Source: The Conversation – UK – By Filippo Menga, Visiting Research Fellow, Professor of Geography, University of Reading

Hosepipe bans have been announced in parts of England this summer. Following the driest spring in over a century, the Environment Agency has issued a medium drought risk warning, and Yorkshire Water will introduce restrictions starting Friday, 11 July. It’s a familiar story: reduced rainfall, shrinking reservoirs and renewed calls for restraint: take shorter showers, avoid watering the lawn, turn off the tap while brushing your teeth.

These appeals to personal responsibility reflect a broader way of thinking about water: that everyone, everywhere, is facing the same crisis, and that small individual actions are a meaningful response. But what if this narrative, familiar as it is, obscures more than it reveals?

In my new book, Thirst: The global quest to solve the water crisis, I argue that the phrase “global water crisis” may do more harm than good. It simplifies a complex global reality, collapsing vastly different situations into one seemingly shared emergency. While it evokes urgency, it conceals the very things that matter: the causes, politics and power dynamics that determine who gets water and who doesn’t.

What we call a single crisis is, in fact, many distinct ones. To see this clearly, we must move beyond the rhetoric of global scarcity and look closely at how drought plays out in different places. Consider the UK, the Horn of Africa, and Chile: three regions facing water stress in radically different ways.

UK: a crisis of infrastructure

Drought in the UK is rarely the result of absolute water scarcity. The country receives relatively consistent rainfall throughout the year. Even when droughts occur, the underlying issue is how water is managed, distributed and maintained.

Roughly a fifth of treated water is lost through leaking pipes, some of them over a century old. At the same time, privatised water companies have come under growing scrutiny for failing to invest in infrastructure while paying billions in dividends to shareholders. So calls for households to use less water often strike a dissonant note.

The UK’s droughts are not just the product of climate variability. They are also shaped by policy decisions, regulatory failures and eroding public trust. Temporary scarcity becomes a recurring crisis due to the structures meant to manage it.

Horn of Africa: survival and structural vulnerability

In the Horn of Africa, drought is catastrophic. Since 2020, the region has endured five consecutive failed rainy seasons – the worst in four decades. More than 30 million people across Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya face food insecurity. Livelihoods have collapsed and millions of people have been displaced.

Climate change is a driver, but so is politics. Armed conflict, weak governance and decades of underinvestment have left communities dangerously exposed. These vulnerabilities are rooted in longer histories of colonial exploitation and, more recently, the privatisation of essential services.

Adaptation refers to how communities try to cope with changing climate conditions using the resources they have. Local efforts to adapt to drought (such as digging new wells, planting drought-resistant crop or rationing limited supplies) are often informal or underfunded.

When prolonged droughts strike in places already facing poverty, conflict or weak governance, these coping strategies are rarely enough. Framing climate-induced drought as just another chapter in a global water crisis erases the specific conditions that make it so deadly.

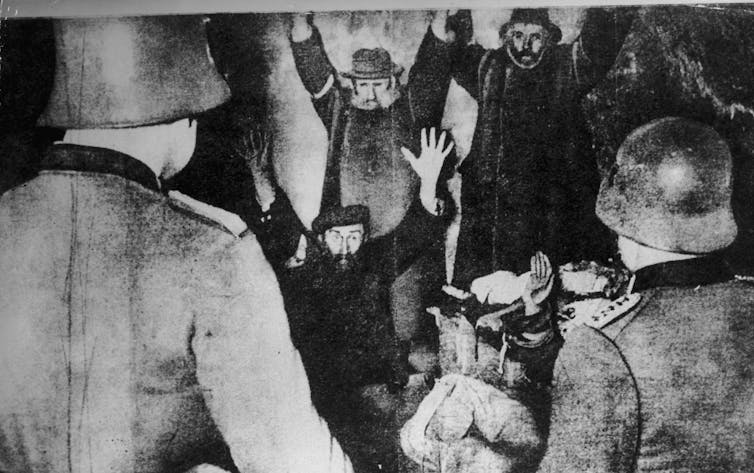

Dieter Telemans/Panos Pictures, CC BY-NC-ND

Chile: extraction and exclusion

Chile’s water crisis is often linked to drought. But the underlying issue is extraction. The country holds over half of the world’s lithium reserves, a metal critical to electric vehicles and energy storage.

Lithium is mined through an intensely water-consuming process in the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, often on Indigenous land. Communities have seen water tables drop and wetlands disappear while receiving little benefit.

Chile’s water laws, introduced under the Pinochet regime, allow private companies to hold long-term rights regardless of environmental or social cost. Here, water scarcity is driven less by rainfall and more by law, ownership and global demand for renewable technologies. Framing Chile’s situation as just another example of a global water crisis overlooks the deeper political and economic forces that shape how water is managed – and who gets to benefit from it.

No single crisis, no single solution

While drought is intensifying, its causes and consequences vary. In the UK, it’s about infrastructure and governance. In the Horn of Africa, it’s about historical injustice and systemic neglect. In Chile, it’s about legal frameworks and resource extraction.

Labelling this simply as a global water crisis oversimplifies the issue and steers attention away from the root causes. It promotes technical solutions while ignoring the political questions of who has access to water and who controls it.

This approach often favours private companies and international organisations, sidelining local communities and institutions. Instead of holding power to account, it risks shifting responsibility without making meaningful changes to how power and resources are shared.

In Thirst, I argue that the crisis of water is a cultural and political one. Who controls water, who profits from it, who bears the cost of its depletion: these are the defining questions of our time. And they cannot be answered with generalities. We don’t need one big solution. We need many small, just ones.

This article features a reference to a book that has been included for editorial reasons. If you click on one of the links to bookshop.org and go on to buy something, The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Filippo Menga does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Three types of drought – and why there’s no such thing as a global water crisis – https://theconversation.com/three-types-of-drought-and-why-theres-no-such-thing-as-a-global-water-crisis-260723