Source: The Conversation – USA – By Julie Phillippi, Associate Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery and Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Why is heart cancer so rare? – Jackson, age 12, Davis, California

You probably know someone who is affected by cancer. This disease results when cells divide uncontrollably and can make a person sick, sometimes very seriously.

Cancer can occur anywhere in the body because every tissue and organ is made up of billions or even trillions of cells. But there are some parts of the body where cancer doesn’t happen as often, such as the heart. Studies show 3 in 10,000 people develop heart cancer. In comparison, 1 in 20 women are expected to develop breast cancer. Why is that?

I’m a biologist who specializes in the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. A big part of my work focuses on how cells interact with their environment to regulate the function of tissues and organs. Disease can develop when things go wrong.

Turns out, heart cells have unique features that make them super resistant to cancer.

How cancer starts

Cells produce more cells to grow, replace older or worn-out cells or to repair damaged tissues. This process is called cell division. Each type of cell in the body divides at different rates based on multiple factors, including what their function is and a person’s age.

For example, the cells of a growing human embryo divide extremely fast, undergoing four divisions in three days. The cells that make up the skin, nails and hair regularly replenish across your lifespan. Bone cells divide at a rate that will give you an entirely new skeleton approximately every 10 years.

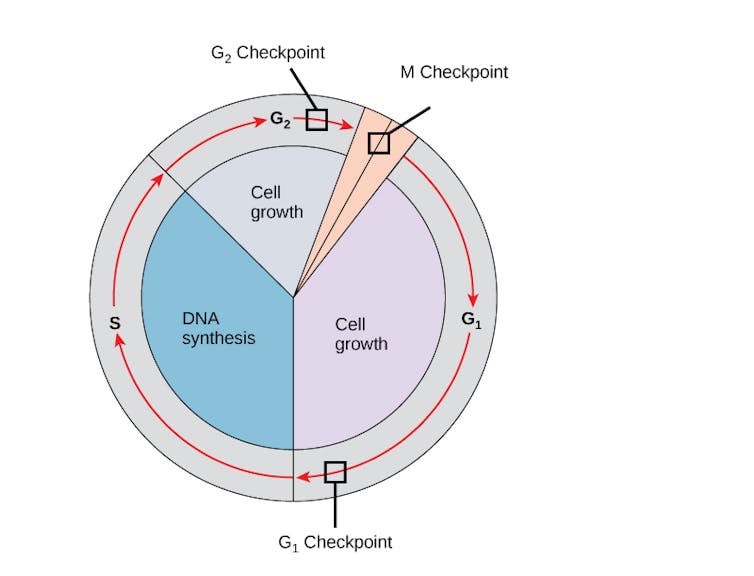

Whether and how often a cell divides is tightly regulated by a series of molecular checkpoints. During cell division, genes within DNA are duplicated and evenly distributed into two daughter cells. Damage to these genes caused by exposure to harmful chemicals, ultraviolet light or radiation can result in mutations that cause disease. Mutations can just happen randomly, too. When there are mutations on the genes regulating cell division, cancer can develop.

OpenStax, CC BY-SA

What protects heart cells from cancer?

Even though the heart is the first organ to form and start working during early development, cells in the adult heart divide very few times after birth, with division dramatically declining after age 20. In fact, less than 50% of heart cells are replaced over the course of an average human life. That means half of the heart cells you’re born with will be helping pump blood for your entire life.

This low rate of cell division in the adult heart likely serves as its primary defense against cancer. The less often a cell divides, the fewer opportunities there are for mistakes during DNA replication.

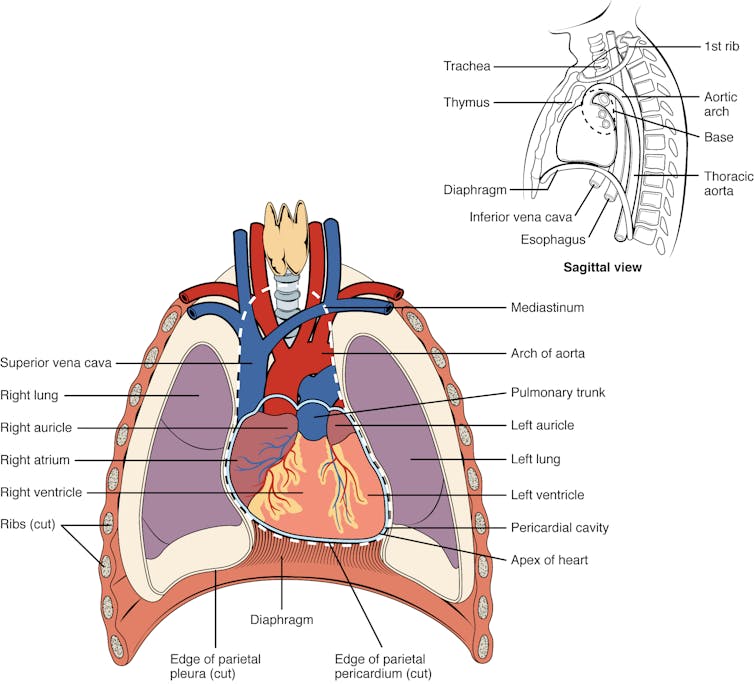

OpenStax, CC BY-SA

The heart is also less directly exposed to cancer-causing factors, such as UV light on the skin or inhaled substances in the lung, due to its protected location in the chest.

Unfortunately, the heart’s low rate of cell division has some downsides, such as a reduced ability to repair and replace cells damaged by disease, injury or aging.

Why heart cancer still happens

Even with the heart’s resistance to cancer, tumors may still form.

When cancer is found in the heart, it’s often the result of cancer cells migrating from another part of the body to the heart. This process is called metastasis. Certain types of skin cancers or cancers in the chest are more likely to spread to the heart, though this is still rare.

When they do happen, heart tumors can be quite serious and more aggressive than other cancers. A study analyzing more than 100,000 heart cancer cases in the United States found that patients who underwent surgery and chemotherapy to treat their heart cancer survived longer than those who did not.

Successful cancer care spans multiple areas of medicine. These include palliative care, which focuses on relieving pain and addressing symptoms, and integrative medicine, which considers the mind-body-spirit connection.

Heart cancer holds clues to heart regeneration

Understanding how heart cells divide and what causes that process to change offers clues about disease and shapes ideas for new treatments.

For example, research into how heart cells divide helps scientists better understand why the heart doesn’t heal well after a heart attack. Researchers found that although failing hearts have more dividing cells than healthy hearts, they need help to recover fully.

New technologies, such as the ability to reprogram blood cells into heart cells, have allowed researchers to develop new heart disease models to study and one day achieve heart regeneration. This opens doors for new treatments for heart diseases, including cancer.

Understanding why cancer doesn’t happen is just as important for developing new and better treatments as knowing why it does. The answers to both questions lie truly at the heart.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

![]()

Julie Phillippi receives funding from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

– ref. Why is heart cancer so rare? A biologist explains – https://theconversation.com/why-is-heart-cancer-so-rare-a-biologist-explains-256055