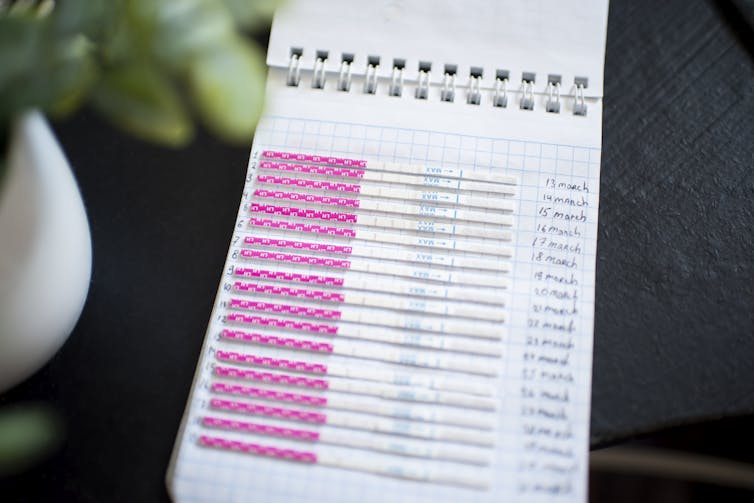

Most Catholics dealing with infertility, however, find themselves in mainstream clinical settings that offer IVF. Women I interviewed who opted for IVF were frank in their critiques of church teachings and their skepticism of Catholic clinics. Many took issue with the underlying assumption that the people who ought to be procreating are heterosexual, married couples and that conception is usually possible without the help of IVF.

However, many of these women were also dissatisfied with the approach that mainstream clinics take. Some felt that those clinics were focused on profit – a concern shared by some scholars scrutinizing the fertility industry. Some women also felt pressured to genetically test their embryos for chromosomal abnormalities and to discard unused embryos, even after explaining to staff that destroying them would be out of step with their moral commitments.

Understanding patient experiences in either kind of clinic helps underscore the difficulties many people face navigating infertility – and the stakes of policy reform.

The Trump administration’s plan largely maintains the status quo for IVF access while making more room for alternative treatments. But it intensifies questions about how the government responds to religious beliefs about reproductive health care, especially disagreements about the moral status of embryos. For now, patients and providers will continue to navigate a fractured landscape.

![]()

Emma Kennedy is affiliated with the Center for Genetics and Society.

– ref. How a niche Catholic approach to infertility treatment became a new talking point for MAHA conservatives – https://theconversation.com/how-a-niche-catholic-approach-to-infertility-treatment-became-a-new-talking-point-for-maha-conservatives-265461