Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Ray Laurence, Professor of Ancient History, Macquarie University

At its height, the Roman empire covered some 5 million square kilometres and was home to around 60 million people. This vast territory and huge population were held together via a network of long-distance roads connecting places hundreds and even thousands of kilometres apart.

Compared with a modern road, a Roman road was in many ways over-engineered. Layers of material often extended a metre or two into the ground beneath the surface, and in Italy roads were paved with volcanic rock or limestone.

Roads were also furnished with milestones bearing distance measurements. These would help calculate how long a journey might take or the time for a letter to reach a person elsewhere.

Thanks to these long-lasting archaeological remnants, as well as written records, we can build a picture of what the road network looked like thousands of years ago.

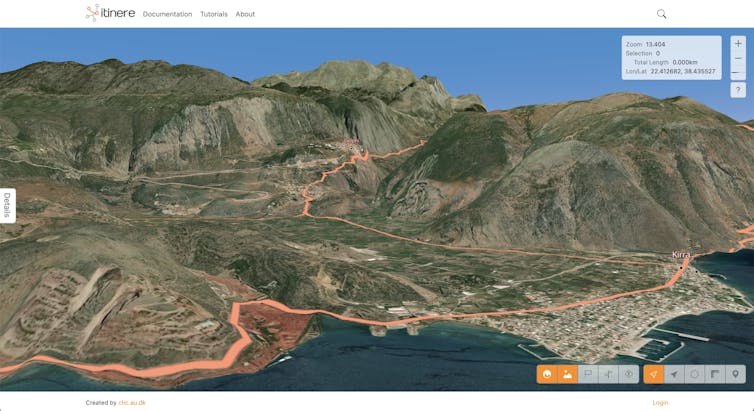

A new, comprehensive map and digital dataset published by a team of researchers led by Tom Brughmans at Aarhus University in Denmark shows almost 300,000 kilometres of roads spanning an area of close to 4 million square kilometres.

Itiner-e, CC BY

The road network

The Itiner-e dataset was pieced together from archaeological and historical records, topographic maps, and satellite imagery.

It represents a substantial 59% increase over the previous mapping of 188,555 kilometres of Roman roads. This is a very significant expansion of our mapped knowledge of ancient infrastructure.

LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BY

About one-third of the 14,769 defined road sections in the dataset are classified as long-distance main roads (such as the famous Via Appia that links Rome to southern Italy). The other two-thirds are secondary roads, mostly with no known name.

The researchers have been transparent about the reliability of their data. Only 2.7% of the mapped roads have precisely known locations, while 89.8% are less precisely known and 7.4% represent hypothesised routes based on available evidence.

More realistic roads – but detail still lacking

Itiner-e has improved on past efforts with improved coverage of roads in the Iberian Peninsula, Greece and North Africa, as well as a crucial methodological refinement in how routes are mapped.

Rather than imposing idealised straight lines, the researchers adapted previously proposed routes to fit geographical realities. This means mountain roads can follow winding, practical paths, for example.

Itiner-e, CC BY

Although there is a considerable increase in the data for Roman roads in this mapping, it does not include all the available data for the existence of Roman roads. Looking at the hinterland of Rome, for example, I found great attention to the major roads and secondary roads but no attempt to map the smaller local networks of roads that have come to light in field surveys over the past century.

Itiner-e has great strength as a map of the big picture, but it also points to a need to create localised maps with greater detail. These could use our knowledge of the transport infrastructure of specific cities.

There is much published archaeological evidence that is yet to be incorporated into a digital platform and map to make it available to a wider academic constituency.

Travel time in the Roman empire

Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BY

Itiner-e’s map also incorporates key elements from Stanford University’s Orbis interface, which calculates the time it would have taken to travel from point A to B in the ancient world.

The basis for travel by road is assumed to have been humans walking (4km per hour), ox carts (2km per hour), pack animals (4.5km per hour) and horse courier (6km per hour).

This is fine, but it leaves out mule-drawn carriages, which were the major form of passenger travel. Mules have greater strength and endurance than horses, and became the preferred motive power in the Roman empire.

What next?

Itiner-e provides a new means to investigate Roman transportation. We can relate the map to the presence of known cities, and begin to understand the nature of the transport network in supporting the lives of the people who lived in them.

This opens new avenues of inquiry as well. With the network of roads defined, we might be able to estimate the number of animals such as mules, donkeys, oxen and horses required to support a system of communication.

For example, how many journeys were required to communicate the death of an emperor (often not in Rome but in one of the provinces) to all parts of the empire?

Some inscriptions refer to specifically dated renewal of sections of the network of roads, due to the collapse of bridges and so on. It may be possible to investigate the effect of such a collapse of a section of the road network using Itiner-e.

These and many other questions remain to be answered.

![]()

Ray Laurence does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The Roman empire built 300,000 kilometres of roads: new study – https://theconversation.com/the-roman-empire-built-300-000-kilometres-of-roads-new-study-269186