Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By Florent Montaclair, Enseignant Université, Université Marie et Louis Pasteur (UMLP)

Dans le sillage de la Révolution de 1789, la France connaît, au cours du XIXe siècle, de nombreuses péripéties politiques. Loin de l’image de l’artiste enfermé dans ses appartements, penché uniquement sur ses textes littéraires, des écrivains et écrivaines de l’époque s’engagent dans les débats politiques de leur temps.

En 1836, avec la parution des premiers romans-feuilletons en France dans les journaux quotidiens, l’écrivain devient une figure non plus seulement des salons, mais aussi de la société : il est reconnu dans la rue, il est invité par les rois, il « influence » l’opinion des lecteurs. Avec des tirages, sous le Second Empire, qui passent, tous titres confondus, de 200 000 exemplaires par jour à 1,5 million, le feuilleton est lu, relu, prêté, discuté par les maîtres, leurs enfants, les domestiques et les concierges, pour reprendre les termes d’un feuilletoniste oublié, Louis Reybaud.

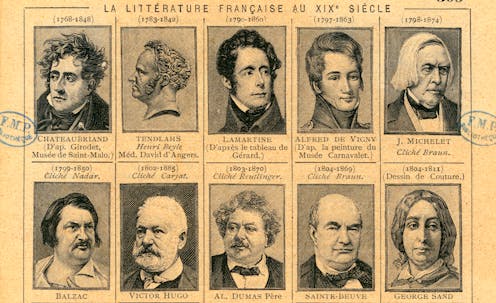

L’écrivain du XIXe siècle appartient majoritairement à la bourgeoisie : il est de formation initiale en médecine (Eugène Sue, Paul Féval), en droit ou comptabilité (Gustave Flaubert, Jules Verne, Guy de Maupassant, Edmond de Goncourt), il est officier ou fils de généraux (Alphonse de Lamartine, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo)… À noter un cas particulier, George Sand qui descend à la fois du maréchal de Saxe par son père et et d’un tenancier de billard par sa mère.

On voit bien l’articulation entre ces professions et les réflexions sociales, politiques ou institutionnelles : par leur métier initial, les écrivains s’intéressent à la défense de la nation (militaires), à la santé de leurs concitoyens (médecins), à l’organisation administrative de l’état (notaires, juristes). Devenus célèbres, certains auteurs briguent même les suffrages de leurs concitoyens : la députation (Dumas, Lamartine, Hugo), les ministères (Tocqueville, Gobineau, Stahl), le Sénat (Hugo), les conseils généraux ou municipaux (Gobineau, Verne, Lamartine).

La grande question politique qui préoccupe alors ces écrivains, tant dans les instances où ils sont élus que dans leurs œuvres, est celle de la réunification du corps social : comment sortir d’un cycle révolutionnaire, né en 1789, qui provoque durant tout le siècle émeutes et chutes de régimes ? Comment en somme bonifier l’héritage révolutionnaire en créant une nation apaisée ?

« Guérir » les maux de la société

Prise de la Bastille en 1789, chute de Charles X en 1830, émeutes de 1832, chute de Louis-Philippe en février 1848, émeutes de juin 1848, Commune en 1871, la violence politique contre les hommes, les biens, les institutions et les symboles est récurrente tout au long du XIXe siècle.

Comment sortir de la violence ? Les écrivains exploreront plusieurs solutions qui leur paraissent pouvoir « guérir » les maux de la société.

À partir de la Commission du Luxembourg (28 février -16 mai 1848) réunie au Sénat par Lamartine, alors chef du gouvernement provisoire de la Deuxième République, pour déterminer quelle sera la politique économique de la République, trois voies se dessinent pour sortir le peuple de la misère et le faire entrer dans une communauté d’intérêts avec la classe moyenne et supérieure.

Le philosophe et député Pierre-Joseph Proudhon défend le développement d’une France de la coopérative, regroupant les travailleurs dans des microentreprises dont ils seraient les ouvriers et les patrons. Notamment défendue par Victor Hugo dans « Les Misérables », cette idée s’effondre à l’Assemblée lorsqu’il s’agit de proposer un financement de ces coopératives par l’État pour acheter en fond de départ le matériel et les machines, par exemple. L’impôt sur le revenu voulu par le député Proudhon est vu par les députés comme contraire aux droits de l’homme et du citoyen : la propriété est considérée sacrée.

À lire aussi :

Littérature française : pourquoi les autrices sont-elles encore reléguées au second plan ?

Louis Reybaud et l’Académie des sciences morales et politiques défendent la suppression des frontières, la diminution des taxes, la limitation du nombre des fonctionnaires et la constitution de grandes fortunes, ce qui mécaniquement augmente les salaires. Ces idées sont rejetées, à un moment où l’idée centrale de l’État est de construire une nation et non pas de l’ouvrir sur le monde.

Lamartine met finalement en place, sur les conseils du ministre Louis Blanc, un contrôle de l’économie par l’État avec un droit du travail et la création d’ateliers nationaux qui fournissent des emplois aux ouvriers sans activités. Opposé à cette idée, Hugo déclare à la Chambre : « La monarchie avait les oisifs, la République aura les fainéants » : penser que l’État peut payer des cent mille travailleurs est perçu comme la création d’un assistanat généralisé.

La fermeture de ces ateliers qui n’arrivaient pas à trouver du travail à tous les chômeurs en juin 1848 provoque des émeutes : le peuple parisien pensait que l’idée était bonne et refuse de se disperser. Les combats avec l’armée font 15 000 tués ou blessés dans les rues de Paris.

Du lundi au vendredi + le dimanche, recevez gratuitement les analyses et décryptages de nos experts pour un autre regard sur l’actualité. Abonnez-vous dès aujourd’hui !

Le mépris du peuple

La violence populaire trouve-t-elle son origine dans l’organisation du régime ? Tous les écrivains le pensent, et adhèrent, par une sorte de pensée magique, à une république idéale. Ils soutiennent donc à l’unanimité la révolution de février 1848 qui fait tomber la Monarchie parlementaire de Louis-Philippe, et se réjouissent de l’abdication de Napoléon III en 1870 qui crée la IIIe République.

Mais comment expliquer alors que quelques mois plus tard, en juillet 1848 puis en avril 1871, le peuple en arme se soulève contre la république ? Désemparés, les écrivains, à l’exception de Jules Vallès, passeront de la vision d’un peuple héroïque à un peuple dénaturé : les écrivains rejettent la possibilité de se révolter contre une république. « Nous ne dirons rien de leurs femelles par respect pour les femmes, à qui elles ressemblent quand elles sont mortes », lâche Alexandre Dumas-fils, « une stupide et cruelle brute ! » ajoute Joris-Karl Huysmans pour qualifier le peuple. Leconte de Lisle écrit à la poète José-Maria de Heredia : « La Commune ? Ce fut la ligue de tous les déclassés, de tous les incapables, de tous les envieux, de tous les assassins, de tous les voleurs, mauvais poètes, mauvais peintres, journalistes manqués, tenanciers de bas étage ». Et Alphonse Daudet conclut : « Des têtes de pions, collets crasseux, cheveux luisants, les toqués, les éleveurs d’escargots, les sauveurs du peuple, les déclassés, les tristes, les traînards, les incapables ; pourquoi les ouvriers se sont-ils mêlés de politique ? »

Wikicommons

L’idée que le peuple, pauvre et inculte, puisse être le grand décideur de l’avenir de l’État heurte les consciences bourgeoises. Alexandre Dumas écrit d’ailleurs : « Ce qui fait l’avenir de la République, c’est justement ceci, qu’il lui reste beaucoup à faire dans l’avenir. Laissez-la donc d’abord être République bourgeoise ; puis, avec l’aide des années, elle deviendra République démocratique ; puis, avec l’aide des siècles, elle deviendra République sociale. »

Les écrivains qui soutinrent ouvertement les révoltes du peuple sont peu nombreux : le philosophe Pierre-Joseph Proudhon et le romancier Jules Vallès. Reste cependant une forme de bienveillance chez certains comme les Frères Goncourt qui se diront soulagés lorsque les exécutions de communards cessèrent ou Victor Hugo qui sera le premier à demander la grâce des émeutiers.

Le peuple devra encore attendre

Selon Jules Michelet, historien et professeur au Collège de France, le peuple est « barbare » parce qu’il est muet (sans droit de vote) et « enfant » car sans instruction, donc sans pensée claire. Mais la plupart des écrivains rejettent l’obligation à l’État de donner un suffrage universel et une instruction gratuite. « Quant au bon peuple, l’instruction « gratuite et obligatoire » l’achèvera » écrit Flaubert et « L’instruction gratuite et obligatoire n’y fera rien qu’augmenter le nombre des imbéciles. Le plus pressé est d’instruire les riches qui, en somme, sont les plus forts. »

En espérant donc que le peuple s’élève dans la richesse pour participer aux votes censitaires et dans l’éducation pour participer au monde des idées, il faut attendre pour lui donner la possibilité de la parole et des droits.

« Peuple, encore une fois, nous te demandons la patience !… » déclare Proudhon dans son « Manifeste du peuple » ; « La patience est faite d’espérance » écrit Hugo dans « Claude Gueux ») ; « s’enrégimenter tranquillement, se connaître, se réunir en syndicats, lorsque les lois le permettraient ; puis, le matin où l’on se sentirait les coudes, où l’on se trouverait des millions de travailleurs en face de quelques milliers de fainéants, prendre le pouvoir, être les maîtres. Ah ! quel réveil de vérité et de justice ! » programme Zola dans « Germinal » et « Le Comte de Monte-Cristo », comme un clin d’œil à l’époque, se termine par ces mots : « Attendre et espérer ».

![]()

Florent Montaclair ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Comment les écrivains du XIXᵉ siècle se sont engagés dans les débats politiques de leur temps – https://theconversation.com/comment-les-ecrivains-du-xix-siecle-se-sont-engages-dans-les-debats-politiques-de-leur-temps-254649